Kafka and the Anti-Semitism of 2024. On the 100th Anniversary of the Writer’s Death.

I have no mandate and am not a moral authority. I am just a citizen who is amazed at how we have left Jews, our fellow human beings, alone since October 7, because that is how many people are experiencing this moment. I don’t understand the priorities we set. I don’t know what it feels like to live with the knowledge that you are to be exterminated. Even as a student, I didn’t understand why Jews were considered an enemy. Am I playing dumb? Is one allowed to say: “I don’t understand”?

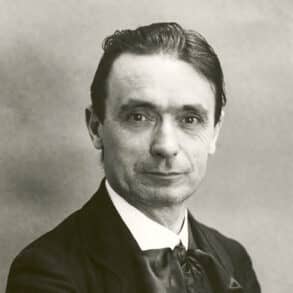

This one sentence: “I don’t understand,” is perpetually stated throughout the work of Franz Kafka, whose death we commemorate in 2024 for the hundredth year. “I don’t understand myself; I don’t understand the world.” Without even saying, I understand “no more.” “I’ve never understood them. What do I have in common with Jews?” he asked himself. And added: “I don’t even have anything in common with myself.”1

We are moved when Holocaust survivor Margot Friedländer reminds us that we are all just human beings. What does that mean? We are, indeed, not yet fully human. We don’t even understand what it means to be human. We do not yet have a full consciousness of our humanness. We only know how it operates: our brain, our body, our intelligence, and we even use them outside of ourselves. But, we have not yet descended into our powerlessness. We are afraid of the abyss of not understanding. We would have to sink ourselves into the consternation of the Jews, our fellow citizens, and why they are so hated—slowly, carefully, fearing that it would tear our soul apart, as if into a tomb made for the light; we would have to let ourselves go into the soul of the other. Kafka could teach us that this hesitation before judgment is the only possible moral stance for human beings today. All around us howl the sirens of snap judgments, crafty assessments, and hysterical commentaries. For Kafka, even going to the post office was a mystery. Before she was murdered in the Ravensbrück concentration camp, Milena Jesenská2 was one of the few who understood why business-minded people were a mystery to him. When one distances themselves from human beings—like Kafka’s father from his son’s Eastern Jewish3 friend— because they remind them of their own weakness, the ranks must be closed off, otherwise the store wouldn’t run.

At the Entrance to Hell

I don’t comprehend any of the clichés. Perhaps Judaism, historically speaking, is the threshold of a profoundly human incomprehension that we all share. Kafka said he was the end or the beginning. He saw himself as an individual. He had not caught the last corner of the Jewish prayer shawl, nor did he believe in any other external god. The student Kafka wrote that we had to stand before each other as before the entrance to hell: lovingly, reverently. Because the other would never be able to express what it looks like inside him. A Muslim also cannot fully express his experience when he goes along, almost in reflex, with the Jewish hatred arising in his fellow Muslims because otherwise, they would mistrust his standing as a Muslim. We multiply hell. We do not stop thinking in terms of collectives. We are not interested in the individual, only in our own interests. This applies to trade associations as well as to Berlinale [film festival] communities, to political parties as well as to activists. Everyone is only looking out for themselves. Thinking in terms of face-saving strategies is our silent consensus. Kafka couldn’t think strategically. He didn’t want to. Or wanted to no more. When he did, it went awry. Then, it all became artificial. Then, he artificially sought advice from Rudolf Steiner; then, he artificially looked for a fiancée.

The conclusion of a grief that, after a long journey through life, has arrived at an attempt at forgiveness is that statement, “We are all human beings.” We feel shame when facing this. But, our own morality is becoming senile. It is stirring itself. I don’t want to “speak out against anti-Semitism,” not even “against hatred and agitation.” Isn’t everything nowadays just some form of incitement? Sometimes direct, sometimes subtle. I shy away from these phrases that only glaringly emphasize what they want to overcome. How can we morally rejuvenate ourselves? Not by occupying concepts, like occupying neighboring countries. Not by agreeing on language rules, wordings, and framings and fighting for interpretative sovereignty. Regulated speech is dead speech, and just because everyone is doing it, it seems justified and part of business acumen. But it’s just a play with lies.

Naked and Needy

We have to become as children who don’t understand, who, as in Andersen’s fairy tale, name what is clearly visible: the emperor is indeed naked. There is nothing that could seriously establish that a certain blood, the outward physicality of a people, must endure centuries of stigmatization. Children are astounded. What’s the point? They laugh, because it’s ridiculous. The child sees through our prejudices, the ascribed shells, the foolish automatism of authority. (Kafka had a laughing fit when he was promoted.) The child sees the naked, needy human being. Understanding lies in not understanding. This is where a path begins—in pausing. For Milena, Kafka was a “naked man among the clothed,” one “without refuge.”4 He himself called his life the hesitation before birth. And if there was transmigration of souls, he was not yet at the lowest level. The inexhaustible number of interpretations of his body of work is not an academical statement but a moral one.

We must surrender to this openness when we lie naked before each other as bodies and try to read the will of the other and trust each other. But how? When does misinterpretation begin? When does abuse begin? Here, we could start with the mutual recognition of “I didn’t understand you,” with “I had nothing in common with myself,” and “I am the end or the beginning,” just like you. I want to turn the times around with you! I want to return to the threshold. To meet not “before” and not “after” Christ, but in him, in such humanness, in powerlessness, in death. In Kafka’s aphorisms, the Messiah only comes “when he will no longer be necessary.”5

We would have to manage to no longer be identifiable but to identify with the other again and again, actively instead of passively, and under all circumstances. The decisive moment of development is everlasting, wrote Kafka, which is why all revolutionary movements are right, “because nothing has yet happened.”6 I wish that nothing will happen to the Jews, my fellow humans. I wish that no one says that this or that has rightly happened to anyone. It rightly happens for no one, even for the others. How could one of the many different human-social aspects of conflicts be valued more highly than another? From what perspective? How could one biography ever be more relevant than another, or how can lives be ranked differently? Or do I just want, like Kafka, to please all the people all the time? I want to think that we are all connected. Like a shared wound.

Translation Joshua Kelberman

Footnotes

- Franz Kafka, Tagebücher. Kritische Ausgabe [Diary. Critical Edition], edited by Hans-Gerd Koch, Michael Müller, and Malcolm Pasley (Frankfurt, Germany: Fischer, 1990).

- Milena Jesenská [1896–1944], Czech journalist, writer, translator, and romantic friend of Kafka. See Franz Kafka, Letters to Milena (New York City: Schocken Books), 1990—Trans. note.

- “Since the Enlightenment, the image of the ‘Ostjuden,’ ‘Eastern Jews,’ has played a crucial role in German Jews’ self-definition. Jews from Eastern Europe were considered backward. This backwardness seemed to endanger the German Jews’ integration into modern society. Therefore, they repudiated the ‘Ostjuden.’ At the same time, there emerged a sense of collective responsibility for their ‘weaker brothers.’ At the start of the 20th century, a positive countermyth was established. The unspoiled nature of the ‘Ostjuden’ was turned into a cult” [celebrated by the Zionists]. Steven E. Aschheim, “Reflection, Projection, Distortion: The ‘Eastern Jew’ in German-Jewish Culture,” in Osteuropa [Eastern Europe] 8–10 (2008): 61–74—Trans. note.

- See footnote 2: Letter to Max Brod, beginning of Aug. 1920.

- Franz Kafka, “The Coming of the Messiah,” in Parables and Paradoxes (New York City: Schocken Books), 1969.

- Franz Kafka, The Zürau Aphorisms (London: Harvill Secker, 2006), aphorism 6.