The fact that all living beings, from humans to single-celled organisms, share not only the earth but also its life and health lies at the heart of the idea of ‘One Health.’ Over three days, almost 100 interested people met for the Medical Section’s research conference.

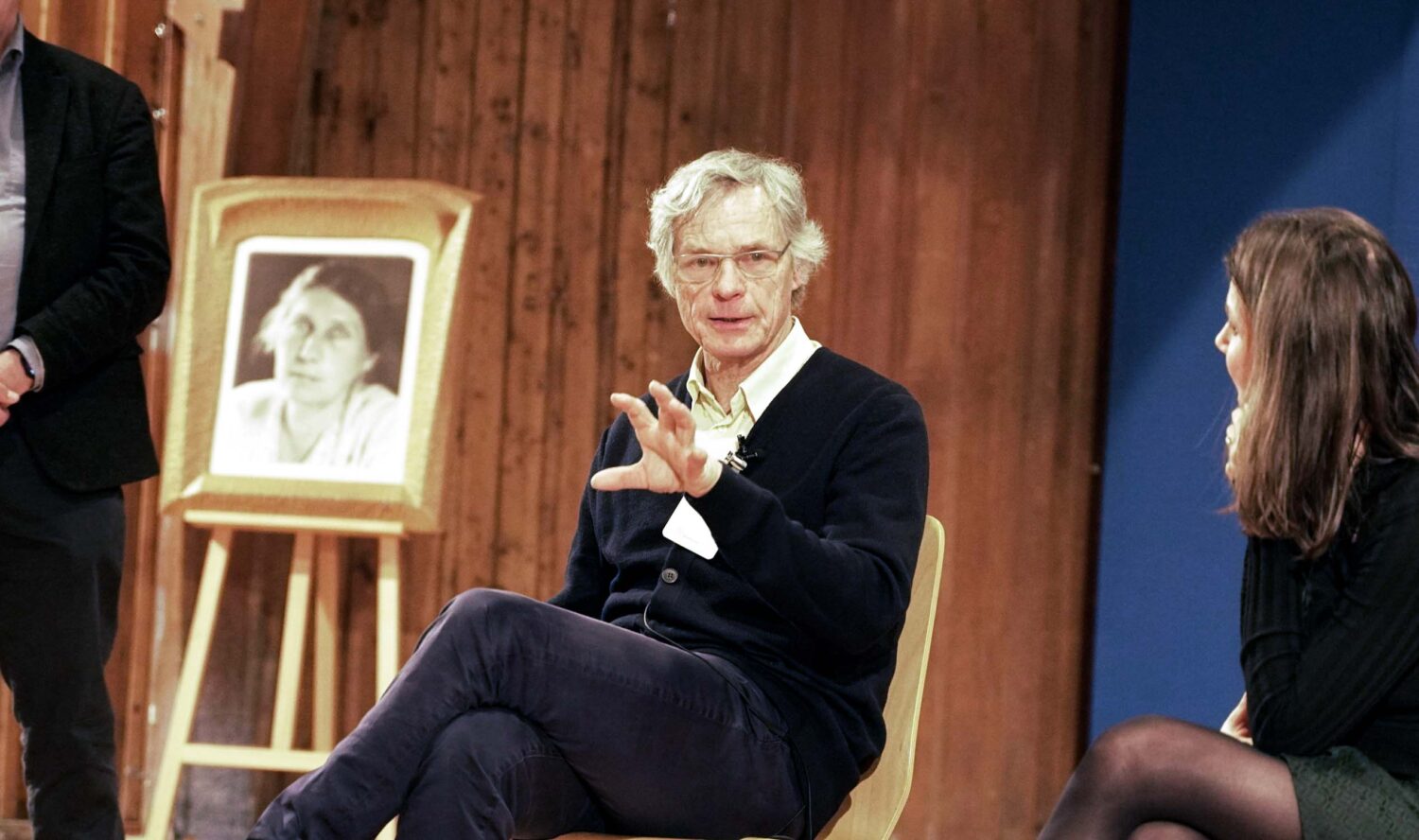

Studying and addressing life – this was the subheading of this year’s meeting of the Medical Section. Georg Soldner from the Goetheanum and Erik W Baars from the Louis Bolk Institute and professor at Leiden University led the three-day gathering. It was a Dutch-German-Swiss bridge-building event, not only with regard to the two people in charge but also because many of the participants also came from the two countries. One of the things about the Netherlands is that it is probably the most global nation in Europe. Wherever you are in the world, you hear Dutch voices. This breadth was also reflected in the number of the 17(!) contributors. Like a dance, the presentations revolved around the mystery and apparent inscrutability of life, yet always managing to jump into the middle and thus create an anchor, a point of reference. Annick de Witt from Utrecht lit such a beacon. She reported on her research, according to which four worldviews determine a person’s own compass.

But before that, Georg Soldner opened the conference. In a few brief sentences, he outlined the question: “Human thinking has consequences. We live with the consequences of our thinking. It has led us into crisis: an ecological crisis and a health crisis — the consequence of 500 years of thinking and acting. We are responsible, and we ask: How can we take care of the health of people, but also of domestic animals, wildlife, of life on our planet?” According to Baars, modern thinking had divided the world; under the concept of One Health, it was being brought back together. He called to mind that eleven Sections are active at the Goetheanum, making possible what One Health calls for – the conversation between disciplines, the conversation between art and science, between academic science and spirituality.

One Health Calls for Bridges Between Worldviews

Annick de Witt is an educator investigating worldviews and the transformation of society. She stressed that today, political and cultural polarisation is driving people apart. It was part of the late postmodern age that there were no longer any meaningful narratives, and additionally fear and anxiety were being added to the mix. “We lurch from crisis to crisis and struggle to find the roots of the problems.” Therefore, de Witt stressed, we need to start looking at ourselves and how we look at the world. The climate and social crises point to a bigger crisis, the crisis of consciousness, of the spirit, because they indicate who we are and who we want to be. It is a crisis of ourselves. Today, everyone has their own worldview and thus their own image of reality. This has made it increasingly difficult to talk to each other. ”We’re really living in different worlds now in a way that we’ve probably never experienced as a global civilization.” We need to learn more about how we can engage, she urged, and how we perceive the world.

She recalled the philosopher Edgar Morin, who speaks of a polycrisis – that is, of interconnected crises. Everyone today is thrust into this existential exploration. According to de Witt, this exploration involves becoming clear about our unconsciously constructed worldviews, which create the overarching systems of meaning and significance regarding how we humans interpret, act, and co-create reality. What is reality? How did this world come to be like this? Whom or what can we trust? Who are the authorities in our system knowledge? What is a good person? These are the big questions of a worldview. Worldviews are mostly unconscious and yet provide meaning and significance, without which human life is hardly possible. “It’s like we’re wearing glasses without realizing it!”

De Witt quoted Dr. Richard Tarnas, the cultural historian: “Worldviews create worlds.” Neurobiology shows that it doesn’t make much difference to the brain whether something is really happening or whether we are just vividly imagining it. This, de Witt said, tells us something about the power of the mind and the imagination. The iceberg model is important here. It says that if you want to change a system as a whole, you have to go into the invisible depths, beyond behavioral patterns. This brings our worldviews and the dialogue between them into view. In her doctoral thesis, de Witt developed questions to bring unconscious worldviews to light. The awareness of our own view of the world makes us capable of talking.

Older people grew up with a traditional worldview, in which a hierarchy orders the world. This was followed by the modern worldview, in which technology and progress became the measure. The postmodern worldview places the individual at the top and negates the objective concept of reality; it is here that society fragments. As a fourth worldview, she named the integral spiritual worldview, in which we look for a new unity and interconnectedness, building the bridge between subject and object. Education, therefore, means understanding our own and also other worldviews in order to be able to engage in exchange with people of other worldviews, to “find a global space for solutions.” Her description that it is extraordinarily difficult to change one’s own worldview was thought-provoking. Having the contribution by de Witt at the beginning certainly helped the dramatic composition of the conference. The spiritual perspective, when it comes to the one great health, was present from the beginning.

‘One Health’ Calls for a Balanced Diet and Exercise

Christian Peifer, University of Mainz, chemist and pharmacist described the effect of substances that are far removed from nature. For example, Teflon, which is used to treat pans and clothes, does not occur in nature. Its carbon-fluorine bonds are the most stable bonds in organic chemistry, but there is no enzyme that has evolved in the course of evolution that can break this bond. They are forever chemicals. Today, there is not a square meter on earth that does not contain such manufactured chemicals. While in the 1980s, active pharmaceutical ingredients were mainly produced in Europe or the USA, today, production is concentrated in regions in India and China. The wastewater from these production sites causes the antibiotic ciprofloxacin to accumulate in some rivers at higher levels than is found in our own blood when taken as a medicine. Peifer reminded everyone that such concentrations produce resistant bacteria, which do not only stay in India.

The pandemic showed how quickly a virus or bacterium can spread globally. Peifer said he was concerned that, of 8,000 tonnes of environmentally impactful medicines in Germany, fifty percent were accounted for by just five active ingredients, metformin, ibuprofen, metamizole, aspirin, and paracetamol – all diabetes medicines and painkillers. Many patients tip half-full containers of antibiotic liquids down the drain so that they can put the glass into the recycling – good intentions with fatal consequences. Improper disposal accounts for about twenty to forty percent of the input into the environment. Many countries do not have efficient wastewater treatment plants, so active substances end up in the water. Peifer described how the drugs are developed in such a way that they are only broken down slowly in the body so that it is not necessary to take one tablet every hour but only one tablet a day. Enzymes similar to those in humans are found in nature so these substances then also persist for a long time outside the human organism. If a compound can be made to resist human enzymes, there is a good chance that it will also be enduring in the broader world, at least as far as bacterial breakdown is concerned.

Medicinal chemistry tracks down the so-called metabolization sites in the molecule and uses chemical groups that prevent an enzyme from causing oxidation. As a solution, Peifer suggests developing holistic approaches. “We need to do more prevention in the health system because if the problem doesn’t occur, you don’t need so much treatment and you don’t need to worry about all these active ingredients flushed down the drain. Most of the problems we have today, even in older people, could be effectively influenced by a balanced diet and a reasonable amount of exercise.”

More than ten percent of Germans suffer from diabetes, that is, almost ten million people. Many of them are treated with metformin. It is a synthetic compound that is not known to occur in nature, and there is not a single enzyme that can break it down. Less sugar would not only free millions of people from diabetes – it would solve this environmental problem. Moreover, according to Peifer, ninety-five percent of painkillers can be replaced by natural substances.

‘One Health’ Calls for Collaboration

Jakob Zinstag, veterinarian at the Basel Tropical Institute, has been involved with the One Health theory for 30 years. The institute runs 250 research projects in 133 countries. Zinstag was inspired by Calvin Schwab, a veterinary epidemiologist at the American University in Beirut, Lebanon. He worked with Dinka herders in Sudan and saw how closely people and animals live together there, as well as the importance of their healers. He called for not making a distinction in the paradigm between human and veterinary medicine.

“In the basic sciences of physiology, anatomy, pathology, and the origin of disease, we have the same body.” This became the starting point for Zinstag when he was asked to set up a research group at the Swiss Tropical and Public Health Institute in 1998 to improve healthcare for nomadic herders in Chad. In 2005, he wrote the first study to appear in the biomedical literature using the term ‘One Health’. The idea, however, was older; Rudolf Virchow had already said in connection with bovine tuberculosis that there was no difference between human and veterinary medicine.

Zinstag emphasized that health research required a deep systemic understanding of how humans, animals, and the environment interact. “So we need a deep ecological understanding of health.” When veterinarians and doctors work together, there are environmental, economic, and medical benefits. Besides this interdisciplinarity, the second pillar of ‘One Health’ is transdisciplinary. Zinstag described how in Chad the first task was to listen. “We need to connect science and society. In this way, non-academic actors and knowledge are included in the research process. These natural healers have no formal training, but they are environmental experts!” We Europeans, says Zinstag, would barely survive more than two weeks in the Central African desert. The population there has survived for centuries. The purpose of transdisciplinarity is to bring academic and practical knowledge together to create transformational knowledge. “So we are bringing decision-makers, the affected population, and the scientists under one tent.” There were many pitfalls in this. Zinstag describes such a meeting under the tent: How do you know who is the most powerful person? How do you avoid being politically instrumentalized? You have to be careful to be considered an honest broker. Zinstag: “If we manage to break the ice of mistrust and create an atmosphere of mutual understanding, then we can find solutions!”

Zinstag gives an example: a Tamashek woman said: “We know that Western medicine works, the vaccines and the medicines, but we hesitate to use them because they don’t have the barakah. Barakah in Arabic means ‘the blessing of God.’ So we ask how we can ensure that modern medicine is also seen as blessed by Muslim communities. And right there, the concepts of spiritual health and physical health go hand in hand. These are unexpected results that you get when you enter into a deep dialogue.

Zinstag asks, “So what, then, are the philosophical consequences?” We have to move from anthropocentrism to a multi-species ontology. It is about humans and about animals and about our microbiome. It was not possible to provide healthcare for Tuareg or Mayan communities without taking local epistemologies into account. In addition, as a third pillar of ‘One Health,’ a multi-epistemic perspective was needed that took the local context into account. From Cartesian determinism to process thinking. Zinstag mentions that the philosopher Alfred Whitehead, who thought about process theory and process theology, was born in the same year as Rudolf Steiner. But there was probably never any connection between Steiner and Whitehead. And I was actually brought by my wife, who is a Protestant pastor, to process philosophy via process theology.

‘One Health’ Calls for Understanding Life in its Aliveness

Bernd Rosslenbroich, University of Witten-Herdecke, also emphasized that life must be understood as a living process. As clearly as it was possible to distinguish a dead stone from a living animal, it was difficult to grasp scientifically what life was. Although we knew so much about the organism, about the cell, we could not grasp what life is. For centuries this question has preoccupied the life sciences. In addition to the mechanistic and vitalistic concepts of the organism, the third way of thinking, which can be described as organismic biology or the organismic organism, is little known. It originated at the beginning of the twentieth century.

Rosslenbroich mentioned Karl Voos, a leading microbiologist in the USA, who demands that we should stop thinking of the organism as a molecular machine, and Denis Noble, a renowned physiologist at Oxford University, who pleads for a new understanding of life in his book, The Music of Life.

Rosslenbroich thereby built a bridge to the anthroposophical concept of the etheric in its imprint on the material. To this end, he advocated a concept of life that cannot be reduced. The infinite diversity, complexity, and incomprehensibility of the living became clear when he developed sixteen characteristics of life and wrote them on the blackboard. Life is a network where cause and effect exchange with one another and are mutually dependent. The old understanding of genetics, that information only flows in one direction, from DNA to protein to trait, no longer applies. Feedback processes have long been known. “The organism seems to be very active in dealing with its DNA.”

We have to learn, says the biologist, that a cell integrates its components, is part of a whole and at the same time forms a whole. The components are part of the system and they create the whole, and at the same time the whole, the system, integrates the parts. With each successive description, the contradictory nature of life became clearer. Life means both autonomy from the environment and exchange with it.

This provided an arc on the first day of the three-day conference. Annick de Witt called for a conversation of worldviews to move from the standpoint to flux, and Bernd Rosslenbroich described this as a basic trait of life.

Translation Christian von Arnim

The contributions to the conference are available in English on Goetheanum.tv. This report only covers the first day of the three-day event.

Cover image Bernd Rosslenbroich, University Witten Herdecke, Annick de Witt, University Utrecht, Christian Peifer, University Mainz. All photos: Wolfgang Held