As the November elections in the US draw near, John Bloom examines the culture of untruth that has increasingly become the norm.

Making sense of national politics in the United States has been crazy-making and compelling at the same time. There are so many layers of fact and fiction. The overshadowing spectacle of the campaigning seems so transparently and somewhat unbearably about power, money, the rule of personality, national identity, the role of government, and the loss of any nuance in the US’s relationships with the rest of our interdependent world. Personally, as an enterprise owner, a trustee on boards of tax-exempt charities, a taxpayer, a recipient of Social Security, an advisor to organizations, and a grandparent, whatever transpires through the current spectacle matters tremendously. The compelling need to find and experience a semblance of truth in the context of the crazy-making requires individual perseverance, an openness to others’ perceptions, and a co-created moral compass to navigate the social field of post-truth America [US].

Much of the political rhetoric uses freedom as a banner, but truth and freedom are inextricably linked. The passage from the John Gospel [8:32] keeps sounding for me: “Ye shall know the truth; and the truth shall make you free.” If the truth shall make you free, what does an untruth do? What are the consequences of repeated and unchallenged untruths? Further in the John Gospel [8:34], Jesus makes an important distinction between physical enslavement of others (“power over”) and metaphysical or inner enslavement created out of oneself: “and truly I say to you, everyone who commits sin is a slave of sin.” An untruth creates a kind of imprisonment—the very opposite of being free.

So how might a moral compass look, feel, and operate? Rudolf Steiner articulated a foundation for this in his Threefold Commonwealth (1917). This Commonwealth was his imagination for the social world, mirroring the moral imagination of the threefold human being in thinking, feeling, and willing. By extension, a social ethic would emerge co-created by ethical individuals. Such a framework places each of us inescapably within the threefold, and serves as a roadmap for responsibly re-righting a social field which is now essentially untethered from any moral ground. In essence, the public social field is currently operating with systemic untruth. How can we cultivate an attitude of soul, a moral compass, that guides our actions and our society toward rightness, fairness, and sufficiency—freedom in spirit, equality in the dispensation of justice, and compassionate interdependence in the economy?

Spiritual and Political Freedom

If one observes the linguistic currents of national and regional politics in the United States, freedom—the word, the concept, and its ethos—is a central battleground for power and control of government, and the hearts and minds of the citizens. However, spiritual freedom and political freedom have been conflated, mischaracterized, and deeply misunderstood. Freedom, spiritual or political, is precious and hard-won, whether via an individual journey or a political revolution. Further, it is not easy to move beyond personal freedom into a social space that recognizes each other’s inner freedom, making it possible to co-create agreements out of real equality, person-to-person. As a culture, we are far from equality in our socio-political practices, even if the concept resides in our ideals. Inequity in the exercise of rights remains. Ideology, money, and its associated power have made it so.

So long as self-interest remains the driving force in economic activity, we live with another untruth embodied in the thought-statement: I need to work to meet my own needs. An advertisement for a graduate business program in the New York Times read, “Earn What You Are Worth!” Buried in this statement are the assumptions that we work for ourselves, that our value as a human being is measured by what we earn, and that education is a commodity. All commercial advertising propagates the illusion that the consumer world is organized primarily to meet personal wants and needs. The reality is that we work to meet others’ needs, and through that work, our needs are met—it is a social imagination in which true interdependence becomes visible.

The Abyss of Untruth

In short, our current paradigm is operating on untruths—cultural, rights, and economic. The adversarial forces, through the media and cultural channels, have promulgated the “lie” as a belief system or ideology, which then governs what we perceive or think we perceive. Beliefs overshadow facts and evidence and override free knowing. The old adage, “I’ll believe it when I see it,” no longer holds. Instead, we have “I’ll see it when I believe it.”

The task is to make sense of the chasm of untruth, the abyss that sits between moral truth and the self-serving narratives that have been amplified through the media and absorbed by some portion of the population. An emblem of this absorption is a sign carried by protestors (easily found on the web) that states: “Tell the [US] government to keep its hands off my Medicare!” Fact: Medicare is a government healthcare program. So, how do we navigate in a world where post-truth statements are woven into whole narratives, adopted as beliefs, and publicly advocated?

The chasm has been made deeper as the tools of media have been weaponized. The current usage of phrases like: “the deep state,” “deepfakes,” and “gaslighting,” are all constructs designed to make us doubt what we know and establish that only certain people know more. These techniques and others set the foundation for the proposition that we are now victims of the “deep state” and in need of being rescued—and in need of a self-identified rescuer.

Deception of Perception

The current situation in the United States and the way that fabricated narratives can be generated and distributed with such facility is a result of technological systems of representation that have evolved in the US and Western culture over a long time. The glory of European Renaissance artists gave us two- and three-point perspectives and the imperative of representation serving the optical illusion of reality. This representational imperative developed through the advent of photography and film to what is now called virtual reality—becoming more disconnected from the physical source each step along the way. It is driven by the notion that the human perceptual system can be stimulated with an illusion of reality so convincing that, without training, one is unable to distinguish the real from the simulacrum.

Add to this pictorial-based framework the more linguistic framework of artificial intelligence, which is, to a degree, the aggregate of the history of human thought and expression digitized, recycled, recombined, upcycled, and downloadable. When the pictorial and linguistic systems are unified, human senses can be triggered into a real-time-real-space modality. The genius is undeniable, but the ersatz experience is anything but neutral. A part of consciousness that recognizes self-authorship of experience in real-time is put in abeyance.

The untruth here is that appearance is the equivalent to what is represented, the ersatz replaces the substantive, and—here is the crux—the untruth becomes the norm. This is the turning through which we enslave ourselves—the sin to which Jesus refers. With the advent of the replacement, “truth” becomes malleable, becomes post-truth.

Perspective systems marked an advancement in Western human consciousness. That impulse has now been co-opted into techniques for conditioning our perceptual system and shaping a sense of self, all according to someone else’s agenda or “program.” We live with virtual reality and the products of artificial intelligence as fascinating experiential and cultural untruths. Social media have made it easy to breach shared ethical and moral bounds—and bounds shared by whom? Having a conversation about all this is difficult because the language of experience and ethical frameworks is stuck in the chasm between evidence and belief.

The Survival of Truth and Freedom

Resisting the oppression of a system built on untruths is challenging because the truth—the social reality of economic, ecological, and divided culture—is hard to bear. But adversity and a Michaelic attitude are motivators to overcome dominant untruths that currently seem to define and separate us. As a release from spiritual imprisonment, “the truth shall make us free.” But we had better be prepared with our moral compasses in hand to lead by example.

There is one matter that still needs mindfulness in approaching these issues of the ersatz and post-truth. It has to do with evidence and an anthroposophical worldview. A generous materialist or skeptic might at least grant that such a thing as the spiritual world is possible given that there is no evidence to the contrary. A less generous and more adversarial view would trash any talk of the spiritual world as a fabrication or, worse, a lie. This is the harshest of materialistic judgments and arises from belief systems that centralize power out of fear, that only acknowledge certain people’s access to the spiritual, and that want to maintain power over the spiritual world through doctrine. Thus, anyone who tells you that you cannot think your own thoughts or experience your own experiences does not want to understand truth and freedom in the deepest sense of the words.

As the political battle cries are sounded, billions of dollars are being expended on convincing hearts and minds of the righteous and the evil. Truth and freedom need loving care in order to survive the onslaught. They are fundamental to a moral compass. The bridge between political reality and individual beliefs is the capacity for relationships that see beyond the untruthful, recognize the inner freedom of another, and work toward new and tenable agreements with an awareness of our actual economic interdependence. Warmth is a counterforce to division and separation. The reality is, we are going to need each other no matter our politics or truths. Actually, we always did.

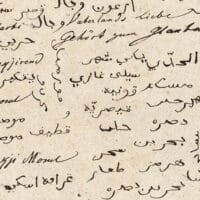

Image Jasper Johns Flag at Museum of Modern Art New York, Picture: Esther Westerfeld. CC BY 2.0.