In June 2024, there was a staged reading of Jacques Lusseyran’s Das wiedergefundene Licht [And There Was Light]1 with Richard Schnell, Fritz Nagel, and a sculpture by Barbara Schnetzler. One member of the audience, Aina Bergsma, left the six-hour program feeling “ge-ich-tet” [‘I’-ed] and offers her reflection.

In a time where complexity constantly threatens to overwhelm our comprehension and repeatedly disorientates us, I long for light. Light, not as enlightenment from above, as divine input, nor light as illumination of an “objective reality” through facts and figures. I long for light as it appears in an ‘I.’

There are people who are so strongly ‘I’-ed that their ‘I’ shines beyond the borders of themselves. Sometimes you meet such a person physically, but most of the time, the encounter is indirect, through their works. Their music, their dance, their poetry—their expression—leaves an imprint of their ‘I’, communicates it to the general public, so to speak. And we who are privileged to receive this imprint are touched by the light of this self.

This encounter, this contact, is like a person who is alone in the dark sea, perhaps shipwrecked, and suddenly sees the glow of a lighthouse. The lighthouse itself is not salvation, but the mere presence of this beacon of light provides orientation and hope in a powerless situation. Contact with a human lighthouse tells me that there are still human forces that can spread light in the darkness and that are not swallowed up by it.

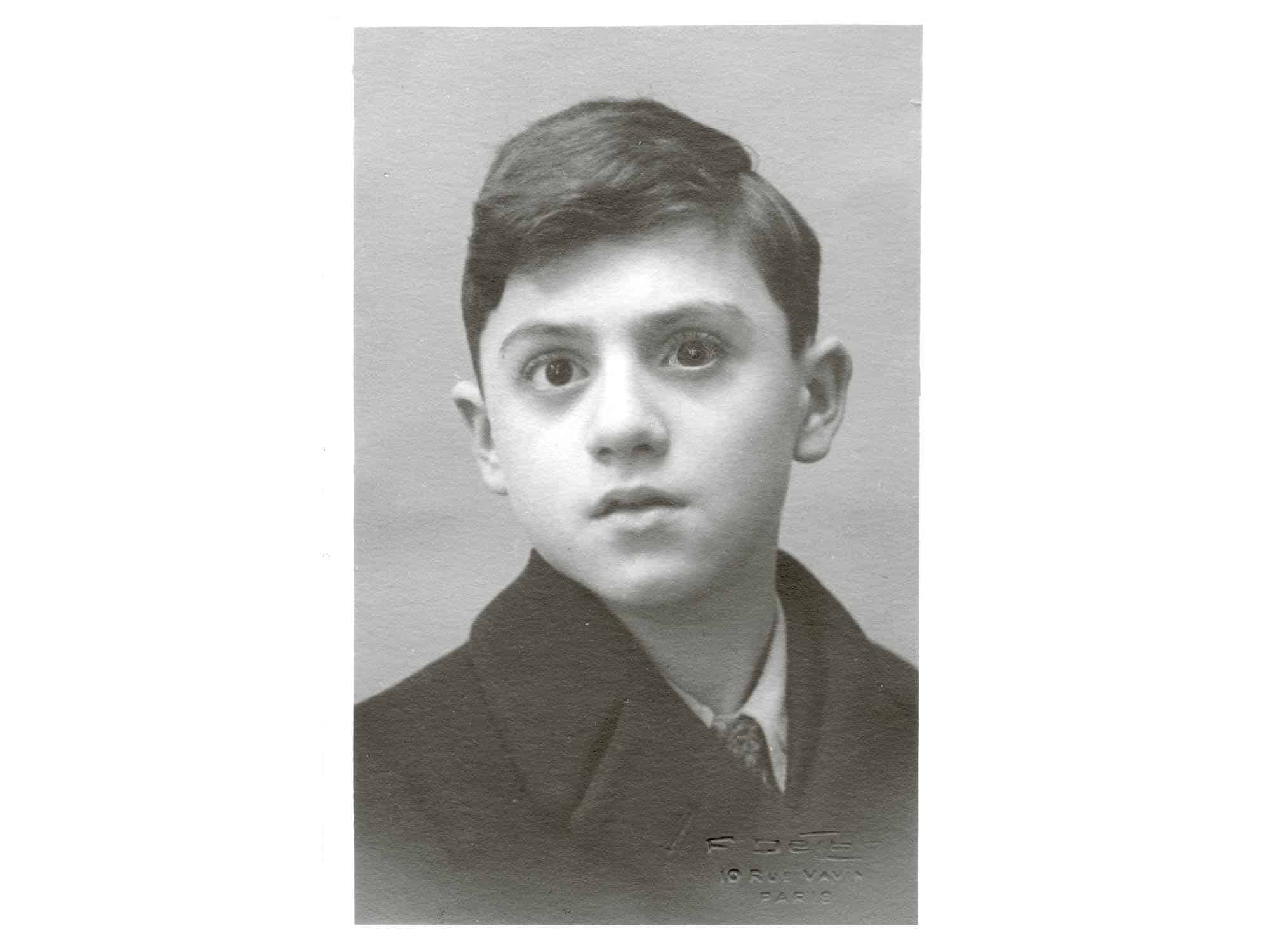

Jacques Lusseyran (1924–1971) lost his sight when he was just eight years old and found it again not long after, within himself. The world spoke to him in a miraculous way through sounds and pressure sensations, but also through light. When something good and loving was present, the inner light appeared strong and clear to him. When he encountered something deceitful and evil—in others or in himself—the light dimmed and disappeared, leaving him disorientated and truly blind.

Lusseyran’s biography, which he depicts in his book And There Was Light, is a journey through inner and outer realms, described by a man whose “blindness” became a gift for perceiving the world and human beings. He tells us what his world looked like, a world that, during his youth, was shrouded in the darkness of the Second World War. By following his inner light, he took a path that led him into political resistance, prison, a concentration camp and from there out again.

The biography of this ‘I’ is a beacon in book form. I was able to experience it as a reading this summer, in 2024, the year in which Jacques Lusseyran would have celebrated his 100th birthday. At St. John’s Day, the actor Richard Schnell and the musician Fritz Nagel, re-presented the written expression in words and sound. They took us listeners on a journey through Lusseyran’s childhood in three parts—through his work as a young resistance fighter and finally through his time in the Buchenwald concentration camp.

We spent over six hours (including breaks) traveling together with the light of Jacques Lusseyran. Yes, with the light, because the light flowed from the words and from the sounds that were spoken and played. The story of Lusseyran gained materiality through its connection to the human voice, through its embodiment in a human form. Richard Schnell’s reading was subtle and powerful, and it was more than just a reading: he shaped Lusseyran’s words linguistically in such a way that the colorful, multi-layered world of a blind man began to shine.

A luminous figure stood next to him the whole time, created by the sculptor Barbara Schnetzler. It was a disc made of Carrara marble in which horizontal and vertical cracks formed the shape of a cross. A light source behind the disc, which was made stronger and weaker during the performance, changed the glow of the stone cross figure. The darkening and brightening of a cross in the room intensified the experience of being close to the light and the self.

Neben ihm stand die ganze Zeit hindurch eine Leuchtfigur. Das war eine Skulptur der Bildhauerin Barbara Schnetzler, eine Scheibe aus Carrara-Marmor, in der horizontale und vertikale Risse eine Kreuzform bildeten. Durch eine Leuchtquelle hinter der Scheibe, die während der Aufführung stärker und schwächer eingestellt wurde, veränderte sich das Leuchten der Kreuzgestalt aus Stein. Dieses Eindunkeln und Aufhellen eines Kreuzes im Raum verstärkte das Erlebnis, dem Licht und dem Ich nahe zu sein.

For me—not really shipwrecked yet a traveller on an open and sometimes dark sea—this experience on St. John’s was a lighthouse. My doubts and fears, my shadows, encountered something powerfully luminous. Weren’t there four ‘I’s working together artistically here? Did this performance shine so brightly because it combined several ‘I’ forces?

Now, in winter, I look back on this performance with gratitude and feel the light imprint it left on me. It didn’t necessarily enlighten me: my fears and worries didn’t dissipate afterward, and the redemption wasn’t permanent. And, looking back, my mind probably gained little: theories and facts were only sparsely available in the performance, so I have nothing I can hold onto with which I can argue and persuade. What I have is hope. Hope that the light can withstand the darkness—in a person, in a world.

Translation Laura Liska

Image Jacques Lusseyran, 1933