A conversation about the completion of the Collected Works (CW) [Gesamtausgabe (GA)] and the handover of the archive’s leadership was held with those currently in charge of the Rudolf Steiner Archive and those who will soon be.

Wolfgang Held: These are special times for the Rudolf Steiner Archive. The project of producing a complete edition of Rudolf Steiner’s works is in its final phase, and at the same time, Angelika Schmitt and Philip Kovce have begun their induction period. In the coming Easter, they will take over from David Marc Hoffmann as directors of the Archive of the Rudolf Steiner Estate Administration [Archivs der Rudolf Steiner Nachlassverwaltung] under Board President Cornelius Bohlen. How are things progressing?

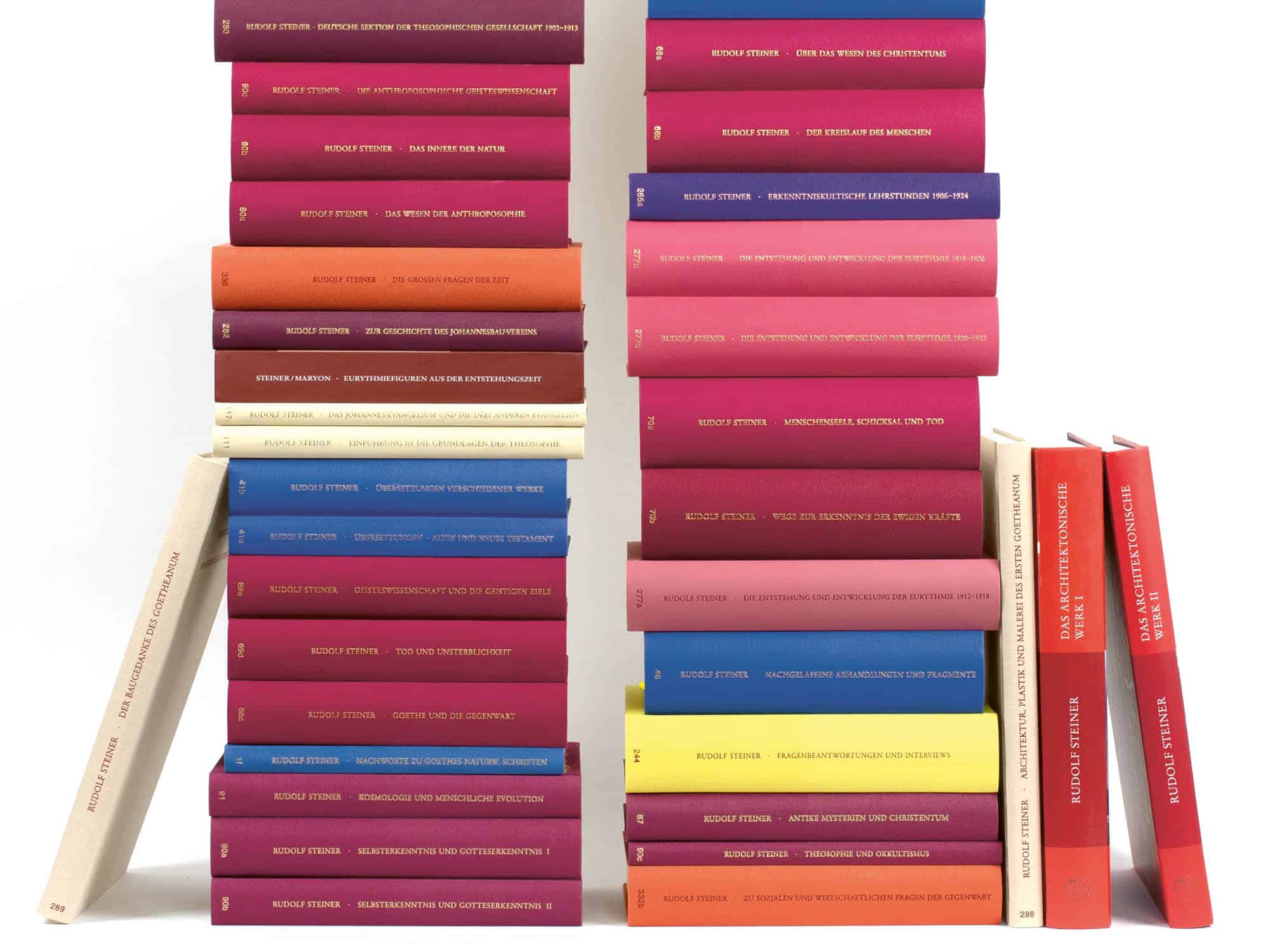

David Marc Hoffmann: We defined the “GA 2025” project in 2016, almost ten years ago. It seemed obvious to us that the Complete Works, which began in 1961 for the hundredth anniversary of Rudolf Steiner’s birth, should be completed for the hundredth anniversary of his death. In 2016, we started with a publication plan of around 60 outstanding volumes. And it looks like we will finish almost right on time.

At the time, there was skepticism about whether it would succeed, wasn’t there?

Hoffmann: We invested a lot of time in resource planning. We determined the workload required for each individual volume: one volume could take half a year, another a whole year, and a third a year and a half. Then, we listed the necessary finances and the time required and distributed the volumes across the ten-year period from 2016 to 2025 and amongst the individual employees. In our calculations, we did not include the new editions of the GA that were out-of-print or new editions of the written works of the GA that are based on the last authorized edition, that is, the last edition approved by Rudolf Steiner himself. During the project, we realized that a reliable, consistent basis for the written works would also be needed. In earlier years, such a basis was not developed in the way we would wish it to be today. This led to the decision to work through all the texts based on their last authorized editions. There were, and are, older editions in which different manuscripts are mixed together, and it is not all presented as it should be today, according to good contemporary editorial practice. Moreover, we had not considered the actual fabrication of the books. Our calculations only went as far as the print-ready manuscript. Typesetting the text, proofreading, printing, and bookbinding—we hadn’t factored in any of that. But now, we are in the gratifying and also daunting position of not only seeing the home stretch but even the finish line. That means a lot is still to be decided in these last few miles, and so we still have a lot to do in the remaining year and a half.

How did you manage to overcome the financial shortage of three or four years ago?

Cornelius Bohlen: Yes, in 2016, we weren’t sure how our plan to complete the Collected Works would be received. We were really pleased that there was a positive response from the anthroposophical movement, the Anthroposophical Society, friends, and supporters. The first few years were able to be financed by donations. We also received small bequests. Then came the fifth or sixth year when we weren’t sure whether the project would actually be financially viable for the whole ten years. Some foundations stopped their support because they changed their funding priorities or had exhausted their funds. Nobody opposed the project, but suddenly it was questionable whether we would get the approximately 1.7 million francs we needed each year. Only at the end of the year did it become clear whether we would be able to continue based on the summation of all our support, not least thanks to the many small individual donations. Even today, we still don’t know whether we will be able to finance the coming year. We still need around 1.4 million francs. But, the experiences of our years of crisis have given us confidence that we will actually be able to complete the Collected Works in 2025.

Hoffmann: At the beginning of this journey, there were also doubts: the Collected Works had already been completed, so it was thought. But, we showed that essential volumes were missing. Now, a volume has been published that documents Rudolf Steiner’s lectures in the Masonic context (GA 265a). This was entirely unknown. We are also working on a complete edition of letters in six volumes (GA 38/1–6), the first three of which have already been published. Previously, we only had a two-volume selection of letters. In addition, we have edited four volumes of public lectures from the time of the First World War, which were also unknown (GA 70a/b, GA 71a/b), as well as a volume of Steiner’s translations of the Bible (GA 41a), which was so successful that it had to be reprinted within a few months.

Bohlen: David Marc Hoffmann refers to the difficulty that arose in the course of the project: new material was repeatedly found that needed to be published. The project did not get smaller. For example, there will also be a new edition of the supplementary volume to Steiner’s verses, which contains around 400 verses or variants of verses that have not yet been published (GA 40a).

Hoffmann: It has become apparent in the process of completing the Collected Works that not only Steiner’s lectures but also his written works contain unknown elements. These are, of course, the welcome surprises that repeatedly thwart our planning.

Is the completion of the Collected Works a gift to Rudolf Steiner and/or to the public?

Bohlen: Doesn’t the public deserve to have access to all the phases of his work in a transparent and accessible way? I think that Steiner is best understood by surveying his whole work—from his early philosophical writings to his last fragments. This makes it easier to comprehend him and his work, indeed his entire life, as a life’s work. That is the purpose of the Collected Works: to make Rudolf Steiner, in all his facets, perceivable and researchable.

“We started 2016 with an edition plan of around 60 outstanding volumes. And it looks like we will finish almost exactly on time.”

Hoffmann: I am filled with gratitude for this task that I have been able to take on. However, I am astounded and also disappointed that this editorial achievement is barely noticed—even in anthroposophical circles. This is evident from the sales figures, for example. It is very sobering that much of what has been published in recent years has hardly been received. But ultimately, we have always said to ourselves, tongue in cheek and rather immodestly: we are working for eternity. All these CW [GA] volumes that we are now publishing will be the benchmark for the study of Steiner in the coming decades and centuries. Books have a long half-life, and in this respect, we take comfort in the fact that they are not immediately received. Rudolf Steiner’s complete works simply have to be available.

Bohlen: I see it that way too, and that is indeed the magic. Great works are studied over centuries. I sometimes have the impression that research into Rudolf Steiner is just beginning in some areas. Much of it has been covered over by traditions and legends that prevent people from engaging with Steiner or being surprised by him.

Hoffmann: We want to present the material in the form of the Collected Works in order to enable an open and unbiased examination of Rudolf Steiner without any preconceived interpretations. This is what we hope to have done and continue to do.

That’s a good bridge over to Angelika Schmitt and Philip Kovce. What is your relationship to the archive?

Angelika Schmitt: I come from the field of anthroposophy research and did my doctorate on Andrei Bely, a Russian symbolist and esoteric student of Rudolf Steiner—on his major work of cultural philosophy, which was long thought to be lost and was inspired by Steiner’s thoughts. I was also interested in Bely’s drawings of meditation. And that led me to the Rudolf Steiner Archive a few years ago because some of them are here. Before that, another activity had already brought me to the archive—I was working on a project for inter-religious dialogue at the Institute for Waldorf Education [Institut für Waldorfpädagogik] in Mannheim and looked at the books on the various religious streams that Steiner had in his private library, how intensively he studied them, and what interested him especially. So, I already knew about the archive when I was made aware of the job opening, and I seized the opportunity and applied. And now I am very happy to be able to work here in a team with Philip Kovce.

Philip Kovce: We had already met at the Rudolf Steiner Research Days [Forschungstagen], a colloquium that I helped organize for a few years. The Research Days were a regular guest at the Rudolf Steiner Archive, so, I already knew the archive as a venue for events. In 2011, I did research on Steiner’s “Ethics of Speaking,” also in the archive. And the first booklet I edited in 2014 at Rudolf Steiner Verlag [Publishing House] is dedicated to Steiner’s concept of freedom: Stichwort Freiheit [Keyword: Freedom]. Without electronic access to the Collected Works, this would hardly have been possible. In short: venue space, research center, digital service provider—it seems to me that, in the past, I had already experienced the future prospects of the Rudolf Steiner Archive. They will play an even greater role when the publication of the Collected Works, which has shaped its identity to date, is completed. Then, it will be a matter of finding a new sense of ourselves.

“In my youth, I was fascinated by one of Steiner’s thoughts: that the human being is a thought conceived by the hierarchies of the cosmos. At the time, it seemed very grand and powerful and almost incomprehensible to me. Over the years, it has become more and more filled with content and I have discovered that Steiner’s esoteric work is nothing other than the spelling out of this thought.”

This public access is part of the archive’s self-image.

Bohlen: What is now in development, for example, is a permanent exhibition on the life and work of Rudolf Steiner, as well as the development of a research archive, including digital material that can be accessed without having to come to the archive. Or one can study the original documents on-site, which requires not only a well-organized archive but also one that is well-indexed.

Hoffmann: Public access to the archives has existed since the reading room was set up in 2013. No credentials are required to use the archives. Everyone adhering to the rules of use is very welcome. For many in the anthroposophical movement, it has not been so easy to hear that Rudolf Steiner’s work belongs to the public. Accordingly, the Rudolf Steiner Estate Administration, which maintains the archive and publishes the Collected Works, was converted from an association into a non-profit foundation in 2015. Legally, too, Steiner’s estate no longer belongs to anyone but only to itself and is available to the world.

What does this mean for archiving?

Bohlen: Angelika Schmitt and Philip Kovce will initially complete the Collected Works. When David Marc Hoffmann leaves at the end of March 2025, the project will continue at least until the end of 2025. The next task is to thoroughly catalogue the archive holdings. We have to admit to ourselves that so far, we have mainly been an editorial archive. The main focus has been on publishing the materials as part of the Collected Works rather than on systematically cataloging them and making them accessible to others. Naturally, anyone can come to the archive today to view archival materials, attend exhibitions and tours, or use the reading room, which is equipped with an excellent reference library. But, in the future, the new focus will be a research and exhibition archive while maintaining its editorial expertise because new editions and new revisions are, of course, still in demand.

Permanent exhibition and digitization of the archives: how can we form an image of these?

Hoffmann: People are always talking about digitization. But first, cataloging, inventory, and professional archiving are needed. As Cornelius Bohlen has already said, the archive has so far been primarily an editorial archive. Although the archive is very well organized, it is not cataloged and inventoried well enough to be made available to the public via a public portal. This will be a task for my successors: the inventory and partial digitization of the archive. Inventory means taking stock: notebooks and notes, manuscripts, letters—around 3,000 from Steiner and 25,000 to him. Making all of this accessible and then digitizing the most important parts of it to create a kind of digital reading room; this is one of the challenges of the future. It will take years to accomplish.

What are you doing in your induction period?

Schmitt: Of course, we first want to get to know the whole organization—the various areas of work, how the editing works, how archiving is done. It’s important to get an overview so that the material holdings can be transferred to a digital database in a way that makes sense. In addition, the focus is on the centenary of Steiner’s death. There are many events planned.

Kovce: I can simply concur with all that.

“Venue, research center, digital service provider—these are the future prospects of the Rudolf Steiner Archives.”

David, before your work at the Rudolf Steiner Archive, you managed the Basel-based Schwabe Verlag, the world’s oldest publishing house, founded in 1488. Your predecessor, Walter Kugler, is anchored in the European art world. Philip, as an author, economist, philosopher, and moderator, you are networked with the German-speaking cultural world. Is this cosmopolitanism part of the archive’s identity?

Kovce: First, I would say that this cosmopolitanism is in line with Rudolf Steiner’s work. Whether as a philosopher, theosophist, or anthroposophist, basically, Steiner was constantly fleeing from the ivory tower—an “anti-occult” scientist who, even in intimate ritual or meditative contexts, was always concerned with the big picture as a public issue. Steiner owes his cultural effectiveness to this cosmopolitanism. He was not content with merely offering new pedagogical, ecological, or therapeutic perspectives, but he established a new art of education, a new art of agriculture, and a new art of healing. In this sense, the Rudolf Steiner Archive does not guard treasures that are sufficient in themselves but rather treasure maps that point the way out into the world. I find this form of open-mindedness or selflessness of the archive especially exciting.

It sounds as if you didn’t have to think twice about taking on the role of director of the Rudolf Steiner Archive.

Hoffmann: That he mustn’t ever do!

Bohlen: Though, in this case, he did: he thought about it for some time . . .

Kovce: . . . and then accepted.

Bohlen: This was a surprising process for us because originally, we hadn’t intended to form a leadership team at all. That only became clear during the application process, when we had these two attractive candidates. With them, we found a constellation that we hadn’t been looking for! That’s the luck of the unexpected, which we have to be open to.

Again and again, for example, in the much-acclaimed Sternstunde Philosophie [Star-time Philosophy] on Swiss television, you, David, as head of the archive, are asked to join a conversation. Is the archive seen as a point of contact for anthroposophy?

Hoffmann: Yes, absolutely. We are an outward-looking institution. We research, publish, and also loan out many things, such as Steiner’s blackboard drawing, to museums worldwide. Some of the requests that come to the Goetheanum are forwarded to us. We are an information center. But, we don’t claim interpretive sovereignty. We don’t interpret Steiner’s work—we present it. Whenever possible, we refer questions of content back to the questioners themselves. If you want me to say what a particular passage in Steiner’s work means, then I can only say that this is not our task, but each individual’s task.

Bohlen: With that, of course, there are corrections that need to be made. This has been an important task ever since I’ve known the archive: to check things that Rudolf Steiner is said to have said or done and which sometimes haunt the world as, to use the modern term, fake news.

One such rumor is that Steiner banned soccer at Waldorf schools.

Bohlen: Yes, for example. We cannot, of course, prove that Steiner never said such a thing, but we can indicate that there is nothing to support such a statement.

Hoffmann: In this sense, we are often consulted for fact-checking and then pass on factual information.

Bohlen: Admittedly, the question is how to finance such a service. We have an obligation to the public but also to the anthroposophical movement to be able to provide information and to be an information center. Steiner’s image is distorted by opponents and critics but also by those who revere him and who propagate images of Steiner that may be interesting but are often not true. Helping to clarify this is an important but economically unappreciated business.

Hoffmann: All the myths! We are said to withhold Ahriman’s date of birth, which is said to be in one of Steiner’s notebooks. This accusation appalled me. It is neither our mission nor our practice to withhold anything. On the contrary: we make all archive material accessible and have therefore indexed all 638 of Steiner’s notebooks page by page. In several all-day sessions, we have gone through all the notebooks, making notes and indexes. And so now we can find all the names and all the data in a database. That was a huge undertaking.

Bohlen: You couldn’t find Ahriman’s birthday?

Hoffmann: No. As I said, unfortunately, alongside all the goodwill, there is also repeated suspicion. We work as transparently as possible. We document where, how, and why we make editorial changes. We present all the materials and provide the archive locations. Anyone can check this. And yet there are still nasty insinuations. That feels bitter and disappointing. We are all the more grateful for the many expressions of approval. There are people who write to me personally, thanking us warmly for our work and enclosing 50,000 francs in cash—as happened some time ago. Others pay 20 francs every month, for years. Still others have sold their parents’ house and donated the proceeds to us. It’s not only the money for our work that is important but also the encouragement that comes from it. It is a form of recognition of the work we do, a recognition of the work of Rudolf Steiner.

“This has been an important task ever since I’ve known the archive: to check things that Rudolf Steiner is said to have said or done, and which sometimes haunt the world as, to use the modern term, fake news.”

Angelika and Philip, is there a sentence or thought of Steiner’s that is especially important to you or that has shaped you personally?

Schmitt: In my youth, I was fascinated by one of Steiner’s thoughts: that the human being is a thought conceived by the hierarchies of the cosmos. At the time, it seemed very grand and powerful and almost incomprehensible to me. Over the years, it has become more and more filled with content, and I have discovered that Steiner’s esoteric work is nothing other than the spelling out of this thought. But then I became increasingly interested in whether and where this idea can be found in other authors and in other contexts. And what forms it takes there, in which words and pictures it casts there. And who knows, perhaps the cosmos has, indeed, led us both here and entrusted us with the honorable task of shaping the future of the Rudolf Steiner Archive.

Kovce: Who knows? Perhaps, it is we ourselves who have led us here. In any case, the self-guidance of destiny seems to me to be no less a grand thought in Steiner’s cosmos of ideas. I was enthusiastic early on about Steiner’s early work and its blazing fire of freedom. Since then, I’ve wondered to what extent the later work is a literal translation of this impulse of freedom. It may certainly be the case that Steiner, in certain discourses and initiatives, falls short of our or his own expectations of freedom today. Nevertheless, I see his tireless commitment as being precisely for this—for the free, self-determined human being and a world that suits such a being. Proceeding from this, I repeatedly ask myself: What can I do here? What can I do now in the light of freedom?

What kind of support would you like?

Schmitt: An honest interest in and passion for the work of Rudolf Steiner in order to advance research. Academic research into Steiner and anthroposophy is still in its infancy, while research within anthroposophy is hardly noticed in the world or is not taken seriously. Now that the Collected Works will soon be completed, research into Steiner can really begin! There is a lot to be done: providing scholarships that enable people to do research here on site; correcting the distortions and half-truths circulating in the public sphere in order to leave behind false or narrow pictures of Steiner; creating an atmosphere in which a calm exchange about the work of Rudolf Steiner is possible, in which different positions and perspectives can enrich and fertilize each other.

Kovce: There is nothing more for me to add for the time being.

Translation Joshua Kelberman

Photos from the conversation Wolfgang Held