Historical Studies and Historical Reality.

“Eco-products for Nazis” was the headline of an article in the September 5, 2025, issue of the news magazine Der Spiegel.1 The subtitle read: “In the Dachau concentration camp, the SS experimented with anthroposophical methods and remedies using forced labor. The natural cosmetics company Weleda also played a role.” Included in the article were photographs of Rudolf Steiner, Margarete Himmler (the wife of the SS chief), Sigmund Rascher and another SS doctor conducting human experiments on concentration camp prisoners in Dachau, prisoners performing forced labor, buildings belonging to the Dachau SS operation of the German Research Institute for Nutrition and Food (DVA, Deutschen Versuchsanstalt für Ernährung und Verpflegung), along with images of the Weleda logo—and a photo of historian Anne Sudrow. The report served as an effective promotion for her book Heil Kräuter Kulturen. Die SS, die ökologische Landwirtschaft und die Naturheilkunde im KZ Dachau [Healing herb cultures: The SS, organic farming, and naturopathy in the Dachau concentration camp]. The book was published a few weeks later by Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht in Göttingen and made available to the news magazine in advance.2

A “Network of Anthroposophists in the SS”?

In his article, Spiegel author Stefan Hunglingern quotes from the monograph but also walks with the historian across the grounds of the former DVA facility. He emphasizes that there was an active “network of anthroposophists” within the SS, consisting of biodynamic farmers, gardeners, and an SS doctor (Sigmund Rascher), who were not victims but perpetrators in the context of the Dachau concentration camp and pursued their own interests. According to Hunglingern, based on the supposed research of the “clairvoyant” Steiner, profitable anthroposophical enterprises had already emerged in the 1920s (including the pharmaceutical manufacturer Weleda). Biodynamic agriculture, in particular, then received special support from the SS during the time of National Socialism, specifically as an instrument for cultivating the new “living space” [Lebensraumes] after the conquests in Eastern Europe in the course of World War II.

At the SS’s DVA facility in Dachau, Weleda’s former head gardener, Franz Lippert, and another Weleda gardener, Erich Werner, conducted botanical studies on the huge area cultivated by prisoners. SS doctor Rascher, who carried out cruel human experiments (high-altitude/low-pressure and freezing) in experimental block 5 of the concentration camp, was also associated with Weleda. Reportedly, the anthroposophical “network” within the SS at that time has been deliberately “concealed” to this day. According to Hunglingern and Sudrow, consumers of Demeter or Weleda products should be conscious of the inhumane support their manufacturers received not so long ago and the collaboration with the Nazi and SS regime that underlies these morally tainted products. According to the implicit statement in Der Spiegel, anyone who buys Demeter or Weleda products becomes a belated beneficiary of the Nazi concentration camps and the labor, blood, and ashes of innocent people.

Not Dealt With and Obscured?

With few exceptions, the article describes facts that have been known for decades from historical studies and publications—albeit with deliberate exaggeration and biased interpretation. The delivery of Weleda frostbite cream to Sigmund Rascher in January 1943 was made public by Götz Aly in early 1983. From 1991 to 1993, Arfst Wagner published five volumes of “Documents and Letters on the History of the Anthroposophical Movement and Society during the Time of National Socialism” [Dokumente und Briefe zur Geschichte der Anthroposophischen Bewegung und Gesellschaft in der Zeit des Nationalsozialismus] from state and private archives (Volume III: “Biodynamic Farming. Materials on Sigmund Rascher” [Biologisch-dynamische Wirtschaftsweise. Materialien über Sigmund Rascher]). In 1999, Uwe Werner took into account all the material available to him at that time on the relationship between the Reich Association for Biodynamic Agriculture and Horticulture [Reichsverband für biologisch-dynamische Landwirtschaft und Gartenbau] and the SS and the DVA, as well as on Franz Lippert and Sigmund Rascher, in his comprehensive monograph Anthroposophists in the Time of National Socialism [Anthroposophen in der Zeit des Nationalsozialismus].

Numerous other publications on Lippert and the DVA followed, including the work of Jens Ebert, Tanja Kinzel, Meggi Pieschel, and Kristin Witte in 2021. In the spring and early summer of 2024 and in the early summer of 2025 (two months before Sudrow’s monograph), three comprehensive volumes on the biodynamic movement during the time of National Socialism, as well as on anthroposophical doctors and anthroposophical drug manufacturers (1933–1945), were finally published—the result of several years of research projects and with the participation of scientific advisory boards with no connection to anthroposophy.3 The documentary material, insofar as it concerned persons or institutions close to anthroposophy, had thereby already been carefully and critically examined before Anne Sudrow’s work, and had not been deliberately “obscured.”

Merits and Shortcomings of a Publicly Funded Study

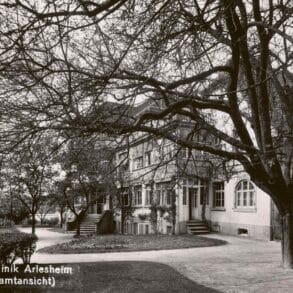

Of lasting value in Sudrow’s book publication—which bears the logos of the Dachau Concentration Camp Memorial Site [KZ-Gedenkstätte Dachau], the Federal Government Commissioner for Culture and the Media [Beauftragten der Bundesregierung für Kultur und Medien], and the Bavarian State Ministry of Education and Culture [Bayrischen Staatsministeriums für Unterricht und Kultur] in the imprint—are the statements on the DVA facility in Dachau and the history and context of the extensive operation, in which edible and medicinal herbs were primarily cultivated, researched, and distributed on a large scale, using up to a thousand forced laborers (concentration camp prisoners). Sudrow’s vivid descriptions and testimonies of the harsh working conditions of the prisoners and the specific research programs carried out at the plant facility, which was mainly managed according to biodynamic methods from April 1940 onwards, including Franz Lippert’s botanical studies, are also of lasting value. Sudrow has reconstructed these programs in their entirety for the first time.

The author sees the DVA facility in Dachau both as a center of scientific teaching and research in the field of organic farming and horticulture during the time of National Socialism, and also as a center of “alternative medicine” and the Reich Labor Association’s project for a “New German Art of Healing” [Reichsarbeitsgemeinschaft für eine “Neue Deutsche Heilkunde”]. With this assessment of medical history, she most likely overshoots her target; what is undoubtedly correct, however, is that the SS under Himmler understood itself as an elite group, had a mandate for operational settlement policy in the territories conquered by Germany, and wanted to carry out fundamental work and practical tests along these lines on its DVA estates. Among Sudrow’s primary interests were employees from the biodynamic movement who had different relationships with anthroposophy but were connected to it.

Prejudices

For Anne Sudrow, anthroposophical spiritual science, Rudolf Steiner’s life’s work, is nothing more than a “theosophical web of dogma.”4 According to her, Steiner, with his “authority as a clairvoyant,” did not actually teach anything; specifically, he did not teach any methodology, but instead relied solely on a mere esoteric “transference of knowledge,” which inherently excludes source criticism and contextualization.5 Even the Agricultural Course in Koberwitz near Breslau—the starting point for the Demeter initiative (June 1924)—was solely attended by “followers” and required a “profession of faith in anthroposophy.”6

For Sudrow, Steiner’s ideas and suggestions, including those in the field of organic farming, focus on “anthroposophical questions of faith.”7 The agricultural preparations and their production are also based on “quasi-religious affirmations.”8 According to Koberwitz, biodynamic farmers, in accordance with Steiner’s requirements, pursued “nature-mystic practices” and meditated while sitting in the fields of grain. The biodynamic farming method is an “occult version” of organic farming,9 characterized by a “speculative-esoteric approach”10 and is (to this day) only practiced by people who have previously undergone training in “anthroposophical beliefs and ways of thinking,”11 with “magical practices” and “superstitious uses of plants in the tradition of Paracelsus.”12

She writes that there has never been any original scientific activity in the field of biodynamic agriculture; rather, Steiner’s “faith community” was assigned the task of “communicating their own work to the rest of the world in seemingly natural scientific concepts in order to conceal its esoteric roots.”13 This was solely a matter of giving their work a natural scientific “veneer,”14 of “religious esotericism in the guise of science.”15 To this day, the preparations of the Demeter movement, like the entire practice of biodynamic agriculture, have, according to Sudrow, remained without any proof of effectiveness; open-ended studies have never been published. Rather, the entire movement works “esoterically” and in the tradition of “secret schools” with “hidden” knowledge, a “doctrine” into which “newcomers are initiated through a teacher-student relationship and through meditative techniques . . . .”16

All of Sudrow’s assertions have nothing to do with the historical reality and current practice of biodynamic agriculture, its work, its content, its methods, and scientific research. They distort and caricature reality beyond recognition—and defame the people working in this field worldwide.

. . . Part of a Questionable Tradition

Since Sudrow believes that people who engage with anthroposophy in theory and practice are tainted in some way, she consistently applies such labels to their work as “anthroposophical historians” and “anthroposophical biographers,” as well as all research projects sponsored by “anthroposophical foundations,” which therefore indicates they are not to be taken seriously, as they come from a sectarian subgroup of society and consequently do not serve the cause of finding the truth but rather of concealing or reinterpreting it. Consciously or unconsciously, Sudrow’s discriminatory prejudices are not only in line with contemporary criticism of anthroposophy but also with much older German traditions. Anyone who reads the reports of the SS security service on the surveillance of anthroposophists or suspected anthroposophy cases, or even just the last summary document of the Reich Security Main Office [Reichssicherheitshauptamtes, RSHA] on “Anthroposophy and its Special-Purpose Associations” [Die Anthroposophie und ihre Zweckverbände] (1941), will find not only Sudrow’s conceptions of Steiner’s occult “secret circles” and “secret teachings,” but also the conviction of influential anthroposophical “networks” striving for power and working underground in contemporary history.

What is not found in these reports, however, is Sudrow’s assertion that the Nazi rejection of anthroposophy was based on the fact that the anthroposophical worldview “was closely related to folkist ideas and exhibited overlaps with the social goals of the NSDAP [National Socialist Party].”17 All surveillance reports and Nazi expert opinions, including those of Alfred Baeumler, state the exact opposite—that anthroposophy rejects racial doctrine and does not discriminate according to biology or folk group but rather is individualistic, pacifist, and humanistic, as well as friendly toward Jews. According to the assessment of the Reich Security Main Office in 1941, “Based on these findings, it must be concluded that anthroposophy in all its forms—whether it be the Christian Community or an agricultural, medical, educational, or artistic method—presents a danger to the unified National Socialist orientation of the German people that cannot be underestimated.”18

Never Described in “Anthroposophical Studies”?

According to Sudrow, the fact that individual anthroposophists collaborated in DVA enterprises (in consultation with the leading officials of the Reich Association under the leadership of Erhard Bartsch and Franz Dreidax) was downplayed, reinterpreted, or “consistently concealed” in “all publications of anthroposophically commissioned research.”19 Sudrow confidently presents her study as the first “historical correction of the pure victim narrative of the anthroposophists,”20 who, as such, had no interest in clarification. Lippert’s free decision to collaborate in a leading position at the DVA Dachau has also been “turned on its head in anthroposophical studies.”21 Even Sigmund Rascher’s “close connections” to anthroposophy have “not been adequately taken into account” to date.22

Susanne zur Nieden, Meggi Pieschel, and Jens Ebert wrote a book entitled Die biodynamische Bewegung und Demeter in der NS-Zeit: Akteure, Verbindungen, Haltungen [The biodynamic movement and Demeter during the time of National Socialism: Participants, connections, approaches], after being commissioned as part of a three-year research project by the Section for Agriculture at the Goetheanum, Demeter Germany, and the Biodynamic Federation Demeter International. On July 2, 2024, at the Topography of Terror [Topographie des Terrors] in Berlin (with Anne Sudrow present in the auditorium), they presented their book, wherein they describe, in thoroughly detailed chapters, the path of biodynamic farmers in the Nazi state.23

Alongside much else, they show how Reich-influenced groups pushed forward with all their might the Nazi state’s dirigisme in agricultural policy and the industrialization of agriculture, demanded maximum yields and efficiency in the agricultural sector, advocated an aggressive national expansion policy, and saw the “food security” of the population as only being guaranteed by artificial fertilizers. Together with Nazi ideologues critical of anthroposophy, official experts, and representatives of the Gestapo and the SD [Sicherheitsdienst, “Security Service,” intelligence agency of the SS], these groups had been pushing since 1933 for a ban on the biodynamic “outsider and provocateur.” The Reichsnährstand [Reich Food Society], the professional organization for agricultural policy and economics in the German Reich, as well as leading agricultural scientists and the majority of the employees of the Ministry of Agriculture, all rejected biodynamic agriculture.

Confronted with this situation, and shortly before their ban, the biodynamic farmers and their association, led by Erhard Bartsch, attempted to establish relationships within the Nazi Party with circles that were critical of industry and artificial fertilizers, as well as with influential adherents of naturopathy and those lobbying for a “public health” based on the use of biological methods (purification processes using microorganisms) in party and government circles. They did, in fact, succeed and continued their work. After the start of World War II, Heinrich Himmler favored biodynamic farming as an option free of artificial fertilizers for estates in territories conquered in Eastern Europe, provided that it gave a positive result. Erhard Bartsch did not refuse this collaboration but saw promise in the opportunities for work and development, as Uwe Werner critically pointed out in 1999.24

In June 1941, following the Reich-wide Gestapo action against anthroposophy, many of the efforts of Demeter officials foundered, the Reich Association was banned, Erhard Bartsch and other farmers were imprisoned, and biodynamic agriculture no longer had a chance in agricultural policy. Still, Himmler stuck to his plan within the framework of his SS sovereignty over the DVA estates and, despite Heydrich’s veto, ensured that individual experts from the biodynamic movement carried out the conversion of the DVA estates and that their methods were tested there. Zur Nieden, Pieschel, and Ebert examined the serious problems of this collaboration in detail in their study, including the obscuring of the context of Lippert’s and Künzel’s Dachau plant research in publications after 1945. Of the twelve biodynamic experts described by Sudrow who worked for the DVA, ten were already known to zur Nieden, Pieschel, and Ebert, while Sudrow’s meticulous Dachau studies revealed two more individuals. However, zur Nieden, Pieschel, and Ebert are rightly far removed from the interpretation of these ten or twelve as a strategically operating “network of anthroposophists in the SS” (Sudrow), without in any way downplaying the problematic nature of their collaboration.

The Rascher Case

Contrary to Sudrow’s assertions, Sigmund Rascher’s connections to anthroposophy are not the only ones to be found in the first volume of the study Anthroposophische Medizin, Pharmazie und Heilpädagogik im Nationalsozialismus 1933–1945 [Anthroposophic medicine, pharmacy, and curative education under National Socialism] (commissioned by the Academy of the Society of Anthroposophic Doctors in Germany [Akademie der Gesellschaft Anthroposophischer Ärztinnen und Ärzte in Deutschland, GAÄD] and the Medical Section of the Goetheanum) on the basis of all source material available to date by P. Selg, S. H. Gross, and M. Mochner (in much greater detail than Anne Sudrow).25 The same applies to Rascher’s activities in the Dachau concentration camp (following Julien Reitzenstein and all the literature available on the subject to date).26

Rascher’s relationships with the anthroposophical drug manufacturer Weleda, his position within the anthroposophical medical profession, and his relationships with those who worked with Ehrenfried Pfeiffer and Lilly Kolisko’s natural scientific methods in the Dornach Glasshaus and other locations have also already been analyzed. As has been known for decades, Rascher had learned the method of “sensitive crystallization” during his medical studies in Basel while working with Ehrenfried Pfeiffer, and later used it to obtain a doctorate and publish two articles in the prestigious Münchener Medizinische Wochenschrift [Munich medical weekly], which aroused great interest in the circles of anthroposophical physicians and Weleda. Sudrow’s assertion that Pfeiffer’s methods had always been rejected in the academic natural scientific disciplines “due to a lack of conclusive empirical studies”27 is scientifically untenable.

Pfeiffer’s biological research methods can hardly be held responsible for the fact that Rascher came into close contact with Heinrich Himmler (via Rascher’s partner Karoline Diehl) in the spring of 1939 and became a concentration camp researcher conducting brutal human experiments; they have nothing whatsoever to do with Rascher’s freezing and high-altitude/low-pressure experiments on prisoners. Sigmund Rascher increasingly distanced himself from anthroposophy, which he had been introduced to in his parents’ home. During his time at the Dachau concentration camp, he reported his father, the anthroposophical doctor Hanns Rascher, to the Munich police, called in the Gestapo, and accused his father of having connections to the center of anthroposophy in Dornach28—most likely to protect himself, since Himmler wanted to try out biodynamic farming methods but (like Reinhard Heydrich) saw anthroposophy and Steiner as extremely dangerous factors.

Sigmund Rascher’s publications in the Münchener Medizinische Wochenschrift were known to anthroposophical doctors and Weleda, but they were also aware of his serious personality problems, which were already evident before his close relationship with Himmler, his entry into the SS research community Ahnenerbe [Ancestral heritage], and his start of work at the Dachau concentration camp, where he then became the “lord of life and death.” A boastful demeanor with traits of megalomania, a narcissistic need for recognition, and a latent propensity for violence, including threats involving Himmler and the Nazis, characterized Rascher’s few surviving correspondences with anthroposophically oriented physicians who kept their distance from him (and the SS).

Sigmund Rascher exchanged a few surviving letters with Weleda, which are not easy to interpret due to the lack of context; the documents do not suggest that Rascher played an “important mediating role” between the SS leadership and the anthroposophical “practitioners,” as Sudrow claims,29 but rather exactly the opposite. Likewise unfounded is the claim that “from 1939 onwards, empirical knowledge circulated between the Weleda enterprise and Rascher for his reports to Himmler and his experiments in the Dachau concentration camp.”30 Sudrow exaggerates a request made by Rascher to various biological pharmaceutical companies (including Weleda) in July 1939 regarding the effectiveness of a coal preparation that Heinrich Himmler was interested in.31

Sudrow’s assertion that Rascher’s work “clearly shows personal influences and professional references to developments and ideological premises of anthroposophic medicine,” as she also postulates in her assessment, and that Rascher’s work continues to be “used” in anthroposophic medicine,32 is also completely misguided. Only Rascher’s publications in the Münchner Medizinische Wochenschrift on the method of “sensitive crystallization” (Pfeiffer/Kolisko) are still included in relevant publication overviews. What else could be included?

Weleda during the time of National Socialism: “Extensive contacts with the DVA and the SS”?

According to Sudrow, Weleda used its “extensive contacts with the DVA Dachau and the SS” for its own procurement of raw materials—and reciprocally, the DVA saw Weleda’s orders as “recognition of the biodynamic character of its products.”33 This is simply not the case. According to Sudrow, the dissent between Weleda and Franz Lippert, who left Weleda and ended up in Dachau via a roundabout route, as described in the literature, was invented specifically to “distance and exonerate the enterprise and to conceal the reality of its numerous and diverse connections with the SS and the Dachau concentration camp.”34

In their 580-page study on Weleda (and WALA) during the Nazi era, published in July 2025, Selg, Gross, and Mochner document the impressive resilience of Weleda’s management under the difficult living and survival conditions of the Nazi state. Weleda maintained its corporate identity and idealistic goals, did not adapt the speech and diction of its company newspaper (with a circulation of up to 80,000 copies) and employee training courses to the premises of National Socialism and the “New German Art of Healing,” and, despite interrogations and company searches (due to the anthroposophical background of the company), went its own way, partly under the protection of the Swiss consulate. The Weleda management was extremely critical of the political relations of the biodynamic Reich Association under the leadership of Erhard Bartsch,35 as were large sections of the anthroposophical medical profession.36 Weleda’s disagreement with Franz Lippert was not fabricated, but did actually take place and had to do with Lippert’s dual role as head of the Weleda herb garden and as head of the information center for the Reich Association and co-worker of Bartsch.37

In April 2024 and July 2025, Selg, Gross, and Mochner published documents from the Weleda archives showing that Lippert wanted to come to Schwäbisch Gmünd with Rudolf Lucass, the DVA’s medicinal plant expert, in early 1942, four months after he started working in Dachau. The German Weleda management was not enthusiastic about this idea, but the visit probably took place nonetheless. A seed order for Echinacea angustifolia placed by Weleda with the DVA in Dachau (September 1941) and a free delivery of vine leaves from the Heppenheim subcamp (summer 1942) are sparsely documented and, along with the testing of a Weleda veterinary medicine on DVA properties and the delivery of frostbite cream in January 1943, form the narrow documentary basis of what Sudrow calls the “very diverse and numerous connections between the enterprise and the SS and the Dachau concentration camp.” Based on meeting minutes, it was possible to prove that Weleda’s commercial director, Fritz Götte, visited Franz Lippert at the DVA once and, upon his return, made extremely critical comments to the Weleda management circle—presumably about the reality of life at the DVA facilities with the forced laborers from the adjacent concentration camp.

Dealing With the Past

Despite intensive research, the exact circumstances surrounding the delivery of Weleda frostbite cream to Sigmund Rascher remain unclear to this day. However, it can be inferred that Götte and his colleagues in management expected Rascher to conduct an experimental efficacy test, as he had planned to compare different preparations for treating the effects of frostbite and submitted a corresponding research application on December 13, 1942.38 It is not clear whether the German leadership of Weleda was aware at the beginning of 1943 that Rascher was producing the freezing injuries himself, nor whether he ever used the preparations from Weleda (and other manufacturers) to treat the injuries.39 At the latest, four years after the delivery, in April 1947, Weleda was aware of Rascher’s cruel freezing experiments through the report on the Nuremberg Doctors’ Trial by Mitscherlich and Mielke.40 It is unclear how the company management then dealt with this; when confronted by Götz Aly in the early 1980s about their delivery of frostbite cream, they denied any knowledge of Rascher’s SS position, claiming that he had ordered the delivery to his private address.41

The reunion between Weleda leadership and Franz Lippert in early 1947 at a conference on biodynamic issues had already been fraught with tension. As documented by Selg, Gross, and Mochner, the Weleda leadership nevertheless concluded a temporary consulting contract with Lippert, whose expertise the company urgently needed. However, Sudrow’s assertion that the company leadership had no reservations whatsoever about collaboration with former DVA collaborators—Lippert and Künzel—after 194542 does not correspond to historical reality. In fact, there were considerable moral reservations; Lippert had heard of Götte’s criticism after his visit to the DVA and felt that Weleda handled him with mistrust because of his collaboration in Dachau—even though a former prisoner and forced laborer had personally vouched for him at Weleda, attesting to his extraordinarily humane and protective treatment of the prisoners. Shame and embarrassment were certainly present on the part of Weleda’s leadership (but apparently not on Lippert’s part); nevertheless, they decided to compromise with him, though this was short-lived. Götte refused to hire Lippert’s colleague in Dachau, Martha Künzel, because of her DVA activities but was interested in her Dachau research results in the field of plant breeding—and thereby entered into another compromise after 1945. The name Dachau was blacked out in documents—and after Lippert’s early death in 1949, the temporary rapprochement with the former head gardener was erased from the company’s memory.43

“Eco-Fascism” and Enemy Stereotypes

Dealing with the company’s history during the Nazi era and the dilemmas that Weleda faced despite its clear anti-Nazi stance and the compromises it made proved difficult for its leaders for many decades and until very recently. The company had not followed the path of resistance taken by the White Rose—and yet it was miles away from the behavior of the Nazi and concentration camp profiteers of the IG Farben complex and other German companies.44 Accused by parts of the press since the early 1980s of collaboration with “eco-fascism,” Weleda’s leadership shifted its focus to emphasizing its resistance to the Nazis, which ultimately did not help it—and missed the opportunity for a nuanced reappraisal of its own resistance and compromise. Thanks to Anne Sudrow and Der Spiegel, the company has once again come under media scrutiny, even though the anthroposophical pharmaceutical manufacturer is hardly mentioned in the 692-page Dachau monograph.

“Any errors in content remain my own,” writes Ms. Sudrow at the end of her study. It would have been nice if some of the “errors” and assertions she mentions had remained with her alone; however, it’s no accident that she presented and propagated them far and wide. There is an undeniable tragedy in the collaborative behavior of people like Erhard Bartsch, Franz Lippert, Martha Künzel, and others, even without their being guilty of any direct crimes, and even when there is no doubt that anthroposophy itself was harshly prohibited and even persecuted by the Nazi state. But there is also a tragedy in the case of a historian like Sudrow, who works fully committed to researching the time of National Socialism but who generates new, discriminatory enemy stereotypes with obvious aggression. This is deeply regrettable, given the important aspects of Sudrow’s commendable work on the DVA in Dachau, but also in view of the reputation of Weleda and Demeter’s work, indeed of anthroposophy in the public sphere. It is to be hoped that a differentiated reappraisal of the much more complex historical reality will ultimately prevail.

Translation Joshua Kelberman

Footnotes

- Stefan Hunglingern, “Ökoprodukte für Nazis” [Eco-products for Nazis], Der Spiegel, no. 37 (Sep. 5, 2025): 38–41.

- Anne Sudrow, Heil Kräuter Kulturen. Die SS, die ökologische Landwirtschaft und die Naturheilkunde im KZ Dachau [Healing herb cultures: The SS, organic farming, and naturopathy in the Dachau concentration camp] (Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2025).

- Götz Aly, Taz (May 19, 1983); Arfst Wagner, Dokumente und Briefe zur Geschichte der Anthroposophischen Bewegung und Gesellschaft in der Zeit des Nationalsozialismus [Documents and letters on the history of the Anthroposophical Movement and Society during the time of National Socialism], 5 vols. (Rendsburg: Lohengrin, 1991–93); Uwe Werner, Anthroposophen in der Zeit des Nationalsozialismus (1931–1945) [Anthroposophists in the time of National Socialism] (Munich: Oldenbourg, 1999); Jens Ebert, Tanja Kinzel, Meggi Pieschel, and Kristin Witte, Die Versuchsanstalt: Landwirtschaftliche Forschung und Praxis der SS in Konzentrationslagern und eroberten Gebieten [The Research Institute: Agricultural research and practice by the SS in concentration camps and occupied territories] (Berlin: Metropol, 2021); Jens Ebert, Susanne zur Nieden, and Meggi Pieschel, Die biodynamische Bewegung und Demeter in der NS-Zeit: Akteure, Verbindungen, Haltungen [The biodynamic movement and Demeter during the time of National Socialism: Participants, connections, approaches]. (Berlin: Metropol-Verlag, 2024); Peter Selg, Susanne H. Gross, Matthias Mochner, Antroposophie und Nationalsozialismus: Die anthroposophische Ärzteschaft [Anthroposophy and National Socialism: The anthroposophical medical profession], vol. 1. Anthroposophische Medizin, Pharmazie und Heilpädagogik im Nationalsozialismus 1933–1945 [Anthroposophic medicine, pharmacy, and curative education under National Socialism] (Basel: Schwabe, 2024); Weleda und WALA—die anthroposophischen Arzneimittelfirmen [Weleda and WALA—The anthroposophic pharmaceutical companies], vol. 2 (2025); Anthroposophische Psychiatrie und Heilpädagogik 1933–1945 [Anthroposophical psychiatry and curative education], vol. 3, (forthcoming, April 2026).

- See footnote 2: Sudrow, 593.

- Ibid., 513.

- Ibid., 56.

- Ibid., 564.

- Ibid., 59.

- Ibid., 567.

- Ibid., 611.

- Ibid., 253.

- Ibid., 314.

- Ibid., 593.

- Ibid., 511.

- Ibid., 25.

- Ibid., 512.

- Ibid., 80.

- Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiter-Partei. Schutzstaffel. Reichssicherheitshauptamt [National Socialist German Workers’ Party. Protection Squad. Reich Security Main Office], Die Anthroposophie und ihre Zweckverbände: Bericht ünter Verwendung von Ergebnissen der Aktion gegen Geheimlehren und sogenannte Geheimwissenschaften vom 5. Juni 1941 [Anthroposophy and its special-purpose associations: Report using the results of the action against secret doctrines and so-called secret sciences of June 5, 1941] (Berlin: Reichssicherheitshauptamt, 1941). 48.

- See footnote 2: Sudrow, 567.

- Ibid., 28, 237.

- Ibid., 552.

- Ibid., 645.

- See footnote 3: Ebert, zur Nieden, Pieschel, 111 ff; cf. Selg, Gross, Mochner (2024), 443–470.

- See footnote 3: Werner, 279 ff.

- See footnote 3: Selg, Gross, Mochner (2024), 651–670.

- Julien Reitzenstein, Himmlers Forscher [Himmler’s research] (Paderborn: Schoeningh Ferdinand, 2014).

- Sudrow, 331.

- Selg, Gross, Mochner (2024), 625.

- Sudrow, 646.

- Ibid., 646.

- Selg, Gross, Mochner (2024), 661 f.

- Sudrow, 647.

- Ibid., 541.

- Ibid., 547.

- Selg, Gross, Mochner (2025), 264–280.

- Ibid., 452–470.

- Ibid., 277–281.

- Ibid., 667.

- See footnote 26: Reitzenstein, 177.

- Alexander Mitscherlich and Fred Mielke, Das Diktat der Menschenverachtung: eine Dokumentation [vom Prozeß gegen 23 SS-Ärzte und deutsche Wissenschaftler] [The dictates of contempt for humanity: A documentary [on the trial of 23 SS doctors and German scientists]] (Berlin: Lambert Schneider, 1947).

- Cf. Selg, Gross, Mochner (2024), 339 f.

- Sudrow, S. 567.

- Cf. Selg, Gross, Mochner (2025), 329–341.

- Cf. Ibid., 69–81.

Thanks for your excellent article on Dachau, Demeter and Weleda, a tragic story. Given the resurgence of the Far Right in Europe and proto Fascism in the USA today, its important to understand how people resisted, and what led them to resist, so as to help current concerns, so we can be more resilient. What are the stories of anthroposophists resisting, rather than various forms of what can be seeb perhaps as collabouration? And how do these connect and compare with other groups? There are good resistance stories, often sadly forgotten ones, like the FAB revolt against the Nazis led by Ruprecht Gerngross and his translators during the fall of Munich, which spared the blanket Bombing of the city by the Allies, and news of the revolt indirectly saved some Dachau prisoners lives.