The Harden-Eulenburg affair caused quite a stir at the beginning of the twentieth century. Rudolf Steiner was acquainted with the protagonists, both of whom ended their lives in sorrow.

In the years 1906 to 1908, the German Empire was shocked by a scandal known as the Harden-Eulenburg affair. The original cause was that, in the view of Bismarck’s admirer Maximilian Harden (1861–1927), publicist and editor of the influential weekly journal Zukunft [Future], Kaiser Wilhelm II was acting too compliantly in international politics. For example, he criticized Wilhelm II for a diplomatic defeat in the so-called Morocco crisis of 1905/06, which concerned whether France should continue to maintain the protectorate over Morocco. In this context, Harden had advocated a “preventive war” against France. That it didn’t come to this, the journalist attributed to the “exaggerated love of peace”1 of the “Liebenberg Circle,” which had formed around the sensitive and musically talented diplomat, Philipp, Prince of Eulenburg, and which the Kaiser sometimes also joined. This circle of high-ranking men occasionally met at Prince Eulenburg’s estate, Liebenberg Castle, in northern Brandenburg. Since Harden could not go after the monarch directly, he accused the circle of friends of negatively influencing German foreign policy in a series of articles in the journal Zukunft, following the Kaiser’s visit to Liebenberg in November 1906,2 and accused them of homosexual and spiritualist tendencies.3 When Wilhelm II found out about this in May 1907, he reacted immediately: He cast off his long-standing friends and demanded legal clarification of the allegations. A series of lawsuits began,4 and the matter became a huge topic in the press, which outdid itself in rumor-mongering. Thus, the “Liebenberg Round Table” was “said to have certainly influenced politics and all sorts of mystical, spiritualist nonsense, as well as other compromising things.”5

The downfall of Philipp von Eulenburg and his friends, as well as the lawsuits that dragged on for years, had a colossal impact on society and politics. Among other things, the military gained influence with the Kaiser, and the monarchy’s reputation faded. Livelihoods were destroyed—above all, that of the Prince of Eulenburg. Not only was he alleged to be homosexual (which was still considered a social stigma at the time), not only was he cast off by the Kaiser and many of his peers, but he was also accused of perjury. For, in November 1907, he swore in court under oath that he had never engaged in homosexual behavior—and was later confronted with two witnesses who claimed to have had such contacts with him. After a breakdown of health, the lawsuit was suspended against Prince Eulenburg’s will6 and brought to a conclusion. On April 30, 1908, he noted in his diary: “What a fate! I am slowly inuring myself to the idea that I am completely done for. How could it possibly be otherwise? I am being done down by false witnesses, Press, Government, Jewish gold. I see no hope of rescue. God!” And on May 5, 1908: “My reputation has been destroyed by the current attacks in the Press, and my family irretrievably and terribly injured. What can be done to improve the situation in any degree for them?”7

In his memoirs, the anthroposophical doctor Wilhelm zur Linden reported that Friedrich-Wend, Count of Eulenburg, came to see him in his practice in 1937 and asked him for advice “due to the still-unresolved consequences of the severe shocks he had suffered in the years 1905 to 1909 when they had tried to destroy his father . . . politically and personally, in order to hit the Kaiser and the monarchist idea.”8 Zur Linden said that, after many years, Friedrich-Wend von Eulenburg had met the sailor Jakob Ernst, who had made incriminating statements about Philipp von Eulenburg, and had greeted him: “The man had now rushed up to him and exclaimed: ‘What, you still greet me, when I acted like that towards your father? But, indeed, I couldn’t help it; the lawyer had said I’d go to jail if I didn’t!’”9

The ‘I’ that I would like to be

As it turns out, Rudolf Steiner, in different periods of his life, had personal relationships with both of the main protagonists of the affair—Prince Philipp von Eulenburg and Maximilian Harden.

Maximilian Harden—a former actor turned journalist—had met him through their collaborative friend Hans Olden shortly before the founding of the journal Zukunft. In July 1892, Rudolf Steiner published a detailed review of a collection of essays by Harden, which the latter had published under the pseudonym “Apostata.” At the time, he valued Harden as a “type of distinguished writer” who had respect for the reader and did not “[lack] that high sense of truth that is the characteristic of a distinguished human being. Whoever is true always speaks more or less paradoxically.” He was also—and this was especially appealing to Rudolf Steiner at the time—a “deifier of the individual” instead of worshiping the “principle.”10 Harden was deeply touched by the review and wrote to Rudolf Steiner on September 10, 1892: “Highly revered Sir, my dear friend Hans Olden was so kind as to send to me some essays of yours. One of them not only afforded me kindness but also spoke about the ‘I’ that I would like to be in an almost exhaustive and remarkably clear-sighted way. Both of these don’t happen to me often, and I can only sincerely thank you.” Enclosed with the letter was an invitation to collaborate on his journal project Zukunft, which he, as Harden says in his letter, is offering not on account of the positive review: “But, should I miss out on a fine thinker just because he happens to discover good sides in me? I heartily ask you for your kind collaboration.”11

In fact, Rudolf Steiner wrote the article, “Eine ‘Gesellschaft für ethische Kultur’” [A “Society for Ethical Culture”] for one of the first numbers of Zukunft, dated October 29, 1892, in which he opposed the “indulgence in the buttery ideals”12 of this newly founded association—ideals that lacked any basis in reality. The article brought Harden “a whole tidal wave of frank indignation.”13 It came to a fierce back and forth with articles and counter-articles, letters, and brochures, in which even Ernst Haeckel intervened, supporting Rudolf Steiner. Even though Maximilian Harden occasionally asked Rudolf Steiner for favors afterward—among other things, he used his literary knowledge for an article against the anti-Semitic agitator Hermann Ahlwardt—the relationship seemed to have cooled somewhat, and, after 1893, no further articles by the young Goethe scholar appeared in Zukunft.

In 1898, Rudolf Steiner, who had meanwhile become the editor of a magazine himself, wrote a scathing article against the editor of Zukunft in his Magazin für Litteratur [Magazine for Literature]: “Herr Harden als Kritiker: Eine Abrechnung” [Herr Harden as Critic: A Reckoning]. He had become an “offensive attacker,” a “pamphleteer.” The specific occasion for the article was Harden’s roasting of Hermann Sudermann’s play Johannes, which had deeply moved Rudolf Steiner. Harden, who was “excessively sensitive to the slightest criticism,”14 certainly took offense to this article. In early 1899, in a report on one of Harden’s conferences—a kind of literary chat before a recitation from Maeterlinck’s play Pelléas and Mélisande—Rudolf Steiner’s judgment was milder: “He has spoken many a good word. In many moments today, he reminded me of the time when I expected the very best from his great abilities for his future as a writer.” Journalism had “brought him down,” but he did not have to “strike a pose” because he was “strong enough to present himself.”15 The paths of the two crossed again when Harden published Elisabeth Förster-Nietzsche’s reply to Rudolf Steiner’s article, “Das Nietzsche-Archiv und seine Anklagen gegen den bisherigen Herausgeber” [The Nietzsche Archive and its accusations against the previous editor] in Zukunft on April 21, 1900. Rudolf Steiner asked for a corrigendum, which Harden promised since he held himself “obligated, not only legally,” to take this up.16 That was presumably the last direct contact between the two.

The Zukunft was becoming increasingly widespread and influential. Harden wrote tirelessly against the Kaiser—always trying to uncover scandals—and he didn’t spare his friends in the process.17 During the First World War, he was initially an enthusiastic supporter of the war but gradually “became a supporter of a policy of rapprochement.”18 He strongly expected to receive a leading political position after the war and was deeply disappointed when this did not occur. Maximilian Harden had enjoyed a long and intimate friendship with Walter Rathenau, who became foreign minister of Germany in February 1922, but this turned into a burning hatred. A few days after Rathenau’s assassination in June 1922, Harden was also the target of an attack by Freikorps members, in which he was seriously injured. A broken and embittered man, he solemnly renounced his Germanness due to the mild sentences given to the assassins and henceforth lived in Switzerland, where he died in 1927.

The extent to which Rudolf Steiner was involved with Harden is shown by the stately number of writings by and about the publicist in his library and occasional mentions in lectures.19 Also available are numerous copies, some with underlinings and annotations in his hand, from almost all volumes of the Zukunft, to which he subscribed.20

They Are Doing a True Labor of Love

By 1904 at the latest, Rudolf Steiner was also personally acquainted with Philipp von Eulenburg and some of his children.21 This acquaintance may have come about through the Moltke family, who were friends with both. Philipp, Prince of Eulenburg and Hertefeld (1847–1921) had studied law and obtained a doctorate after a short time in the military. In 1875, he married the Swedish Countess Augusta Sandels, with whom he had eight children, two of whom died in infancy. In 1886, he got to know Crown Prince Wilhelm II at a hunting party. A friendship soon developed between the two; Wilhelm admired the educated and urbane count. Von Eulenburg served as a diplomat at various courts and as ambassador in Vienna. It is said that he used his influence with the Kaiser in some important political decisions but never pushed for a leading position. In 1900, he was elevated to the rank of prince [Fürst]. He retired in 1902 for health reasons but remained an influential adviser to the Kaiser.

On September 10, 1905, Prince Eulenburg invited Rudolf Steiner to Liebenberg: “Dear Doctor, it is not only my own great wish but also the wish of all my family members to see you here among us! Would it be possible for you to make a short trip here?” Apparently, Rudolf Steiner accepted this invitation on December 26, 1905.22 At the end of 1906, the Eulenburg family experienced a severe crisis: On the one hand, Harden began the above-mentioned attacks on the Prince and his friends in November 1906. But along with this, the family was worried because their daughter Augusta (Lycki) was expecting a child by her father’s secretary, Edmund Jaroljmek,23 and wanted to marry him. The Prince strongly opposed the relationship. He turned to Rudolf Steiner for help in this situation and, after the latter agreed to meet him in his Berlin apartment for a conversation, the Prince wrote: “I am deeply touched by your kindness! You are doing a true work of love.” On December 30, 1906, he thanked him again: “Be assured that I will never forget the sacrifice with which you came to my aid in difficult hours!”24 The meeting probably took place on December 16, 1906, and shortly thereafter, there was a conversation between Rudolf Steiner and Augusta zu Eulenburg. She promised to go on a vacation to Switzerland with her family and to reconsider the marriage. But, on December 28, she had to “confess” to him in a letter from Baden near Vienna that she had not gone with the family after all: “You were so good and so understanding with me that I have to write to you about how it turned out.”25 She married Jaroljmek in London in February 1907 and initially lived with him in Florence.26

With the Kaiser distancing himself from Prince Eulenburg in May 1907, the Harden-Eulenburg affair gathered momentum, and the trials began. As the Liebenberg Circle was accused of having spiritualistic tendencies, Rudolf Steiner probably feared that the atmosphere in society could also turn against Theosophy. It is likely that this is what he was writing about to Marie von Sivers from Vienna on November 6, 1907—the same day that von Eulenburg testified under oath that the accusations against him were not true: “For it seems necessary to me, for reasons I have yet to tell you, that I could have a talk with Moltke right now. Recent events are creating a ghastly atmosphere against Theosophy . . . .”27

Philipp von Eulenburg withdrew into private life as a broken and sick man and died at Liebenberg Castle in 1921. There is no further evidence of contact with Rudolf Steiner. However, when Botho Sigwart von Eulenburg died of a bullet to the lung while serving at the front in 1915, he soon afterward established an after-death contact with his siblings.28 The sisters then turned to Rudolf Steiner. At first, they were not sure how to assess the communications they had received. Therefore, Marie von Eulenburg, Friedrich Wend’s wife, asked Steiner to meet for a conversation. They met in Berlin at the beginning of December 1915. She wrote about it to her siblings: “I was thus with Dr. Steiner for a full hour and a half—and the result made me deeply happy, for even though I know and no longer doubt; still I always feel as if I have to give thanks anew—it is proof, even if one needs no more proof in order to believe, and one can be happy about it. . . . It’s all true! and Steiner said that even many of the things he has dealt with in his various lectures were almost verbatim.”29

It is a tragic destiny that links the very different individualities of Philipp von Eulenburg and Maximilian Harden—but also quite remarkable that, at least in one moment in their lives, they both felt “seen” or understood by Rudolf Steiner.

Translation Joshua Kelberman

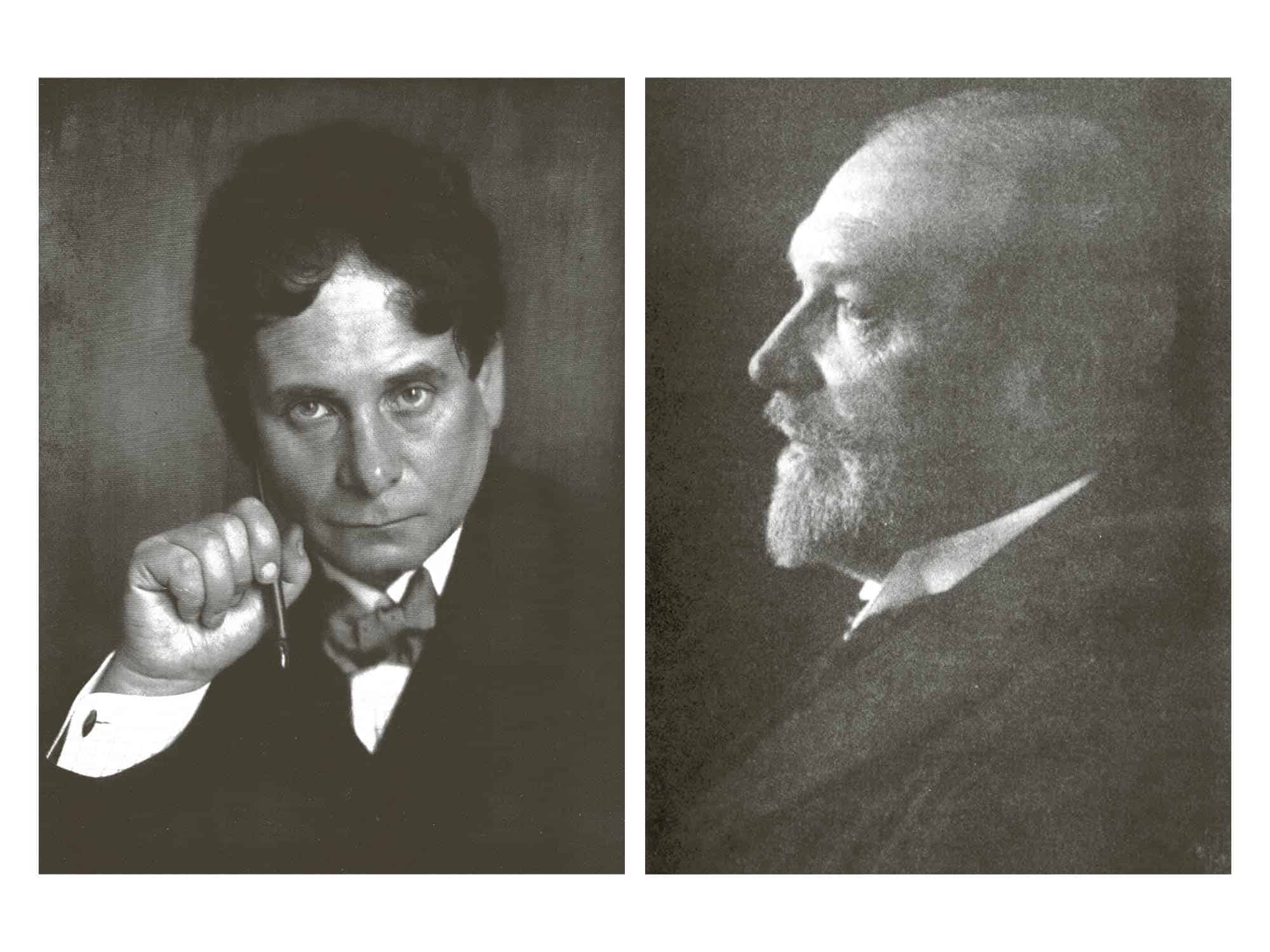

Title image Maximilian Harden, Philipp, Prince of Eulenburg-Hertefeld (around 1905), Source: Wikimedia

Footnotes

- Norman Domeier, The Eulenburg Affair: A Cultural History of Politics in the German Empire (New York: Camden House, 2015), 2.

- Already in 1890, the Circle and, specifically, the Prince of Eulenburg had supposedly already contributed to Bismarck’s abdication and “installed” the Imperial Chancellor Bernhard von Bülow. Concerning the Prince, Bismarck—in words according to Harden—said, “He was probably more concerned with all sorts of mysticism and ghosts than politics; he failed the diplomatic exam.” Maximilian Harden, Prozesse: Köpfe [Lawsuits: Chiefs], pt. 3 (Berlin: Erich Reiss, 1913), 170.

- Count Harry von Kessler, a friend of Harden, noted in his diary: “So the question is how far are you justified in using a prejudice that you don’t share to destroy a political opponent . . . .” Harry Graf Kessler, Journey to the Abyss: The Diaries of Count Harry Kessler, 1880-1918, translated by Laird Easton (New York: Random House, 2011), 425.

- The first lawsuit, which began in June 1907, concerned the military commander of Berlin, Kuno von Moltke, who had first challenged Harden to a duel and then reported him for defamation.

- Der Volksfreund [The people’s friend] (July 1, 1907). The circle was also accused of shielding the Kaiser from his advisors and the people.

- He declared: “I can and will continue to arbitrate. It is a shame that the doctors have declared themselves against my firm will. But, gentlemen, consider: an innocent man fights for his honor!” Peter Winzen, Das Ende der Kaiserherrlichkeit: Die Skandalprozesse um die homosexuellen Berater Wilhelms II. 1907–1909 [The end of imperial glory: The scandalous lawsuits of Wilhelm II’s homosexual advisors, 1907–1909] (Cologne, Weimar, Vienna: Böhlau, 2010), 293; cf. Peter Winzen, Homosexuality and Politics at the Court of Emperor Wilhelm II (BoD: Winzen, 2023).

- Johannes Haller, Philip Eulenburg: The Kaiser’s Friend, vol. 2, translated by Ethel Colburn Mayne (New York: Knopf, 1930), 228–29. He continued to consider his options—suicide, fleeing abroad, a stay in an asylum—but came to the conclusion that any of these would be seen as an admission of guilt and would not improve the situation of his family.

- Wilhelm zur Linden, Blick durchs Prisma: Lebensbericht eines Arztes [View through a prism: the life history of a doctor] (Frankfurt: Vittorio Klostermann, 1964), 47–49. After a thorough examination of the matter, zur Linden came to the conclusion that Philipp von Eulenburg had “through rash statements, incurred the hatred especially of the generals who surrounded the Kaiser” and that in this matter, the most diverse circles had joined forces in order to harm the Emperor: “Of 145 charges, only one remained in the end, and when this was nearly settled, the Prince, who had been brought to the courtroom on a stretcher with a feverish venous thrombosis, angina pectoris, and bronchitis, broke down shortly before the end of the trial. He was unconscious for almost an hour, and the doctors described it as life-threatening. The proceedings were then suspended, but his opponents were able to claim that there had been no acquittal. Unfortunately, the case was not reopened, and so the accusation of moral misconduct remained attached to the Prince.”

- See previous note, p. 50. Zur Linden adds: “The old servant and the head gardener Vogt (with whom I spoke about it) also expressed themselves to me in the same sense.” Johannes Haller quotes a letter of consolation from Jakob Ernst, written to the Prince on August 26, 1907, before he himself became involved in the matter: “You have never shown me or my family anything but kindness and never been the slightest trouble to any of us. Don’t be afraid—it will be all right. I made someone explain the paragraph to me—it is simply shocking to say such things about you. Such a normal healthy man as you are”; see footnote 7, p. 222.

- Maxilian Harden, Apostata, 2 vols. (Berlin: Georg Stilke, 1892); Rudolf Steiner, “Maximilian Harden ‘Apostata’,” Gesammelte Aufsätze zur Kultur- und Zeitgeschichte 1887–1901 [Collected Essays on Cultural and Contemporary History, 1887–1901], GA 31, 3rd edn. (Dornach: Rudolf Steiner Verlag, 1989), 158–162; first published in Literarischer Merkur [Literary Mercury] 12, no. 27, (July 2, 1892).

- Rudolf Steiner, Sämtliche Briefe [Collected Letters], vol. 2, GA 38/2 (Dornach: Rudolf Steiner Verlag, 2023), 412.

- See footnote 10, “Eine ‘Gesellschaft für ethische Kultur,’” 169–176; first published in Die Zukunft 1, no. 5 (October 29, 1892); cf. Rudolf Steiner, Human Evolution: A Spiritual-Scientific Quest, CW 183 (Forest Row, East Sussex: Rudolf Steiner Press, 2015), lecture in Dornach on August 26, 1918, where Rudolf Steiner later commented: “I don’t want to claim at all that, on purely logical grounds, my reasons against the ethicists were better than the reasons they put forward. But, the current catastrophe has, indeed, proceeded from all this buttery idealism.”

- See footnote 11, p. 428.

- Helga and Manfred Neumann, Maximilian Harden: Ein unerschrockener deutsch-jüdischer Kritiker und Publizist [A fearless German-Jewish critic and publicist] (Würzburg: Königshausen and Neumann, 2003), 18. This is also evident from the fact that he broke off his decades-long friendship with Hedwig Pringsheim because her son-in-law, Thomas Mann, did not want to write an appreciation for Harden’s sixtieth birthday.

- Rudolf Steiner, “Herr Harden als Kritiker: Eine Abrechnung,” Gesammelte Aufsätze zur Dramaturgie [Collected essays on dramaturgy], GA 29, 4th edn. (Basel: Rudolf Steiner Verlag, 2014), 324 f; first published in Magazin für Literatur 67, no. 13 (1898).

- Rudolf Steiner, Sämtliche Briefe [Collected Letters], vol. 3 (Basel: Rudolf Steiner Verlag, 2024), 230; see footnote 10, Rudolf Steiner, “Das Nietzsche-Archiv und seine Anklagen gegen den bisherigen Herausgeber” [The Nietzsche Archive and its accusations against the previous editor], 505–28; first published in Magazin für Literatur 69, no. 6, (Feb. 10, 1900).

- See Neumann and Neumann (footnote 14 above) for a good overview of the main topics of the Zukunft.

- See footnote 11, p. 15.

- Thus, for example, in the lecture of May 9, 1916, he opposed Harden’s, in his view, complete misunderstanding of Wilson, whom Harden called “America’s Fichte.” Rudolf Steiner, The Human Spirit Past and Present: Occult Fraternities and the Mystery of Golgotha (Forest Row, East Sussex: Rudolf Steiner Press, 2016), 176.

- For an overview, see Martina Maria Sam, ed., The Library of Rudolf Steiner, pt. 3 (Tiburon, CA: Chadwick Library Press, 2024), 1791–1793.

- In 1905, Philipp von Eulenburg’s children Karl (1885–1975) and Adine (1880–1957) corresponded with Rudolf Steiner about practices he had given them.

- This follows, on the one hand, from a dedication on this date by Eulenburg to Rudolf Steiner in his book Geistige Wege: Andachten eines Leidenden [Spiritual Paths: Devotions of a Sufferer], printed as a manuscript: “To Herr Dr. Steiner / most reverently / Philipp zu Eulenberg. / Liebenberg / 12.26.1905.” Martina Maria Sam, ed., The Library of Rudolf Steiner (LRS), B 112. A second dedication can be found in Eulenburg’s book, Eine Erinnerung an Graf Arthur Gobineau [A Remembrance of Count Arthur Gobineau] (Stuttgart: Fr. Frommann, 1906), LRS L 59. Furthermore, on December 31, 1905, Gerhard von Poellnitz (1876–1946) wrote to Rudolf Steiner asking him for to meet for a conversation: “As a guest at Liebenberg, I had the pleasure of meeting you recently.” Rudolf Steiner Archiv. RSA 088.

- Harden writes about him that he read to the Prince from books “he did not know,” and that he “had followed in the footsteps of Mrs. Blavatsky quite far into the nebulous realm of esoteric Buddhism. A magus from Romania or Bukovina.” Die Zukunft (May 16, 1908): 236. Jaroljmek had been a member of the Theosophical Society since Oct. 1906, for a short time, at least.

- Rudolf Steiner Archiv. RSA 086.

- Letter of December 28, 1906. Philipp von Eulenburg wrote to Rudolf Steiner about the meeting on December 21, 1906: “Sigwart [the Prince’s son] had the feeling that you had been too considerate. I would believe the same with L.[ycki]’s stubborn character.—In any case, I would be grateful if you would stay in close contact with her; for example, write to her quite soon. I leave it to you to decide whether you should reinforce your communications. . . . How can I ever thank you for all your kindness!?—I think of you with great emotion!” RSA 086.

- The situation with the family was exacerbated by the fact that Karl von Eulenburg [Prince’s youngest son] apparently also sided closely with Jaroljmek. At least, this is suggested by the words in the letter from Philipp von Eulenburg dated December 30, 1906: “My son has broken his word of honor and has now informed me that he has decided—whether the sister marries or not—to stay with J[aroljmek].” See footnote 24.

- Rudolf Steiner and Marie Steiner-von Sivers, Letters and Documents, 1901–1925, CW 262, (Forest Row, East Sussex: Rudolf Steiner Press, 2019, repr.), 102. Shortly before, Rudolf Steiner had answered the question of whether the press could be used for “agitation” after a members’ lecture: “In general, this should be rejected because the press is corrupt. Example: In connection with the Harden trial, there is a case where a newspaper reported objectively falsely about a person; when it then had to run a correction, it added the words: This settles the case for us.” Rudolf Steiner, Fragenbeantwortungen und Interviews [Answers to Questions and Interviews], GA 244 (Basel: Rudolf Steiner Verlag, 2022), 188.

- Parts of the notes about this were first published in the 1950s under the title Brücke über den Strom [Bridge over the Stream]; there have been numerous and expanded editions since then. Anonymous, Bridge over the River: After Death Communications of a Young Artist Who Died in World War I (USA: Anthroposophic Press, 1974).

- Copy of the letter in the RSA 086.