Twenty-one years ago, Maaianne Knuth founded the learning village ‹Kufunda› in Simbabwe, on her mother’s farmland. Her impulse was to reconnect the people with their roots, which were split by colonialism. One of our Editors, Gilda Bartel was there in October. The first fruit from this visit: a conversation about black-and-white thinking and a white man, whose teachings weave the people together in a new way.

Gilda Bartel: Maaianne, you are half white, half black. Your husband is white. Nowadays we have a lot of questions about white privilege, postcolonialism, and the decolonization of thinking in Europe and America. What do you think is white privilege and what responsibility does it put on us? As we are in Africa we could speak about the African situation, but it’s a question for all indigenous people. So how do you experience it in Zimbabwe and in South Africa?

Maaianne Knuth: It’s not such a simple question. Even though I’m half white, half black, I consider myself much more of color than white. And at the same time, I’m very conscious that here I have a lot of privilege that does come out of my white background or at least my level of education as well. I think there’s a story about what it means to be white in the world that’s slowly being dismantled. But that story lives in the space between us and within us. And so what I see here and probably in myself as well, is an unconscious belief around white superiority. On the surface, there is a stated belief around equality. And then every now and then moments appear like: ‹Oh, wait a minute, what just happened there? What does that show us about how we think about white versus black?› I think that happens to every person, regardless of white or black. And there’s deep inner work to do for real reclamation. I’m on that journey and I have a real sense that black is powerful, potent, and beautiful, but there is a real need to stand up in it. And then the noticing: where the white is, is privilege, simply by virtue of unconsciousness. In the history of this country, in many countries, whites have been taken by colonizers, and the whites had been and are now richer. And so it lives on. Of course, there’s been some redistribution that’s been attempted here. But I actually feel like the thing that sustains it, is the unconscious assumptions and beliefs that live on. That is why an education that’s really about creativity, imagination, and critical thinking is so important so that children grow up without that same old ballast.

GB: I even experienced that on my own when I came here: when I first attended one of the workshops you offer here, I expected it in one way or another to be on a lower level than white peoples workshops would be, only because the surrounding is not that modern concerning to material matters. When I saw the high quality you do with the youth workshop and my own son telling you afterward: ‹We need these workshops in Europe as well›, I realized. Why did I expect it to be less? I don’t feel ashamed now, because it’s a waking up and I mention it as an example of what you probably mean. So what assumptions live in the Zimbabwean people towards me and my being white?

MK: I think very similar ones. There’s an assumption that we are less. And is it white/black or is it educated/not educated? I don’t think anyone here in Kufunda has a university degree except for myself. And many haven’t finished high school. It’s a particular kind of segment of a socioeconomic grouping. ‹Colour› is part of that. But people are beginning to ask, as we go out and do our work in communities: ‹Can you come to our communities? We’ve heard the work you’re doing is really incredible›. So the ‹communiversity team› of Kufunda is beginning to wake up to the values we’re bringing. We knew it was valuable, but now there’s an external affirmation. So we are just beginning this process of harvesting: what is it we do and how? So that we can begin to stand behind our own knowledge more strongly. I also think there’s this whole system of how it’s meant to be, that comes out of a white system. Is it white or is it just eurocentric? Eurocentric is primarily why. If we are to be seen to be important, we have to fit in there. So the reclamation comes first, like throwing that away and rooting in our lived experience and beginning to honor and celebrate that. Then beginning to convey it. It is about different narratives. And they are not new, but they just haven’t been shared beyond.

So my answer to your question is: come and assume the best, come and meet people in their dignity, and be curious about their gifts. It doesn’t matter how much education, how rich or poor. But that’s true for the whole of humanity, right? But it really hasn’t happened in Africa. 99% of the encounters look at what people here need with an assumption of backwardness and poverty. It is strengthening the belief and the insecurity that may be still here. So to be met really as equals and then also for us to meet you as equals. There’s also deep healing for the white person in that encounter.

GB: When you put a category to someone, you always categorize yourself at the same time, but you don’t realize it. So you are also limiting yourself. In my experiences and encounters with Africa, I used to give money to African friends because I have a better income. But that’s not what you first would request?

MK: That’s not my first, no. Because if you give money out of a poor, then I have a sense it doesn’t have a good energy. We need money, absolutely. Kufunda has always been primarily funded through friendship money. We get some small foundations, but actually, our lifeblood since our inception has been friends. I am just in process of writing to friends to say ‹It’s time to come back and step into support some more›. But more out of a wanting to support something that’s alive and flourishing and I would say, of the future. I do think that more money needs to flow from north to south, but in a completely different way and tone, which comes out of human relationships, respect, dignity, equality, and love. All of our work is always emerging. We’ve got a vision and plans, but we work with what’s right here. And so a lot of the bigger foundations, they want you to give them the specific grid of what you’re going to do and how you’re going to get from here to there, with very little flexibility. And so it’s like you freeze an idea in a moment of time and then you have to stick to it. But time is continuing to move. It’s like you’re forcing some past mental model into the future rather than engaging and dancing with the present. And that’s what money can do, that’s free and with respect and love and equality. It’s alive still. The other money can be deadening.

GB: But do Zimbabweans and even the South Africans who have black or coloured origin, have any claim to the whites?

MK: It really depends on where you are. My sense is that’s quite strong – I hesitate to speak to that fully – in South Africa, for example. We did a workshop here (at Kufunda) a few years ago where these different issues, polarities, and places of conflict showed up. The hottest ones were allowed to come. And the race piece didn’t show up until the very very very end. But before that was the intra-tribal conflicts. There were men, women, there were the youth, and the older generation. Some of those conflicts were much more like the entrenchment of party politics. Because the black government right now is really not that different than the colonial government. They took over a system that worked and they’ve continued it. So the angry activists in Zimbabwe today are really turned towards the government more than the colonizers. And when you then go a little bit deeper, that’s where it is. But that’s just from my experience. It’s not the most forefront at the moment here in Zimbabwe.

GB: Sometimes when a white person thinks about that, it also leaves out that people in Zimbabwe, in South Africa, in Ethiopia, wherever, have their lives. It’s not like they have nothing. They have their culture, which was pushed down and now awakens again. But they had their societies, their culture, their religions, their beliefs, and their rituals. So if I think about this in my whiteness, being ashamed that white people did, I could miss that hard fact. And maybe they don’t bother too much about the whites. Of course, it’s different in South Africa, because of the Apartheid.

MK: My recent experience from Cape Town is that it is still strong there. You still have such clear black/white demarcation. Of course, you also have that here in Zimbabwe in some neighborhoods. But arriving in Cape Town, I was like, ‹Oh my God, this is shocking.› People are living these wonderful, comfortable, primarily white lives in certain neighborhoods. And it’s just how it is. This seems to be very little questioned. Big gaps between haves and have-nots. Financially? Yeah. So for the white person waking up in their beautiful mansion with pretty much the only black people coming into their neighborhood, being gardeners and maids. I think our responsibility here at least is to live with the question of how else it could be. A lot of people are living in deep sleep on that. And then often they don’t meet the gardener and the maid as a human being, but as a service provider. Michaela Glöckler was saying: «The only reason these systems are still there, is because we accept them.» So I guess the question for me is what is past acceptance?

We as Kufunda have made a choice. We cannot and will not fight against. Fighting against would be such a waste of energy. And blessings on all who make that choice. But I think often in fighting something, we make it stronger. But we could build something that has the quality, taste, and gesture of what might be possible to create. That’s what we’re trying. Living into the future we wish to see, rather than fighting against the past which we wish to transform. And it’s a journey.

GB: So my question – in what responsibility does it put us as whites towards black people? – you would answer: ‹take responsibility if you feel it towards somebody, who you want to support›? So you would say there is nothing to be generalized on this? If I want to support Sikthiwe(one of the facilitators of Kufunda), I support her. And then I don’t support her out of my whiteness and her blackness, out of the race, but because she is in the things she wants to do. Do you mean it this way?

MK: I think at some level it is about the individuals. But I also feel like it is about shifting my inner assumptions about people of color. It is lifelong work that I can meet someone without judgment and I can meet them assuming the best. But for me, there’s a big healing that’s needed between whites and persons of color for both sides. You can feel when you are being met like that the other is a bit above you in their mind and assumptions. It also happens with people with master’s degrees coming and meeting some of the Kufundees. So how do we meet each other as human beings? For me, that’s the crux. I think the next level for Kufunda is what it looks like to organize this more effectively. So if it’s just supporting Sithktiwe, you would miss this bigger work we are trying to do. I would say supporting Sikthiwe by supporting Kufunda is a collective seeking to do something and making a choice to trust.

GB: That would mean complete healing. Because if I want to look at my assumptions about colored people and change something in there, I will change in general with effects on all human beings. And it’s the opportunity we have now: to overcome these judgemental ways of looking at people, either in ways of how highly educated they are or of how much money they have or of gender or in terms of race.

MK: What we talk about is huge. Probably generations away. But everything starts now.

GB: It would be good to do that together instead of white people telling white people and other people how to do it. Rather starting the encounter: ‹What is my assumption about you? Can you tell me what you feel about that?› And then developing new things together instead of developing in my own mind, how it should be. If you put it in a community, it is more secure to stay honest and dignified, because I cannot fall so much into my own imagination. In the encounter, the other one will just tell me when I misunderstood.

MK: I’ve seen a moment where well-intentioned white people having so many blind spots and a black woman saying: «It’s not my job to educate you.» So I think there are places and spaces where it is important when women alone meet and then there’s a point where they meet with the men. And men alone meet, and then they meet with the women. And black people alone meet, and then they meet with whites. And white alone. All these categories are part of us. But there is something about ‹just as us› that is different. I see the difference in some of our young women programme when there are white young women in the group and when not. There’s a playing to something and it’s all these unconscious stories. I’m not going to send the white woman away and say ‹you can’t join›. But sometimes it’s actually good that it’s just the local women together. Part of my future vision for Kufunda has to do with this healing and I’m still dreaming into it. It makes sense to me, because I have my white father and my black mother.

GB: Maybe then we go to this Anthroposophy question. It’s a white man’s anthroposophy, actually. What do you think Anthroposophy can bring in here and how can it connect with the African consciousness? What do you hope to come out of it?

MK: In many ways, it would be much easier if Steiner was some West African Guru or an Indian. But he isn’t.

GB: But you can handle him as a spiritual teacher like there are different spiritual teachers in the world.

MK: A few years ago it became really clear to me that he is a core teacher to me. We started doing Waldorf and Biodynamics and enter into these more practical applications on Anthroposophy. And only then did we start doing study as a village. The first years of study didn’t need all the concepts. ‹The Seven Conditions of the Esoteric Student› are actually conditions for a good life for anyone. We did some of the nature observation work and some of the other text from ‹Knowledge of Higher Worlds› that really are deeply profound and quite simple. What I find with Steiner – because I’ve also tried reading texts of people who’ve written about what he says – was that something is transmitted when we read the direct text that is harder to access when we read secondhand. And so I don’t understand it all, but I have a sense that something from the spiritual world comes right through and joins us. It’s very gentle and it’s very gradual and it’s very steady. But I have a feeling that something in all of us who are engaging with it is transforming, individually and in the relationship. For the whole period of COVID, we used to meet every morning in the circle outside and would say the social verse. And I remember thinking ‹in the mirror of each soul›. It´s these little enormous things that arise. So I don’t care that he’s white, from Austria and he lived 100 years ago. Some of what he’s bringing is very profound for us and very, people would say, very aligned with traditional culture and honoring each other and ancestral understandings. In the few texts we read about death, people were so relieved. Because the Christian church told them that it was evil to talk about your ancestors. And then Steiner, who talks about the Christ, also talks about ancestors and dead people. And it’s a science. Because the white man made the black people’s beliefs simplistic, childish, ridiculous. So actually, for another white man to come and lift it and say, there’s a science of what’s actually happening. It’s like oxygen. I see that I’m still a translator, but that doesn’t make me more than or better than anything. But I do have the European education. So I’m supporting a translation, but I’m also receiving so much. I mean compared to everyone around me, I’m so selfish. I’m so individuated to the point of really struggling with what it means to be communal. But at the same time, I’m supporting people to work more into their individuation without losing their communal. So for me, it feels like a beautiful place and opportunity. I’m so grateful my children grew up here. I see the gifts of this place in them.

GB: Something in the consciousness here, maybe in a different sphere than in the ‹intellectually awakened, brain consciousness›, connects very easily with the spiritual world. Something comes in and through. The spiritual things have a real presence here, let’s call it ‹substance›. It is not abstract. In Germany, we are thinking about it, but here it’s real and people understand through feeling, that it really matters how you think of somebody. Germans or Europeans or Whites – I don’t want to generalize, sorry – have to awaken something first to realize that it’s a real presence of spirit. But here it seems to be not just talking about it as a concept, but as something which is living. Their questions are different from questions in Europe on the same topic. So I’m curious about how do Anthroposophy and the African mindset come together?

MK: When my mother died, I started reading about what happens after we die. I never read those parts of Steiner. It was such a helpful accompaniment. It enabled me to also be with my mother in a different way. And every morning when I was with the horses, I was telling Ticha of what I’d read and what I understood. And Ticha said ‹Can we please read about these things?› And I realized there are threads of themes that are actually really important to people here that I wouldn’t have thought of bringing in. To read about what happens after you die, seems a bit of a strange study for a learning village somehow, you know? And so then we spent a few weeks on that. The Christ shows up so clearly in a lot of those texts. People hadn’t realised that Steiner writes about Christ. It is actually another form of healing, even though we’re only just beginning it. The colonial Christians cut the root system of this place. But there’s something there and through Anthroposophy, which is allowing it to be rewoven together again. The Kufundees say ‹Ah it’s just like that, and my grandmother used to say this›. They’re making connections and who knows whether Steiner would agree with what someone’s grandmother used to say. But on another level, I feel like it doesn’t really matter because these connections are being made. It’s something that was not allowed from the church and which is now being opened again. Because most Kufundees are very devout Christians. I remember some of the community women, in the beginning, were like ‹Oh my God, any bad thing would happen. Let’s pray. God will help us›. And I love that at one level, yes, we can pray and God will help us. But there’s also a little bit of a ‹weak› when I give it all to God. I don’t actually have to do anything myself. Of course, they work hard and the church is saying you’re weak, God is strong, you are sinful, God is good and you give everything to him. Anthroposophy is allowing people to have Gods. It’s not the modern agnostic view. But wakes you up in your relationship to God.

GB: If it weaves people back to their culture, what is the new thing then? Is it only about weaving back into their own culture or is there anything new coming in?

MK: No, but if I have given up on my culture and my roots and I believe that they are inferior to yours, I cannot build anything new that is of genuine value. This is my firm belief. This is what Kufunda is about. It really is about reclamation, to honor the best of what lies behind us and to step on that into the future. So it seems completely absurd, but somehow Steiner is allowing the honoring of that. What the new is, I don’t even know, but I think it has to do with the question: ‹Do we have to completely let go of everything and find our way back from individuation into community›? I know some Anthroposophists who would say: ‹The Africans are a little bit backward and they are so in the communal that they haven’t individuated yet and they have this whole journey before they can come back into a conscious community›. But I feel like Kufunda is a place where we can wake up to who we are, each one of us, in community. We don’t have to go to the extreme of losing community to wake up to who we are. And I feel like that’s part of Steiner’s and Kufunda’s impulse. And meeting Anthroposophy was like: Here’s something that can strengthen that emotion, which is the impulse of people waking up.

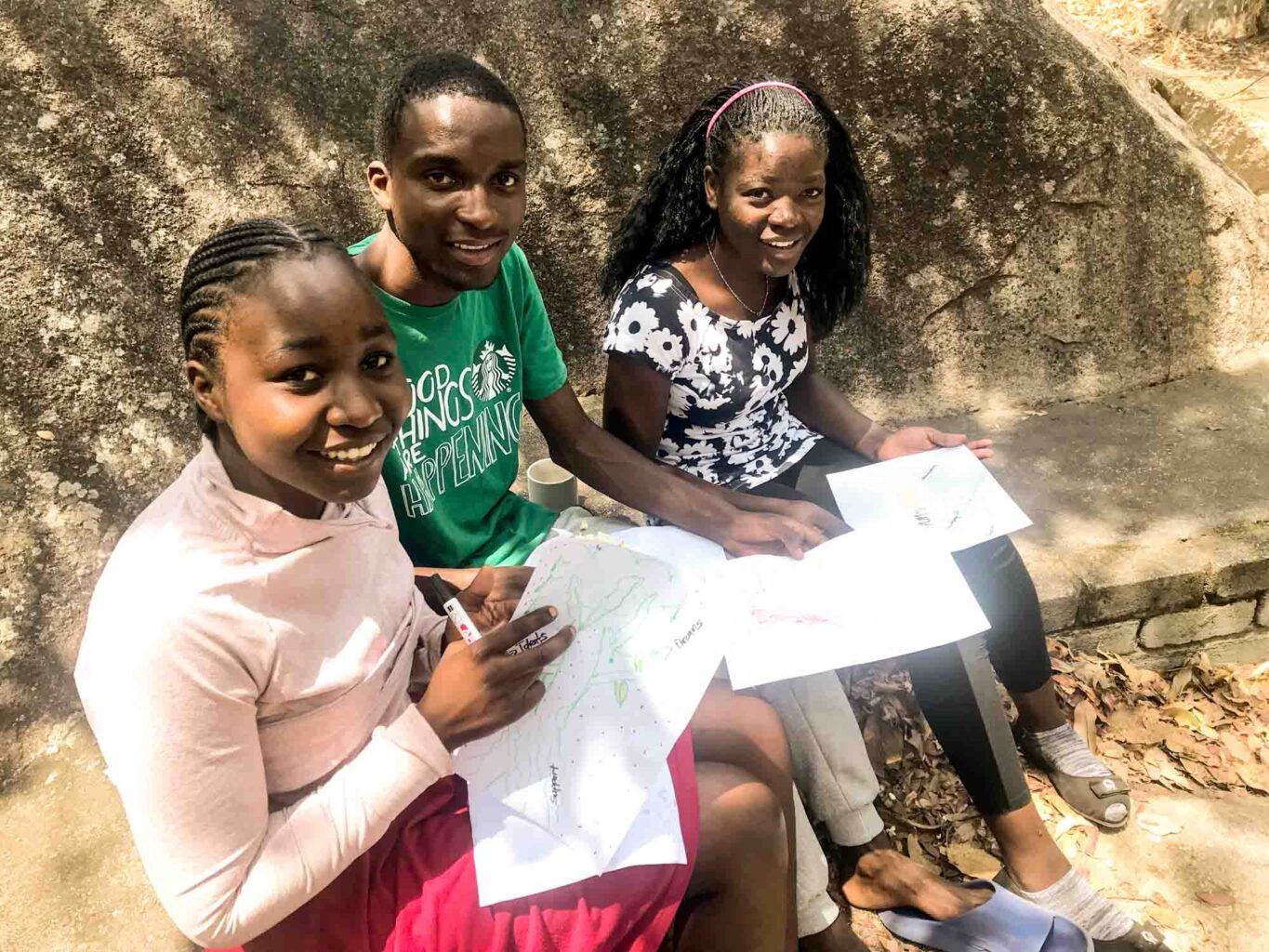

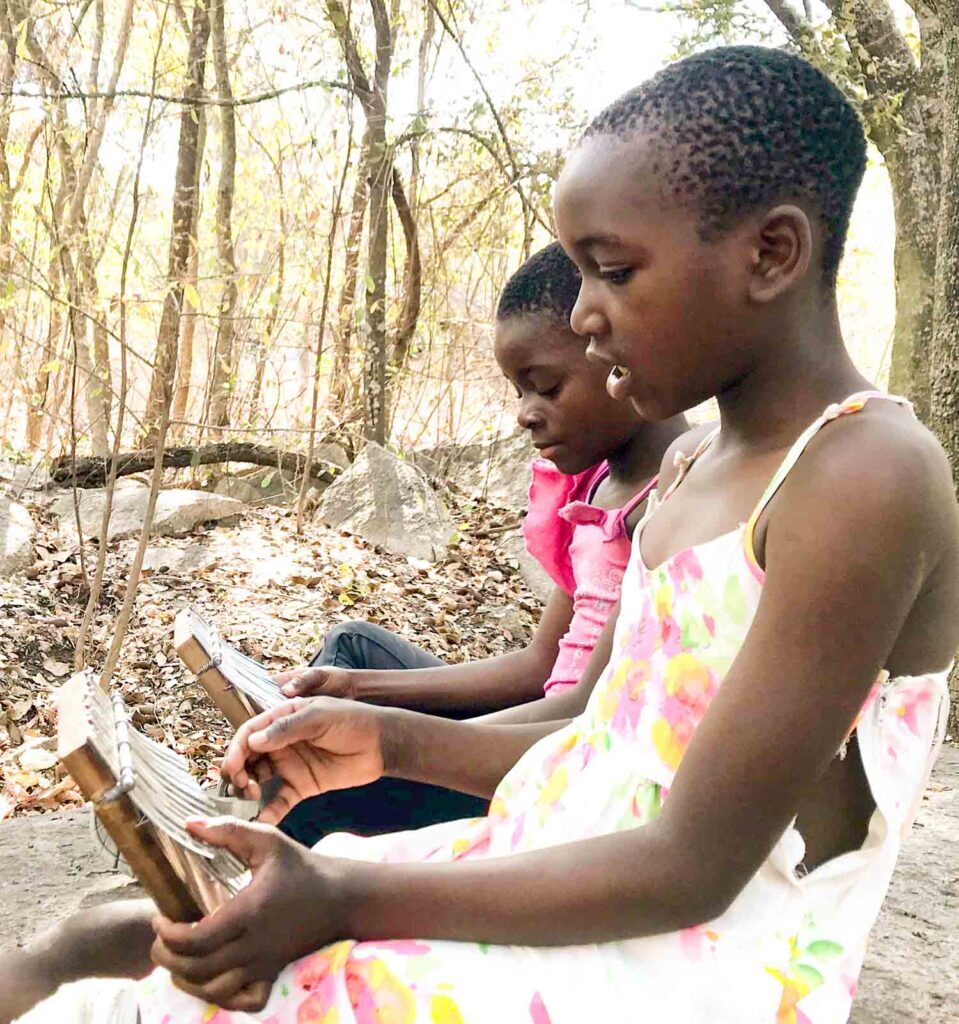

Title image: Kufunda Learning Village in Zimbabwe. Photo: Gilda Bartel

This is one of the finest, most sensitive bridge-building pieces I have ever read in Das Goetheanum. Maaianne Knuth’s initiative to found and guide Kufunda is truly heartwarming and inspiring. I also want to express praise to Gilda Bartel for her compassionate “listening” style of interviewing. I cannot end without expressing my profound admiration for Ms. Bartel’s photography. Every single piece is filled with inner luminosity and a gifted “heart-eye” for the human story within each photo. My sincere gratitude for your good work. Patricia Kaminski

Dear Gilda and Maaianne, first of all your words at the end Maaianne about Kufunda being a place where we can wake up to ourselves as individuals within community is right and I think this applies to most of Africa. Africa is the contingent where the I had the possibility of walking up to itself in community. Having said this, speaking as A White South African and I emphasise the word African here as I am not a European and this is where the arisings and this article paints a false picture of the reality that lives in our part of the world. Gilda’s questions clearly indicate a false assumption that lives in her thinking that all white people are eurocentric and not indigenous to Africa. Maaianne you were educated and grew up in Europe, I was educated and grew up in Africa. Yes I have the influence of apartheid in my childhood. It is this experience of growing up under the influence of something that is inherently untruthful and wrong that has influenced my journey towards recognising that I and my fellow human beings are each individual soul/spiritual beings and when one begins to interact with each other at this level, colour becomes a very arbitrary part of the conversation. To judge the whole of South Africa on your experience in Cape Town which is the home of many wealthy white European foreigners and the South African WASPs is painting a very false and naively of South Africa. If this is the quality of information the Goetheanum is spreading about cultures, nations and complex human social organisms then it becomes very difficult to take anything they is written in these newsletters seriously. I do hope that you will have the courage and the Conscience to engage further. Kind Regards Chandré Wertheim Aymes

I apologise for the misspellings and word replacements in my comment above but I think the gist of what I want to say is still clear and anyone who has questions is welcome to email me.

As a 4th generation white African, brought up and educated in(then)Rhodesia/(now)Zimbabwe, having lived 50 years in Zimbabwe and South Africa ond now 28 years in Sweden, I find myself echoing the truth of Chandré Wertheim Aymes’ reply. Mariannes initiative is fantastic but the picture painted/assumptions, of the above, seem unduly shallow and one dimensional, or, more kindly, naive.

Marianne, sorry, not Marianne!

Kufunda village transformed me. And when I speak of transformation I’m not speaking of just mere change. Inner inner Healing, WHOLENESS. And it’s still unfolding as I continue to live,but I’m now enjoying m(my)self , life and more connected to my purpose than before I have been to Kufunda.

Thank you Maaianne for doing your all in making your vision a reality. Which is very embracing and accommodating of other’s visions too. Namaste.

Chandre Wertheim Aymes comment is correct about the quality of information das Goetheanum is spreading about cultures etc. In that intervieuw .