Autobiographical notes by Bruno Walter (1876–1962) on the life crisis in his youth show the two activities of the I, which Viktor Frankl later described as primordial human abilities.

Not far from my apartment, on a street corner, there is a discarded telephone booth converted into a bookshelf. There I was recently able to borrow an old copy of Bruno Walter’s work, ‹Thema und Variationen› [Theme and Variations].1 Bruno Walter was a conductor as well as a student and friend of Gustav Mahler and, in his later years, an anthroposophist.2 In this book, I unexpectedly found a beautiful illustration of the topic that has kept me particularly busy in recent years: self-distancing and self-transcendence, as Viktor Frankl describes the «primordial human abilities» that he «verified and validated» in the Auschwitz concentration camp.3

It is about a crisis that Bruno Walter experienced around the age of 21 when, after unsatisfactory experiences in Wrocław, he received the offer to take over «the position of first conductor for the 1897–1898 season» at the Municipal Theatre of Pressburg (later Bratislava). There, he was able to test his strength in preparation for a larger task that awaited him in Riga the following year. He writes:

Well, I decided I wanted to start becoming myself. […] I realized that the prerequisite for an activity such as the one I had planned for Bratislava was self-purification. I decided to keep a diary that would illuminate, direct, and admonish my behavior in daily records. […] In regular sharp observation, I wanted to recognize who I actually was, wanted to hold myself to the highest standard, examine myself, criticize, and even dissect myself. No critic in my long career has dealt with me as ruthlessly harshly as I did in my self-criticism; it brought me to despair […]. My criticism was not only directed against my music-making but against the totality of my nature and behavior. Even though it wasn’t supposed to be criticism, it was hostile from the outset.»

There is still talk of «self-destructive brooding.» Is that me-like? Walter speaks of «despair» and «gloom» that spread within him, finally of «a crisis that seriously threatened my mental health.» A deep resentment against himself grew within him. «But my self-vivisection helped me neither to achieve improvement nor inner peace.» The young I, which distanced itself from its own spiritual organization, gave birth to itself from the soul, so to speak, had not yet fully come to itself. It was not immediately capable of harmonizing the powers of the soul, of positivity and impartiality.4 It couldn’t even get the thoughts under control: «The tormenting thoughts […] soon left me no rest day and night, and I felt powerless and almost without will drifting towards a catastrophe, like a swimmer who succumbs to the violence of treacherous water vortices.»

What to Hold on to?

The I is able to observe the emotional events without judgment and place them in a larger context, from which it can decide how to deal with them. Bruno Walter’s crisis clearly points to an identification with an over-critical, negatively minded part of his mental organization. It can be understood as being carried away with the self-distancing dynamic. A conscious identification with the newborn, i.e., an identification of the I, should have been preceded by an equally active disidentification of this self-destructive force. This was further complicated by I-denying philosophical theories, which Walter dealt with. How could he free himself from this «fruitless introspection» and arrive at effective self-purification? How did his I powers work in this crisis? They aroused a question that pointed beyond himself: «Had everything really disappeared from me? Couldn’t I stick to anything anymore?» It distracted him from himself, to where his sentient life found what could sustain him, like nothing else external or internal, nothing material or merely spiritual that could: «One day – perhaps I had just had a musical experience – my diary answered with the counter-question: Why don’t I recognize music as my reality? […] Everything material might be unreal: its immaterial nature was certainly no sensory deception. So I had an undoubted reality to which I could hold on deeply.»

Music led him to experience creativity in human beings. «And wasn’t there the inspired, creative human being, a mediator between me and the divine, and didn’t each of his works have a reality beyond all problematic reality? Could anything be more real than Goethe’s ‹Faust›? The reality of the spiritual comfortingly made sense to me to the extent that the world shadowed itself to me.»

Self-Transcendence

In the I activity, one can always distinguish between negative and positive sides.5 The negative creates distance and thus space for a positive that can fill the space that becomes free and thus only helps the repressive negation gesture to its actual meaning. The intentionality of the I holds the two sides together in a bridging way. Self-distancing is followed by the second step of the I: self-transcendence, the transcendence of bodily and spiritual existence towards an individual, which is at the same time universally human and worldly. In this case, it was music to which Bruno Walter obviously had an extraordinary individual affinity and talent. His devotion to reading was not purely inward. In addition to his reading, it also pushed into his external work: «The fact that I was able to concentrate and work fiery and optimistic under such mental pressure is one of the strangeness of my nature that I cannot comprehend.» Also his I-nature? He wrote even before Riga: «I began […] to look outwards again, to be interested in foreign surroundings, ‹to live resolutely›, as Goethe recommends.» This may finally be the keyword for the second I activity. ‹To live resolutely› – combined with an active interest in the outside world, even in the other in it, the foreign.

The Breathing I

This description by Bruno Walter shows us what Frankl calls the primordial human abilities – self-distancing and self-transcendence – as related aspects of the I activity. This can also weaken or requires conscious practice. In their respective one-sidedness – losing oneself to the world or wearing oneself down in an infertile self-analysis – the partial steps endanger the mental and spiritual health of the human being. In their combination, however, they establish healthy individual development. The world is then actively involved in the self-distancing retrospective. The fruits of this kind of self-reflection flow into the power of the decisions with which I turn to the outside world. Not in the form of specific goals and predetermined criteria, but as a willful life effect, as a force in alignment. Once I understand this, I will probably not try to live with the handbrake on, nor will I run after everything that imposes itself on me without judgment. But I will want to breathe in and out as deeply as possible. That is, to give me to my life in the world, as it comes to me from the outside – and from the inside. And I consciously create moments of escaping the flow during the day, during which I visualize myself uninhibitedly. The more I can rely on these moments to come, the more trusting and devotional I can confide in my destiny. I notice that I become more awake. And the deeper I get involved in my life, the more fruitful my review will be. All in all, my life becomes richer and more lively, more livable – in a way that also benefits the greater whole, as the biography of Bruno Walter can testify to exemplary. Thanks to the book booth.

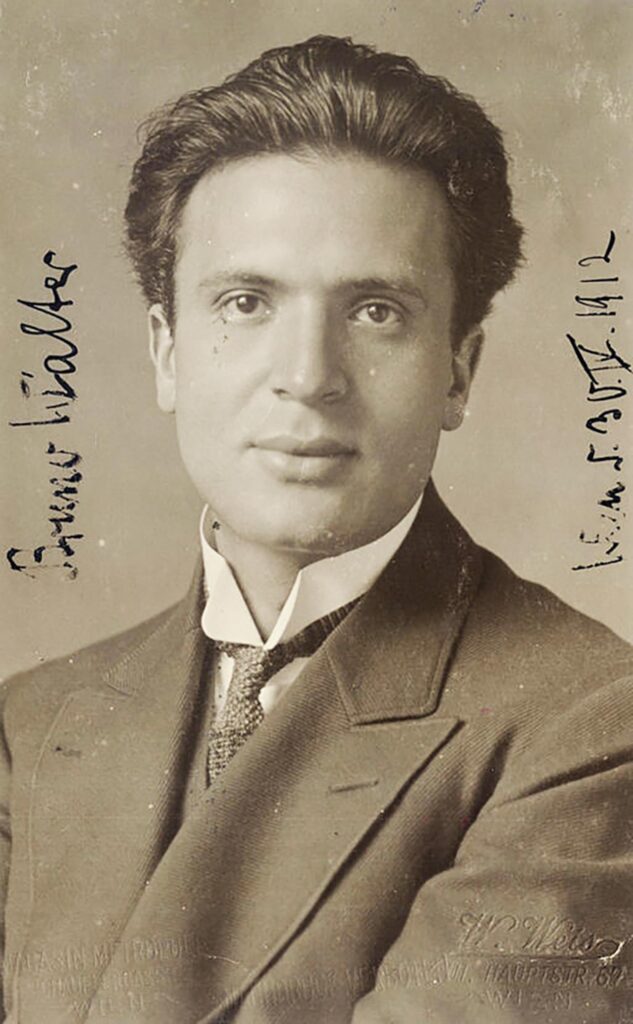

Title image Bruno Walter, 1900. Source: Library of Congress/USA

Footnotes

- Bruno Walter, Thema und Variationen. Erinnerungen und Gedanken. [Theme and Variations. Memories and Thoughts.] Frankfurt/M. 1950. All quotes from Walter are from the book.

- Bruno Walter, Mein Weg zur Anthroposophie [My Path to Anthroposophy]. In: Das Goetheanum 52 (1961), p. 418–421.

- Viktor E. Frankl, Dem Leben Antwort geben. Autobiographie [Answering Life. Autobiography]. Weinheim 2017, p. 120. See also: Rudy Vandercruysse, Wo bist du? Der Weg des Menschen und die innere Praxis der Selbstführung. [Where Are You? The Path of Human Beings and the Inner Practice of Self-Management.], Stuttgart 2021.

- A more differentiated view of human knowledge could point here to the sequence of stages of the sentient, intellectual, and consciousness soul initiated by the I activity. As a result, Walter was at the beginning of the development of his sentient soul, which wakes up from self-experience. An unbiased, disidentified introspection is only possible for the consciousness soul. See e. g., Rudolf Treichler, Die Entwicklung der Seele im Lebenslauf [The development of the soul in the course of life]. Stuttgart 2012 (7. Ed.).

- See Rudy Vandercruysse, Herzwege. Von der emotionalen Selbstführung zum meditativen Leben [From Emotional Self-Management to Meditative Life]. Stuttgart 2022 (New Edition), p. 82–84 und p. 115–117.