Geniuses and people needing support have one thing in common: the unconditionality with which they deal with conditions.

For some, the unconditional—the absolute—has such a powerful effect on the conditions of existence, that the conditional becomes transparent to the invisible that shapes and determines the visible. For others, the conditions of existence are so narrow and specific that they need support and accompaniment in order to maintain their existence at all, and—precisely, by way of this special arrangement—they bring forth the essential, not least in those who accompany them.

Over two hundred years ago, when Novalis called for the world and human beings to be romanticized, he saw this as the only way to find the unconditioned, instead of always just the thing. And every line collected among his various fragments mirrors his deep love for the development and education of what is purely human, the aim of which is a self-understanding that learns to understand others: “The highest task of development [Bildung] is to seize one’s transcendental Self, to simultaneously be the ‘I’ of one’s ‘I.’ All the less alienating is the lack of perfect feeling and understanding for others. Without a perfect self-understanding, one will never learn to truly understand others.”1

Then, not quite one year ago, when Victoria Öttl was invited to closely observe what emerged within her while writing out the verses of Steiner’s Soul Calendar, she made an ingenious discovery. On October 10, 2023, she wrote: “The ‘I’ is present in every verse. Even when the word ‘I’ is not in the verse, the ‘I’ is inwardly present everywhere. I was already struck by this in the last verses, so I thought to myself that I had to observe how it further develops throughout all the verses.”2

By the late eighteenth century in Europe, the world had become so alien to the ‘I’ that the ‘I’ was able to posit itself and designated everything else as non-‘I’ as the world (Fichte). In the early twenty-first century, the alienation between human beings and the world has become life-threatening. Today, we are increasingly witnessing a human-made death of nature, and we know that it urgently needs our understanding and, indeed, our loving support. This assistance certainly does not come from looking at numbers and figures but rather from romanticizing them. “The world must be romanticized. This yields again its original meaning. . . . By giving a higher sense to the ordinary, a mysterious semblance to the everyday, the dignity of the unknown to the known, and the appearance of the infinite to the finite—I romanticize it.”3

As an aesthetic method, all romanticization aims to transform the world; it begins with the individual human being in one’s own soul. With this in mind, Rudolf Steiner focused his attention in his first great verse epic4 entirely on the relationship between the human soul and nature, or more precisely, on the relationship between the soul’s rhythm of perception and thought, largely emancipated from space and time, and the natural events that take place entirely according to the rhythm of the seasons. Nature, herself, does not yet undergo any change as a result; however, the poeticized intuition and perception of nature enables the soul to recognize itself in the picture of the course of the year, not as a system or machine, but as a living, feeling being in its own right. This feeling awakens only gradually and initially appears—like all feeling self-knowledge—as a questioning that is increasingly aware of its ignorance.

Victoria Öttl depicts this awakening in her life and her work with the fifty-two verses at the threshold between summer and fall: “To be honest, I don’t exactly know how the soul-being should become aware of herself. Does this have anything to do with creating? Is it that the soul-being creates itself and becomes aware of itself in creation?”5

And a little later, shortly before the ingenious discovery that the ‘I’ is everywhere: “Does that mean me there, as a being? The soul belongs, in some way, to Being, I believe. I am the Being that observes itself, yes?”6

Steiner’s verse epic dedicated to the relationship between soul and nature is directed at a feeling self-knowledge and thereby evokes it, just as an ‘I’ first becomes an ‘I’ when it is addressed as a ‘Thou.’7 This feeling self-knowledge opens up access to an ‘I’ that does not want to dominate but gives meaning, cognizes affiliations, and, ultimately, perceives how everything is connected with everything, yielding again its “original meaning.” This perception is emergence and creation.

Feeling self-knowledge steps into the place of alienation between human beings and the world—especially where people in need of assistance, accompaniment, and works of genius come together.

Translation Joshua Kelberman

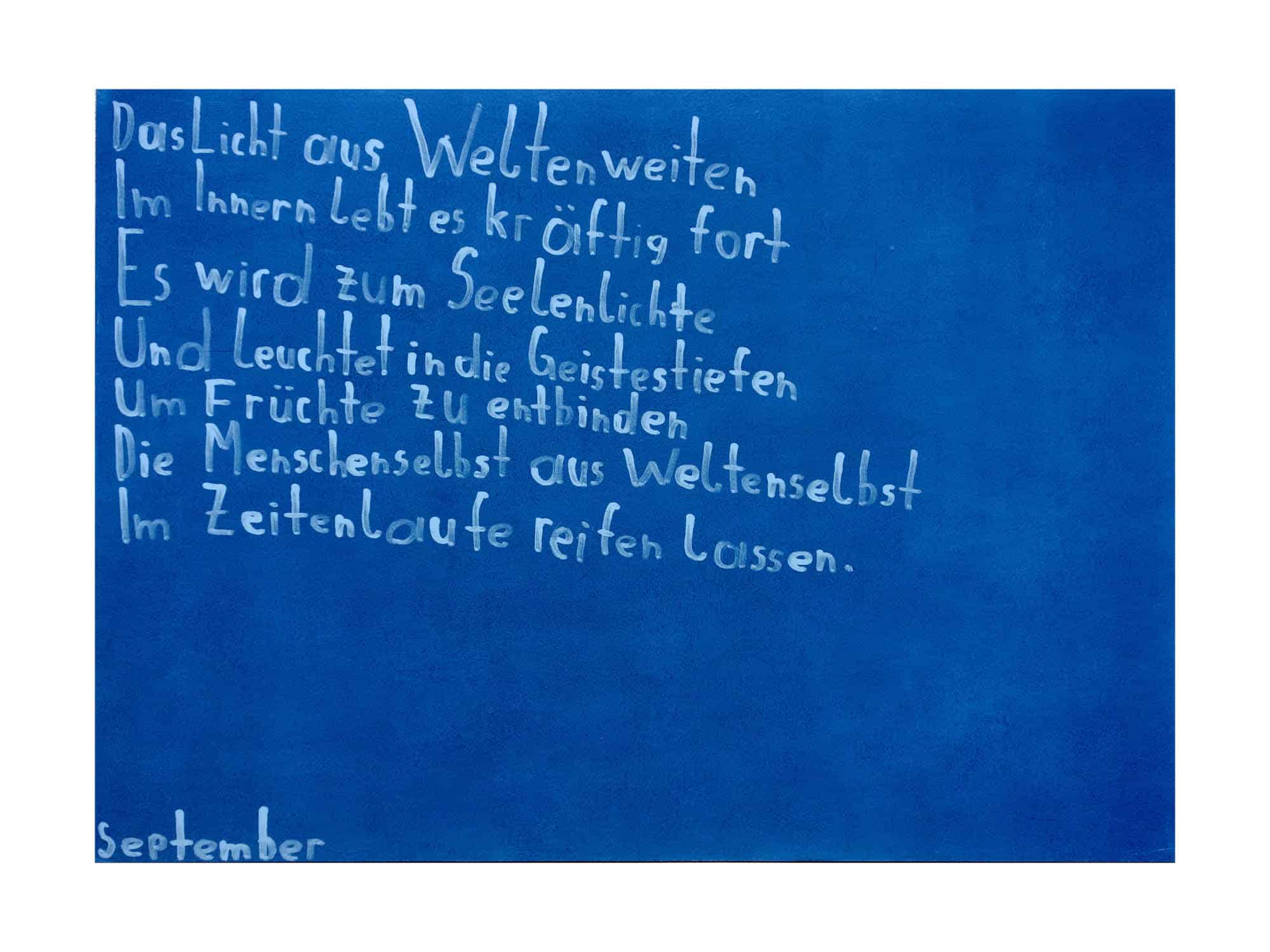

Image Panel #26, Victoria Öttl (writing), Hannes Weigert (concept/colour), acrylic on hardboard, 50 × 70 cm. The Painting Studio, 2021-22

Footnotes

- Novalis, Pollen, no. 28 in The Early Political Writings of the German Romantics, F. C. Beiser, ed., Cambridge Texts in the History of Political Thought (Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press, 1996), p. 14.

- Victoria Öttl and Hannes Weigert, Soul Calendar, Goetheanum, Dornach, Switzerland, Oct. 2–6, 2024, verse 28; see also “At the Painting Studio: The Soul Calendar Panels,” in the Goetheanum Weekly, Issue 35.

- Novalis, Mathematical Fragments (1798–1800), translated by David W. Wood, in Symphilosophie 3 (2021), p. 282.

- Steiner created two great verse epics: The first, in 1912/13, describes a loving, understanding relationship between soul and nature in the Soul Calendar: Rudolf Steiner, Calendar 1912/13 (Great Barrington, MA: SteinerBooks, 2003); the second, in 1924, tells of this relationship between ‘I’ and spirit: Rudolf Steiner, Esoteric Lessons for the First Class of the School of Spiritual Science at the Goetheanum, CW 270, 4 vols. (Dornach: Rudolf Steiner Press, 2020).

- See footnote 2, verse 24.

- See footnote 2, verse 27.

- Emmanuel Levinas, Entre nous: Thinking-of-the-Other (New York: Continuum, 2006.)