The demon Lilith has wandered the Earth and featured in the mythical imaginings of writers, artists, and poets for more than four thousand years. Something menacing surrounds this contradictory figure. Her significance has changed over the course of history. What does she signify today?

We encounter her in Sumerian records and in both Babylonian and Mesopotamian mythology. Later, she appears in Jewish sources as Adam’s first wife, before she is increasingly portrayed as a winged and seductive demon and succubus. In recent times, feminists have embraced her as a representative of independence and sexual liberation.1

“For the Sheer Pleasure”

The first time I encountered Lilith was when I read the Polish-Jewish author Isaac Bashevis Singer (1902–1991, Nobel Prize for Literature 1978). In the book Love and Exile, which he calls a “spiritual autobiography,” he describes a daily life steeped in Jewish folklore, where demons, ghosts, and other shadow creatures lurk in nooks and crannies—among them the demon Lilith.

As a young man in Warsaw’s intellectual circles, Isaac begins a relationship with Gina, who is twenty years his senior. Through her, he comes into contact with an erotic, primal world characterized by darkness, chaos, and desire. Isaac is plagued by guilt and hears inner voices from his orthodox family blaming him for having desecrated his soul, because through Gina, he has mated with the demon queen Lilith herself. Gina is red-haired, as Lilith is also depicted, and she in no way fits into the orthodox ideal of a passive, submissive woman. Gina and Isaac are swept up in a storm of boundless desire; they fall asleep but wake up again “in exactly the same fraction of a second, and we threw ourselves at each other with a hunger that astonished us.”2

The short story “A Gentleman from Cracow” revolves around the inhabitants of the town of Frampol who, in their great distress and poverty, are visited by the demon Ketev Mriri, disguised as a wealthy doctor. By showering the people with bread and money, the wealthy doctor from Krakow immediately becomes a prime candidate for the town’s promiscuous women. Eventually, they all gain free access to elegant clothes so they can dress up for a lavish ball where the gentleman will choose his bride.

The one he ultimately chooses is none other than Lilith, disguised as the seventeen-year-old Hodle, known as the town whore: she was “tall and lean, with red hair and green eyes [. . .]. She had the shrewdness of a bastard, the quick tongue of an adder [. . .]. [H]er face was freckled, and her hair disheveled.”3 Her future husband asks her if she has slept with Jews or Gentiles, to which she replies, “With both.” When asked if she did it to earn money, she answered: “No, for the sheer pleasure.” She does not regret what she has done and does not fear the torments of hell: “I fear nothing—not even God. There is no God.”4 “And then the gentleman from Cracow revealed his true identity. [. . .] [A] creature covered with scales, with an eye in his chest, and on his forehead a horn that rotated at great speed. His arms were covered with hair, thorns, and elflocks, and his tail was a mass of live serpents.” Now, “Hodle’s dress fell from her, and she stood naked. Her breasts hung down to her navel, and her feet were webbed. Her hair was a wilderness of worms and caterpillars. [. . .] Then it was understood that Hodle was really Lilith, and that the host of the netherworld had come to Frampol because of her.”5 The black magic that the demon couple Ketev Mriri and Lilith unleashed on the inhabitants also set the city’s buildings on fire. When dawn broke and the sun rose “crimson with shame,” Frampol lay in ashes. Worst of all were the infants: their “cribs were burned, their little bones were charred. [. . .] The wailing and crying [of the mothers] lasted long.”6

Magical Source of Power and Anti-Mary

In Singer’s work, we encounter two essential characteristics of the Lilith figure. The first is that the driving force behind sexuality is detached from norms, precepts, and traditional forms of coexistence. Here, it is all about pleasure and ecstasy. The orgy described by Singer may evoke associations with the Babylonian-Assyrian Ishtar mysteries. Ishtar, the goddess of sensual love, definitely has some “Lilith-like” traits. In the Ishtar rituals, she was served by eunuchs and a procession of men and boys who dressed as women and gave themselves over to women’s activities. According to Assyriologist Archibald Sayce, the temples of Ishtar “were filled with the victims of sexual passion and religious frenzy, and her festivals were scenes of consecrated orgies.”7 Like Lilith, Ishtar could also have love affairs with mortal men, but for the most part, she brought ruin and death to her lovers.

The second characteristic of Singer’s portrayal of Lilith is the danger she poses to pregnant women and infants. Lilith, as a child murderer, is a complex and complicated theme. Certain Christian circles, especially in the US, associate her with women’s right to abortion. There is even an aid organization in the US called the Lilith Fund, which provides financial and emotional support to women living in states where abortion is prohibited.8 Catholic theologian Scott Smith writes that Lilith is a parallel to the Antichrist, namely Anti-Mary. According to tradition, Lilith is a sexually lustful demon who comes at night and steals newborn babies; she is, according to Smith, “the tailor-made patroness of the abortion movement.”9

In the feminist journal Lilith, Jewish psychologist and feminist Evelyn Torton Beck writes that Singer showed sympathy for the feminist project when he claimed that “Judaism had made a historical mistake by not teaching women the Torah [. . .].”10 Singer also believed that Jewish women should have full religious rights in the synagogue, including the right to ordination. At the same time, Beck criticizes the parts of Singer’s work that she sees as chauvinistic stereotypes, as when he portrays women as sirens and temptresses, demons and witches. In doing so, Beck argues, Singer repeats a “male-centered” positioning of women as “the other.”11

There is something in Singer’s portrayal of female demons that contrasts with that of male demons: the latter’s evil comes from sources outside themselves, while the evil of female demons seems to point to something corrupt in the woman’s own soul. Can a more flexible concept of gender overcome this interpretative dichotomy? Can both male and female beings and demons be interpreted as different aspects of human beings as such, regardless of gender? In my own exploration of the figure of Lilith, I see that human beings can experience Lilith as an inner mental entity.

From Adam’s Partner to Deadly Seducer

The perception of Lilith as a succubus who seduces men already appears in Sumerian texts. Ethnographer and orientalist Raphael Patai writes that the Babylonian Lilith visited men at night and bore them ghost children. One gets the impression of a sterile sexuality where the result never ends in a sensual child but rather in a supernatural demon child. According to historian Vanessa Rousseau, Lilith devours men’s sperm until they are completely exhausted, and she also abducts and devours children, which Rousseau interprets as her “suffocating all reproductive creatures until they are sterile.” Lilith thus drives men to “unproductive use” of their energy.12 The Sumerian Lilith is further portrayed as “a beautiful maiden,” but also both a “harlot and a vampire, who once she chose a lover, would never let him go, but without ever giving him real satisfaction.”13

In Jewish mysticism, according to Jungian psychologist Barbara Black Koltuv, she was portrayed as a demon queen who mated with the evil angel Samael. Lilith-Samael emanated from beneath the throne of glory and was a distinctly androgynous being with two faces that later separated. Samael was also equated with Satan as a high-ranking and leading demon. In the Kabbalistic text, the Zohar, “the female of Samael [i.e., Lilith] is called a ‘serpent,’ ‘a wife of harlotry,’ ‘The End of all Flesh’ [. . .], and the end of days.”14 According to Rousseau, Lilith represents an ambiguous sexuality, and one sees a clear “androgynous nature of this primordial woman.”15

In Jewish commentaries, Koltuv writes, the first human being, as described in Genesis, is also an androgynous creation with two faces turned away from each other. Only later did God divide Adam in two and create a back for each of the faces. Lilith is therefore the first Eve, the female Adam, also called Adamah.16 In the Zohar, it is written that there is a fiery female spirit in the depths of the great abyss named Lilith, who was the first to cohabit with man. In the earliest material on Lilith’s biography, the Alphabet of Sirach [c. 700–1000], it is stated that she considered herself equal to Adam. Since she too was born of the earth, she demanded the same sexual rights as him; she wanted to be active and refused to settle for a lying position during intercourse. But Adam disagreed. They could not find peace with each other, and Lilith broke with Adam and at the same time broke the taboo: she spoke God’s name, which was not to be uttered, and later became a night demon, a winged creature with long flowing hair who sought out sleeping women and men. She became morally dangerous, first and foremost, for men who slept alone but also for women. According to Koltuv, she could plant hot, erotic dreams that caused nocturnal orgasms for anyone who slept alone, regardless of gender.17

Through her break with Adam and God, Lilith was increasingly portrayed as a threat to pregnant women and infants, indeed to the family structure as a whole. “Thus, the daughters of Eve,” writes Koltuv, “suffer the two aspects of the feminine: [. . .] Eve is the life-nourishing side of the instinctual feminine, while Lilith is its death-dealing opposite.”18 The stories about Lilith as a child murderer are also full of contradictions. She is both the Lilith who plays with infants while they sleep and makes them dream and smile—but she also causes the hair on the back of their heads to become tangled when she plays with them, tickles them, and makes them roll around in laughter and delight. But, Koltuv mentions, the same Lilith also causes epilepsy, suffocation, and death.19

The Nordic Lilith

In Nordic folklore and tradition, Lilith is associated with Lucia or Lussi (Latin, “light-bearing”). Here, Lucia is not the Catholic saint but a dark, demonic figure. According to ethnologist Målfrid Snørteland, “the old Lussi was [. . .] the complete opposite of the Lucia celebrated by kindergartens and schools today. [. . .] Professor of folklore Olav Bø has pointed out that Lucia has the same etymological origin as Lucifer. Lussi is said to have been Adam’s first wife and was considered the ancestress of the underground people.”20 In Värmland, Lucia was portrayed as both a whore and a ghost, and in Västergötland as a child murderer. In Askvoll, too, the underground people are her descendents.21 Lucia has also “taken on traits from the dark and demonic underworld of popular belief.”22 Lussi Night (Lussinatta), which has also been called the Lussi Journey (Lussiferda) and Lucifer Night (Lucifernatta), has clear similarities with the pagan Norse’s Wild Hunt of Odin (Åsgårdsreien, “Ride of Asgard”), where an army of demonic dark forces ravaged the land.

In 1908, folklorist Levi Johansson refers to a farmer who believed that Lucia was actually called Lilith and was Adam’s first wife. Here, too, she is described as red-haired, brown-eyed, and evil. “He had heard this in his childhood from an old woman who went around the parish carding wool.”23 Anthropologist Katarina Ek-Nilsson points out that “Lucia was a light-shy and, according to many records, dangerous creature. She could take the form of a bird of prey that wanted to eat children.”24 The Norse Lucia/Lussi also has a male counterpart. In Swedish and Norwegian folklore, the connection between Lussi and Lucifer is obvious.

Ancestors of the Hulder People

In Hardanger (Norway), Lussi had characteristics of a hulder [a seductive forest creature] and a female Lucifer (Lussifær). “In front, she was beautifully adorned like a Hardanger bride, with a silver crown on her head, silver jewelry, and silver chains on her chest, a silver belt around her waist, and a red skirt or dress. But behind, Lussifær was hideous and repulsive, resembling a half-rotten linden tree.”25 The Nordic Lilith was, therefore, also perceived as an archetype for the Nordic huldra, and in popular belief it was said that the ancestress of the huldras was “Adam’s first wife, Lussi [. . .]” and that the huldra or hulder were descendants of fallen angels.26

Social anthropologist Marit Myrvoll, who researched the beliefs of the coastal Sámi people, describes the huldra “as a seductress and temptress for the men of the village” who, when they took a break from work, “could dream of how the huldra came and made sexual advances [. . .].” In Sámi folklore, too, we encounter the biblical story of creation as the origin of what later became the huldra people.27 Vigdis Ellingsen describes them as “cunning, sophisticated, sensual, and alluring.” It is also said of the subterranean beings (the hulder) that they were “Lucifer’s angels who rained down from heaven for three days.”28 The hulder could also be dangerous to women and infants: “Humans were particularly vulnerable to the hulder during transitional phases. Women who had just given birth and had not yet had time to baptize their child [. . .] were particularly vulnerable.”29

In Norwegian folklore, too, we also find stories about how to protect infants from the hulder. It was considered a good remedy to place the Bible under the pillow of an unbaptized child, a tradition that is said to have continued into our time.30 The Nordic Lussi-Lussifær also has features of the duality we saw in Lilith: something beautiful and attractive “in front,” that is, in the immediately visible, but “behind,” more hidden, corrupt, decaying, deadly.

Lilith is a complex and powerful figure. In Babylonian-Sumerian and Jewish sources, we discover layer upon layer of beauty and ugliness, fiery striving for freedom and destructive seduction, family breakdown and sterile sexuality. Etymologically, we also find an interesting contrast between darkness and light. Lucia/Lussi means luminous, and she was also called Lucifæra, a feminization of the male name Lucifer (Latin, “light bearer”). At the same time, Lilith is etymologically related to the Hebrew female name Layil and the Arabic Laila, both of which mean “night.” Dark and ugly are attributes associated with Lussi and Lucia, but at the same time, she was the ancestor of the hulder, who are portrayed as both beautiful and bright. In the Qabbalot, Lilith is also portrayed not only as fearsome but also as beautiful: “Lilith has the body of a beautiful woman from her head to her navel, but from her navel down she is flaming fire.”31 Lilith’s character is fundamentally contradictory; she is beautiful but ugly and dangerous; her name and character are at once dark and luminous.

Lilith and Lucifer

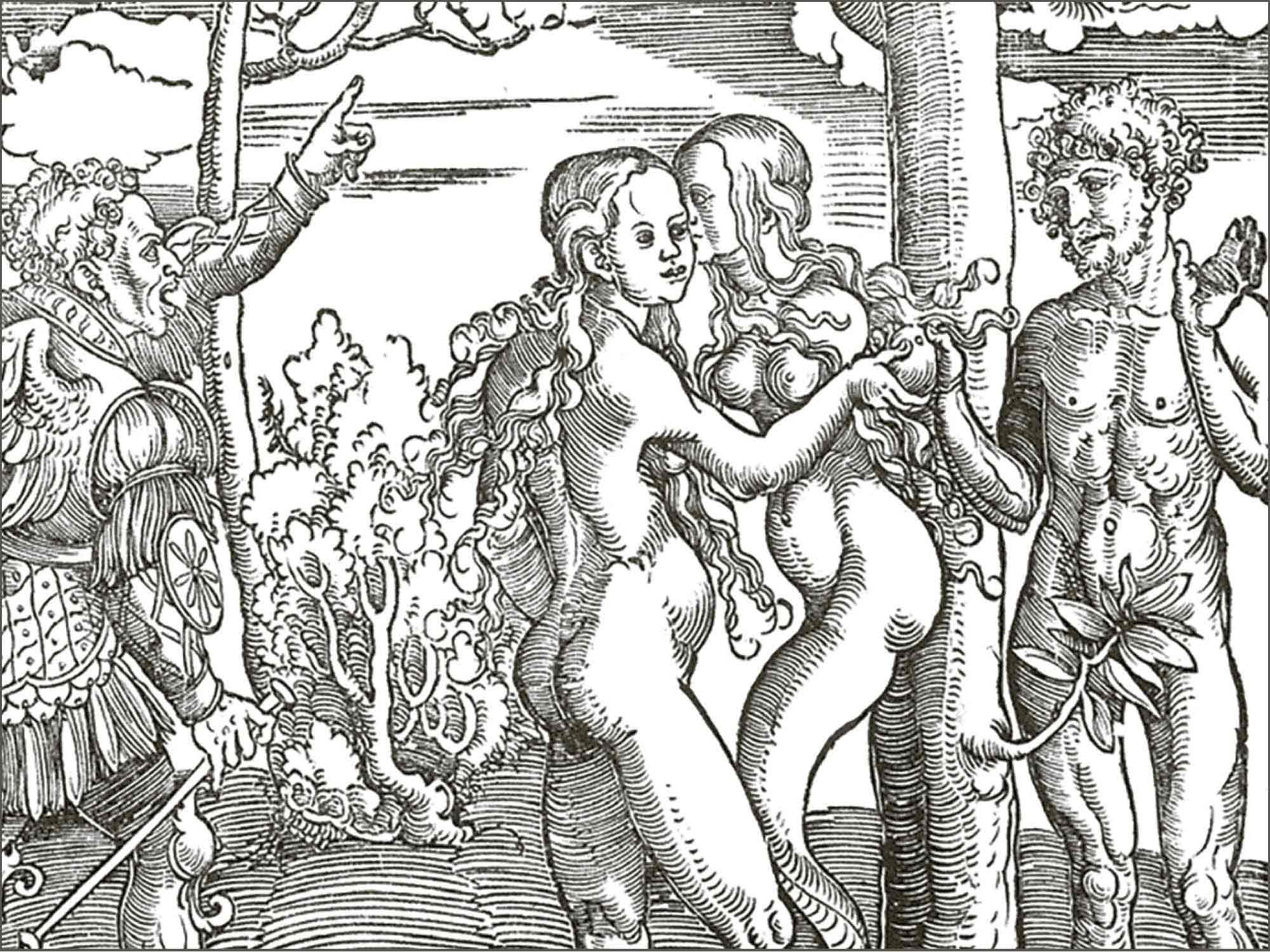

According to Kabbalistic writings, Lilith was the last to leave the Garden of Eden after the expulsion, and the reason for this is that she played a decisive role in bringing it all about. She transformed herself into the very serpent that lures and tempts Adam and Eve to eat from the tree of knowledge. In medieval consciousness, Lilith and Eve were closely linked as representatives of sinfulness. In a woodcut from 1470 [cf. image], Lilith is depicted with a crown, wings, and a serpent’s tail under the tree of knowledge, where she offers the forbidden fruit to Eve. The fact that the serpent Lucifer is portrayed as both male and female suggests that it has been perceived as an androgynous being. Within sections of the Christian anti-trans movement, Lucifer is portrayed as an occult transsexual entity: “Lucifer is indeed the ‘god’ of the modern transgender movement,” according to a Bible study site.32

Julian Strube examined the demon Baphomet, which some have interpreted as a version of Lucifer/Satan. This demon is characterized by a goat’s head, wings, and female breasts, i.e., an androgynous form.33 In occultism, Lucifer is not described as exclusively evil and dark. An interesting contribution in this regard comes from the founder of theosophy, Helena Petrovna Blavatsky. For her, it was self-evident—already in the 1870s—that women had the same rights as men, and many of the female members of the Theosophical Society were also associated with the early modern feminist movement. Blavatsky claimed that Lucifer brought autonomy and divine wisdom to humanity and is “the spirit of intellectual enlightenment and freedom of thought.”34 This sympathy also had political and feminist implications. According to Per Faxneld, theosophy emerged as a “protest movement and counterculture culture, and [has] links with socialism and feminism.”35

Lilith-Lucifer thus becomes the symbol of both the active, sovereign woman who refuses to be merely a product of man’s rib and the Luciferian seduction that tempts humans with freedom and independence. Lilith is sometimes portrayed as Lucifer’s sister, which I interpret as a metaphor for Lucifer’s androgyny. In the early twentieth century, the poet George Sylvester Viereck wrote: Like Lucifer, Lilith is a rebel. She is not attracted by morality but by an indomitable intellectual curiosity. She transcends sex, even in its sexual perversions. Lucifer recognizes her as his kin; by this sign, she honors him as her brother.36 Viereck describes Lucifer and Lilith as inner dimensions of human beings themselves. Such anthropomorphism of external religious/spiritual figures into internal mental figures, as seen in Viereck through poetry and Koltuv through psychology, is clearly evident in feminism’s use of the Lilith figure as well.

Feminist Icon

According to Koltuv, “The war between Eve and Lilith rages on [. . .]. Eve can have her needs met in a relationship. Lilith cannot. She must cut and run. She refuses dependency and submission. She will not be bound or pinned down. She needs to be free, to move, and to change.” Thus, she becomes “an aspect of the individuating feminine ego that can only develop in the wilderness, unrelated, without eros and childless, ever jealous of Eve, who remains in man’s embrace.”37

Judith Plaskow treats the Lilith/Eve dichotomy somewhat differently. Here, the separation ends in a productive reconciliation. In a short story, she rewrites the story of Lilith, Adam, and Eve as a metaphor for recent feminist thinking. In Plaskow’s short story, “Lilith is banished by God, at Adam’s request, for not being the subservient woman, thus epitomizing the birth of feminist thinking.”38 Eve, on the other hand, the submissive, good wife, appears as a symbol of women who are still unaware of their rights. Lilith tries to return to the Garden of Eden. But Adam and Eve have built strong, high walls. Eve is told stories about how evil and dangerous Lilith is. One day, Eve catches sight of Lilith on the other side of the wall and is deeply astounded to see only a woman like herself, not the enormous monster that has been ingrained in her consciousness through the stories she was told. Eve and Lilith meet, and an empathetic sisterhood arises between them.

Meanwhile, the relationship between God and Adam is turning sour, as their roles as creator and creature become blurred and distorted. They become frightened and divided when Eve and Lilith return to the garden, “[. . .] bursting with possibilities, ready to rebuild it together.”39 Plaskow emphasizes how destroying women’s communities and turning women against one another is an essential way of maintaining patriarchal power. The end of the short story is “a utopian hope for the future of society but is also symbolic of the kind of experience women should have if they embrace the ‘sisterhood’ of feminism.” The union of Lilith and Eve resolves the contradiction between the angry, liberated, autonomous woman and the gentle, marital, maternal woman. “Instead of being a reactionary monster,” Plaskow hereby presents Lilith “as a suppressed woman that managed to vindicate her freedom, becoming an admirable paradigm for all women in the world struggling with women’s oppression.”40

“Men experience [Lilith] as the seductive witch, the death-dealing succubus, and the strangling mother. For women, she is the dark Shadow of the Self that is married to the devil. It is through knowing Lilith and her consort that one becomes conscious of one’s Self.”41 Lilith represents a strong and independent, at times chaotic, Eros. Her problem is that she cannot commit to a long-term relationship. Unlike Eve, she does not find peace in lasting marriage and family life but craves ever-new adventures and sexual seductions. Lilith is bound by her own restlessness, her desire to be desired. At the same time, in a feminist context, she appears as an independent, rebellious, and sexually liberated character. “Lilith is a myth that has evolved over time and been filtered through religious interpretations.”42

Is it possible to approach the force field represented by Lilith independently of biological sex? For me, the answer is yes. Plato once had Socrates talk about the mythical figure Typhon. If we replace Typhon with Lilith, his statement can be summarized as follows: “I look not into them but into my own self: Am I a beast more complicated and savage than [Lilith], or am I a tamer, simpler animal with a share in a divine and gentle nature?”43 The Lilith/Lussi force within us can embody repressed emotions and appear liberating, beautiful, and sovereign. If this sovereignty and beauty are also permeated by the urge to be desired, the force that should have a liberating effect can become an explosive, ecstatic rapture that tears people from their earthly roots, causing them to lose their connection to the familiar, the everyday, the committed, and the social. In the worst case, what should be liberating can trap people in a realm without norms, where lust and chaos reign, but gives no stable foundation upon which we can build individually and socially with one another for the long term.

Translation Joshua Kelberman

Footnotes

- Janet Howe Gaines, “Lilith: Seductress, Heroine, or Murderer?,” Bible Review 17, no. 5, (2001), quoted in Judit M. Blair, De-Demonising the Old Testament: An Investigation of Azazel, Lilith, Deber, Queteb, and Reshef in the Hebrew Bible (PhD, University of Edinburgh, 2008), 27.

- Isaac Bashevis Singer, Love and Exile (Oslo: The Norwegian Book Club, 1987), 123.

- Isaac Bashevis Singer, “The Gentleman from Cracow: A Story,” Commentary (September 1957).

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Archibald Sayce, Lectures on the Origin and Growth of Religion as Illustrated by the Religion of the Ancient Babylonians (Edinburgh: Williams and Norgate, 1891), 266.

- The Lilith Fund, Mission, Vision & Values, accessed February 6, 2026.

- Scott Smith, “The Anti-Mary: The Terrifying New Patroness of Abortion, Lilith,” The Scott Smith Blog (September 05, 2017).

- Evelyn Torton Beck, “I. B. Singer’s Misogyny,” Lilith (1979).

- Ibid.

- Vanessa Rousseau, “Lilith: Une androgynie oubliée” [Lilith: A forgotten androgyny] Archives de sciences sociales des religions 123 (July–September 2003): 61–75.

- Raphael Patai, The Hebrew Goddess (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1990), 222.

- Zohar (Sefer ha-Zohar), “Vayetze, Chapter 4,” 23.

- See footnote 12, p. 4.

- Barbara Black Koltuv, The Book of Lilith (York Beach, ME: Nicolas-Hays, Inc., 1986), 10.

- Ibid., 39.

- Ibid., 81.

- Ibid., 85.

- Målfrid Snørteland, “Førjulstid og juletradisjonar i eldre tid, del 1, del 2” [Pre-Christmas season and Christmas traditions in the olden days, part 1, part 2], Sjå Jæren (2003): 7–35; quotation, p. 14.

- Brynjulf Alver, “Lussi, Tomas og Tollak: Tre kalendariske julefigurar” [Lussi, Tomas, and Tollak: Three figures of the Christmas calendar], in Nordisk folktro, ed. Bengt af Klintberg, Reimund Kvideland, and Magne Velure (Stockholm: Nordiska museet, 1976), 105–126.

- Ørnulf Hodne, Jul i Norge: gamle og nye tradisjoner [Christmas in Norway: Old and new traditions] (Oslo: J.W. Cappelen Forlag, 1990), 34.

- Levi Johansson, quoted in Katarina Ek-Nilsson, “Lucia, Lussi och lussebrud: Lilits metamorfoser [Lucia, Lussi, and Lussebrud: Lilith’s Metamorphoses],” Nätverket 15 (2008): 56–62.

- Ibid., 58.

- See footnote 21, p. 113.

- Sveinung Lutro, “Hulder,” Store norske leksikon, last updated Nov. 26, 2024, accessed February 6, 2026.

- Marit Myrvoll, “Fortolkning og forklaring av forestillinger om hulder og draug [Interpretation and explanation of beliefs about hulder and draug],” Tradisjon: Tidsskrift for folkloristikk 30, no. 2 (2000): 27–36.

- Vigdis Ellingsen, De usynlige: om hulder og andre underjordsvesen [The invisible: On hulder and other underground creatures] (Brønnøysund: Brønnøysund bokhandel, 1994), 13.

- See footnote 26.

- Per Ottesen, Huldra: Sagn og tradisjoner om de underjordiske [Huldra: Legends and traditions about the underground creatures] (Oslo: Orion Forlag, 2005).

- Raphael Patai, Gates to the Old City: A Book of Jewish Legends (Northvale, NJ: Jason Aronson, 1988), 464, quoting from R. Yaʿaqov and R. Yitzḥaq, Qabbalot [Kabbalah], ed. Gershom Scholem, Maddaʿe ba-Yahadut (Jerusalem, 1927), 2:257.

- Steve Barwick, “Lucifer: The Divine Androgyne, Ancient God of the Modern Transgender Movement,” Have Ye Not Read? (Apr. 3, 2018), accessed February 6, 2026.

- Julian Strube, “The ‘Baphomet’ of Eliphas Lévi: Its Meaning and Historical Context,” Correspondences 4 (2016).

- Helena Petrovna Blavatsky, The Secret Doctrine, vol. 2 (Pasadena, CA: Theosophical University Press, 1888), 162.

- Per Faxneld, “Blavatsky the Satanist: Luciferianism in Theosophy, and its Feminist Implications,” Temenos 48, no. 2 (2012), 204.

- George Sylvester Viereck, “Queen Lilith,” in The Candle and the Flame (New York: Moffat, Yard and Company, 1912).

- See footnote 16, p. 83.

- Louise Tracey Smith, Lilith: A Mythological Study (PhD diss., University of Bedfordshire, 2008), 27. Judith Plaskow, “The Coming of Lilith: Toward a Feminist Theology,” in Womanspirit Rising: A Feminist Reader in Religion, ed. Judith Plaskow and Carol P. Christ (San Francisco: Harper & Row, 1979).

- Ibid.

- Pinelopi Diamantopoulou, How Scholars Use the Figure of Lilith within Jewish Feminism (Master’s thesis, University of Copenhagen, 2017), 33.

- See footnote 16, pp. 6–7.

- See footnote 38, Smith, 19.

- Plato, Phaedrus, trans. Alexander Nehamas and Paul Woodruff (Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing Company, 1995), 230a.