Ecstasy and asceticism are states of the human soul in which nearness to God plays out. They are extremes that make it possible to swing from the divine to the human and back again. A free liminal interplay is created between the concealed and the revealed.

One of the oldest and most popular games in some, if not all, cultures is when a child hides and then suddenly, with a loud shout, bursts out to reveal themselves. Although the parents know well ahead what is coming, it never fails: great excitement, squeals of laughter, falling on each other with shrieks of terror, until the inevitable “Do it again, do it again!”

It is a game that can be played anywhere and in any situation. All you need are players and a desire to play. A scarf or an oversized hat is enough. Or just two hands held in front of the face: “Look, look, where am I?” Until someone can’t bear it any longer and peeks through their fingers.

What is at play here? Two opposing inner emotions collide. One is where we pause motionless and under control. We contract completely. The other is where we let ourselves go without inhibition. Being able to control ourselves, however briefly, requires practise. The tension that arises in this dissolves in the counter-movement: asceticism and ecstasy. The more concentrated the contraction, the more exuberant the release. Laughing and crying, crying and laughing—the archetypal gestures of the soul! However, play only reaches its true reality in the space in between—between asceticism and ecstasy. (For, according to Friedrich Schiller, it is only between the urge for form and the urge for substance that we become free!) If we were to reveal ourselves immediately in this game of hide-and-seek, if we were to immediately rip off the covering—which some children indeed do because the tension is unbearable—then the game would implode. The moment of freedom has been preempted by the all-too-rapid transition. The game collapses. The pleasure and joy of the game become boring and tedious.

The archetypal experience of play arises between asceticism and ecstasy. The mask can make its appearance in this in-between space because concealment makes the unveiling possible. A mask is both a guardian and a threshold at the same time. It causes us to stay in the in-between. Between concealment and unveiling, I am, for a moment, lifted out of linear time. I am touched by a breath of Aion, of eternity.

Not so long ago, the word “mask” was the cause of heated discussions in which for and against attacked each other, and many people stayed in their trenches. The point was not so much the mask but rather the command by a higher authority, a state institution, to wear it. A free decision was preempted; play no longer stood a chance.

The Human Condition

The mask is part of the reality of human life, of our “condition humaine“. Masks from the remote past still bear witness to this. Most were ritual masks that played a performative role in initiation rites or magical practices. In the early development of humanity, the mask pointed to an immanent boundary between the divine and the human, or it referred to a taboo.

On the one hand, the mask protected people from the immediate sight of God, whose overwhelming epiphany in every respect could lead to confusion and even destruction. The sacred was to be protected in its power of revelation. This is why the deity appears concealed by a mask. At the same time, the human being is also protected.

Conversely, it is the human being who ritually conceals themselves and withdraws from the view of others—they mask themselves. The shaman, when performing a ritual act, wants to protect the uninitiated from possible destruction during this act. On the other hand, he himself comes into risky proximity with the numinous. He walks on the border between life and death. He may even cross it for a moment. The mask anticipates his vulnerability and transforms him into a shaman who is equal to the risk.

It still took some time before it became possible for a deity to reveal themselves on earth without a mask, which became the reason for the composition of icons.

Classical Catharsis

The theatre masks that every theatre had in the Greek classical period are probably the most well-known. Often made of clay, more rarely of canvas or wood, they depicted the two varieties of classical Greek drama, the tragic and the comic, using prescribed features and facial expressions. In the tragedy, the masks expressed deep suffering through strongly accentuated frowns, furrowed brows, and lamenting, painful facial features. In the comedy, the masks represented laughter using wide open mouths and mischievous or even satyr-like features. Weeping and laughter were the outermost boundaries within which gods and humans, and between, them the choir depicted their interlinked destiny.

As the theatre had grown out of the Mysteries, where covering the head and face of the mystic was a strict requirement, this also applied to a theatrical performance. Theatre, similar to the mystery dramas in the initiation process, definitively had the purification of the soul as its goal. In his Poetics, Aristotle described the two poles of catharsis: éleos and phóbos—pity and fear (Aristotle, Poetics, 1449b, 6, 25, LCL 199).

In fear, the soul is completely contracted; in pity, it expands again, as when taking a breath. Purification takes place in the movement between these two extremes. This brings the soul into a momentary state of equilibrium and makes it receptive to the deeper meaning of the theatre play. The happening is intended to evoke trembling and lamentation.

“Tragedy is the imitation of an action of a certain magnitude that is good and complete, in attractively crafted language (…)—imitation by actors and not through narration that provokes wailing and trembling and thereby effects cleansing of such states of emotion” (Aristotle, Poetica 6, 1450a, 6, 30 ff., LCL, 199).

Prosopon and Persona

Unlike in the rituals of early times, where the person wearing the mask and the divinity revealing itself merged into one another, in the theatre, the mask was differentiated from its wearer. The person was expected to put themselves completely at the service of the role. They “carried” their role; it weighed on them, which, given the material weight of masks at the time, must often have been the case.

The Greek word for mask, “prosopon”, when translated into Latin, became the word “persona“. From the twentieth century onwards, the term person or personality developed from this in psychology and related sciences. It was suggested that “persona” meant that which sounds through the mouth opening of the mask—sonare means “to sound”. This is not correct in several respects. For this meant, for example, that it was possible for the person wearing the mask to make themselves audible as a “person”, something which, according to the rules, was not permitted in classical theatre.

Nevertheless, when someone comes out wearing a mask, I become curious as to who is behind it. There is no mask without a person behind it. But who is wearing the mask? Who is wearing the mask in me?

The masks worn during ritual ceremonies did not permit this question. The mask and who it represented were so fused together that the question of who was behind it would have been completely meaningless. No one is behind it! It was the deity itself that revealed itself with tremendous might, and no one would dare question this concealment. And although the theatre has never denied its ritual origins, an awareness gradually arose that there was someone behind the mask. But this person was in the service of the god of the theatre, Dionysus, and as an actor, they were supposed to give up their own identity. Only the deity was entitled to reveal their countenance because the human being would not survive such revelation!

How, then, can “prosopon“, πρόσωπον, be interpreted? There is no unequivocal translation. In the Christian orthodox view, “countenance” means that which can reveal what has only become reality since the incarnation of Christ and, therefore, takes place in the icon. The icon shows how the mask can become a countenance, in that a God has revealed himself, unveiled, in a human face.

When the Countenance Becomes a Mask

Nowadays, the mask has given rise to a wide range of possibilities to conceal oneself or reveal oneself. Both paths are open, whereby each mask is either restricted to that which conceals my individuality and even allows me to hide behind a borrowed cover, or that which imposes a role on me that burdens me or, on the contrary, delights me. I can conjure up any kind and shape of mask in my imagination and transform myself from mask to mask, without a caesura between one and the next. But is there still someone else behind it?

In social media, self-presentation often becomes a mask, even if it involves a barely filtered or unfiltered photo of a face. Basically, it can no longer become “prosopon“—countenance—bound as it is by the effect of the medium. Because nothing can stand behind it any longer, it lacks any transparency. Facebook—literally a “book of faces”—from which the aura, the spark of what is individually human, has been filtered out, is a book from which the history of becoming human has been wiped.

We could imagine humanity as a single image, as an all-encompassing “human countenance”. A countenance into which has flowed the past, present, and future of humanity. This human countenance is shattered when it can be copied infinitely. Then, behind each mask, there is another one. Self-presentation serves the illusion that this is a true countenance, while technology deludes us into believing that there are always “new” possibilities.

Left: Hand puppet by Paul Klee, Untitled (Crowned Poet), from 1919, height 35 cm; Right: Hand puppet by Paul Klee. Untitled (socket ghost), from 1925, height 35 cm; All hand puppets: Zentrum Paul Klee, Bern, donated by Livia Klee.. CC BY-SA 4.0 DEED

Fasting

Consider the Christian season of Lent. Every year, like a self-contained temporal shape, it marks a caesura—an open space between an everyday life woven from familiar habits and a high level of celebration that we are not equal to.

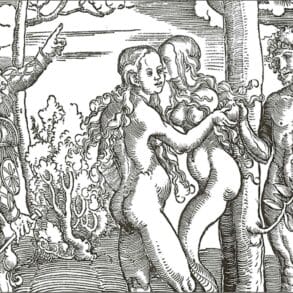

Fasting during Lent can be alienating and unsettling, as if we have shed our skin too early and do not yet know how to protect ourselves from the cold and heat. We are like the first human couple on their first steps out of the paradisiacal cocoon, not knowing whether they should also plant their other foot on the ground.

Lent can also pass us by completely. We have largely lost an understanding of what fasting represents as an action and how to do it. When someone avoids certain foods for a period of time for self-imposed reasons, we often hear: “I’m fasting a little for these weeks.” Even if it is not easy, such fasting gradually integrates itself into everyday life. We grow accustomed to it and forget it without realising that we have forgotten it. From then on, it becomes part of our routine; it is no longer an interruption to this routine.

Fasting means practising—practise as self-discipline based on religious or philosophical motives. In Hellenistic times, it was a widespread form of self-training, the main aim of which was to master one’s affects and instincts and to learn to bear emotional pain with sovereign composure. Voluntary renunciation of comforts and luxury foods was part of this, but so was maintaining oneself with dignity in difficult life circumstances. This can be seen in the example of Seneca, who was able to transform his imposed death into a voluntary death.

The “ascetics”, ἀσκητής—”those who practised”—traveled throughout the Mediterranean region around the turning point of time (in the post-Christian centuries, for example, in the deserts of Palestine, Syria and Egypt) and tormented themselves in every conceivable way in addition to their practise. Their everyday life was an uninterrupted fast, during which they were tormented mentally by the demons exorcised from their bodies. Here, fasting is not a caesura either.

If fasting nowadays has become part of everyday life worldwide, the only thing that remains as an original caesura, a turning point between asceticism and ecstasy, is Shrove Tuesday. It is the moment when we can abandon ourselves without restraint. In many cultures, masking and masks are part of it. The ecstasy is there for all to see. But where is the contraction of the self in asceticism? Where does the space in between open up again? Because only in the space in between can the living be celebrated in its true form of the dual dynamic—when the child plays and time holds its breath for a moment.

Translation Christian von Arnim