Laughter is an experience the spirit makes, and there has been a work group for clowns at the Section for the Performing Arts since September 2021. Who should know best about humor than those, whose vocation is to make people laugh. Gilda Bartel inquired about their work and their thoughts.

What happens when laughing, that is, in your workshops?

Catherine Bryden, alias Carrottini Milton Berle said: «Laughter is an instant vacation.» Angela Hopkins asks in the movie ‹Annika›, «When was the last time you laughed? A really good laugh?» So when was it?

During clowning theater workshops we laugh a lot. Sometimes we laugh so much that everything hurts, and we gasp for air during uncontrollable fits of laughter. We chuckle, giggle, grin and smile – a knowing or curious or awkward smile. The most moving thing is when someone bursts out laughing and we can see that the person has no idea why the laughter has taken over their whole nature. Then we laugh even more. Humor is a gift. During the initial warm-up exercises of a workshop, as a moderator, I consciously and actively steer participants away from being funny or making others laugh. The word ‹clown› pressures people to be silly or foolish. It contains images of slapstick tricks and big shoes. Though this does not apply to theater clowns. Our clowns can sometimes be silly, but this is not intentional. Laughter during a workshop cannot be planned or arranged, but we can offer room to provide the tone and mood for warm and loving laughter. Since there is no room for sarcasm in our clown world, it is not our intention to cultivate cold or intellectual laughter. When we expect laughter or try to be funny, we invite an uncomfortable silence into the room.

The beauty of the relationship between humor and laughter is its intangibility and unpredictability. When people laugh, I experience movement, openness and ease. When I laugh or watch people laugh, I feel deep levels of ease and connection. Columnist Fred Dennehy goes into more detail in his column ‹Laughing and Weeping›.1 Rudolf Steiner recognized – as did Socrates in regard to comedy and tragedy – an intimate relationship between laughter and weeping. Laughter usually manifests as a series of staccato exhalations followed by a long inhalation. Weeping is the opposite – a series of discontinuos inhalations followed by a long sigh. These processes are expressions of what Steiner observed as the astral body – the bearer of emotions such as joy and pain, sorrow, terror and amazement. While experiencing laughter, the astral body – to use Steiner’s term – withdraws from the physical body and expands. It expresses «inner liberation» of the spirit. In regard to weeping, the opposite happens. It «pushes down» on the physical body and contracts in a gesture of «inner strengthening». Steiner’s account points us to a perhaps surprising realization: that laughter is an experience the spirit makes. When I watch transformations in people who have laughed, I have no doubt about it.

What is the connection between a child’s innocence and that of a clown?

Sebastian Jüngel, alias Topolino It peeks out, the red nose. Curious. Behind it: the whole nature of a clown. Impartial, naive, eager to discover. It stumbles over a chair. Never mind: second try. Again it bumps the chair, again and again, until the clown sets the chair aside. Though as soon as it gets to where the chair was before, it stumbles.

Impartial? A clown is both: ignorant and knowledgable. Thus it resembles a child. Both encounter the world openly, with interest, empathetically. They play with what they encounter – and that means: they learn by engaging with an object or with a situation. Or they endure what is unchangeable by reinterpreting it: something unpleasant becomes a pleasure.

Naive? A child is born with an impulse of will. It brings with it what it wants to live and achieve, and strives forward. A clown also finds a way to deal with everything – and quite skillfully; whoever embodies a clown knows exactly what is coming, even if it is experienced authentically as something new in that moment. Doesn’t this remind you of the life preview that Rudolf Steiner once mentioned?

Eager to explore? Greater knowledge allows children to endure many things, they carry on; a clown is able to rise above the mortification of failure. This distancing leads to a change in perspective. The view from the outside leads to humor by taking what has happened in its relativity, in its shift and as a starting point for something new.

Edith Maryon and Rudolf Steiner depicted this asymmetrically elevated aspect, without being grand, in their wooden sculpture ‹The Representative of Humanity› as a rock creature on the upper left. In clowns, I see an expression of world humor – just as a swarm of bees (world humor) appears in many individual bees (clowns). The whole is more than the single bee, but without it it would not be on earth; the bee lives as itself, but is connected with the swarm.

Why do clowns make us laugh?

Carrottini When we laugh with clowns and we as clowns can let go, we free ourselves and open our hearts. We recognize truths and create internal space. We are touched by a wave of authenticity, the problems, the embarrassments, the confusion, the challenge of being fully human. When we laugh, we connect – with ourselves, with other people, with a moment, with a surprise. We laugh when we recognize the contradiction that exists between what we long for, our dreams, hopes and desires and what is happening or who we are at that moment. Human beings are full of perfect contradictions.

Clowns celebrate this blend. In clowning, this incongruity is wrapped in love so that we laugh more deeply and sincerely. Not about the clown, but with the clown. We laugh at the absurd truths of what it means to be a human being. A clown has a sparkle in its eyes, which allows the audience to be part of the great fun the clown is having. Contact with the audience reveals the truth about what a clown is experiencing in the performance, and often unintentionally reveals something about the struggle and absurdity of being human. We don’t practice being funny in a workshop. In fact, it’s painful and uncomfortable to watch someone try to be funny. A clown is born in authenticity, a deep love and loyalty to itself and the situation. We practice being true to our feelings, ourselves, our dreams, and our desires, perhaps for our higher greater self. A clown approaches problems not with humor, but by noticing what others are missing. It learns to be very present in its perceptions. It is open to the paradox of what it perceives without trying to judge it. Paradox, according to the Oxford English Dictionary, can be defined as an apparently absurd or self-contradictory statement or proposition which may actually be true. The best place for a clown is where severe difficulties and detriments are present. The harder, the darker, the colder, the better for the clown. For it knows that is where the paradox lies, the unexpected, the surprise. That is where warmth and light is concealed in equivalent power!

What do clowning and the anthroposophical path of training have in common?

Debora Kleinmann, alias Libella Amazement, awe, impartiality, devotion and dedication, these are all attitudes that young children still have unconsciously and that enable them to find their way into life and to ‹comprehend› the world. They lead children to a relationship and understanding between self and world. If we as adults want to set out on a clown’s path, it is precisely these attitudes of the soul that are absolutely necessary if authentic play is to emerge. This is the only way ‹the child› in the other person can be touched in an encounter with a counterpart (be this in an open setting during a clown visit or with an audience). Then, through the feeling, the soul recognizes itself through the clown. In this contact and encounter, a loving, accepting smile can emerge at one’s own human qualities with all its misfortunes and faults. Unlike children, however, it is possible for adults, through thier I-ability, to surrender to play and at the same time to look at themselves from the outside – this creates a moment of humor … and ultimately acceptance in love!

Another topic in regard to both paths is dealing with emptiness. In clowning this requires and means going into an empty play space without program and planning, all senses and the whole soul open, in order to then act situationally and intuitively in the now (for example during clown visits in hospitals): ‹Providing room for nothingness!› Concerning current events another thought becomes topical for me: the meaning of these inner attitudes in connection with the development of thinking! In ‹The World of the Senses and the World of the Spirit› (GA 134, 1st lecture) Rudolf Steiner describes how today’s scientific thinking certainly leads to logically correct results, but this thinking does not necessarily represent reality. If the path to thinking that is true to reality is to be found, four inner attitudes must be placed alongside this thinking. «Amazement, veneration, harmony full of wisdom with world phenomena, surrender to the course of the world, these are the stages which we have to go through and which must always accompany thinking, which must never leave thinking – otherwise thinking results in something that is merely correct, not true.»2 The fundamental attitudes listed here are thus all prerequisites for inner development.

Through my work as a clown, the terms mentioned here have gained considerably in vividness and comprehensibility for me over the years. They have become more tangible. A repertoire of exercises has emerged, which I believe would also be an enrichment for ‹non-clowns›. I would therefore like to elaborate and offer a workshop on this topic, based on ‹How to gain insights into higher worlds?›, complemented with practical exercises and experiences from the field of clowning. Has your interest and curiosity been aroused? Then please contact me!

Clowns live with the wisdom of the imperfect. Does humor help to stay flexible, not to become too firm?

Robert McNeer, alias Cosmonaut Bob ‹Mind the Gap› – this phrase, which I learned during a subway ride in London, sums up clowns’ wisdom beautifully. For clowns, as for small children, nothing is too small to consider. The gap that needs to be minded may include many things: the gap between my intentions and my abilities – the extent of my imperfections, which I hide with great energy in my daily life, but in which my clown revels; or the gap between my material life and my fantasy life – when I imagine my chair turning into a rocket ship or my desk turning into a dinosaur – this too is a moment I would cover up or ignore in my daily life, but which my clown celebrates because it knows that this is the wisdom of metaphor, the lifeblood of poetry. Though maybe it’s the gap that clowns pay the most attention to, the gap between the you and me. This is the gap that often troubles us the most in our daily lives: the domain of misunderstanding, double-headed monstrosity, judgment and self-judgment. It is precisely this gap that clowns bridge with humor, depending on whether they are elegant or not. None of us is perfect, and the world we live in is certainly not perfect, but clowns have the ability to optimistically navigate multiple often contradictory worlds without having to combine them into a single reality. This is the wisdom of the imperfect: the paradoxical knowledge of not knowing, the encounter of clown, child and wise man. Translation: Simone Stadlbacher

More about the four clowns: Debora Kleinmann, Catherine Bryden, Robert McNeer and Sebastian Jüngel

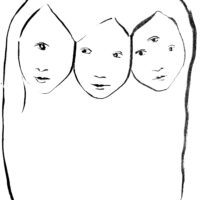

Drawings by Estella Mare

Footnotes

- Spiritworking/featured columnist

- Rudolf Steiner, The World of the Senses and the World of the Spirit. GA 134, 1st lecture.