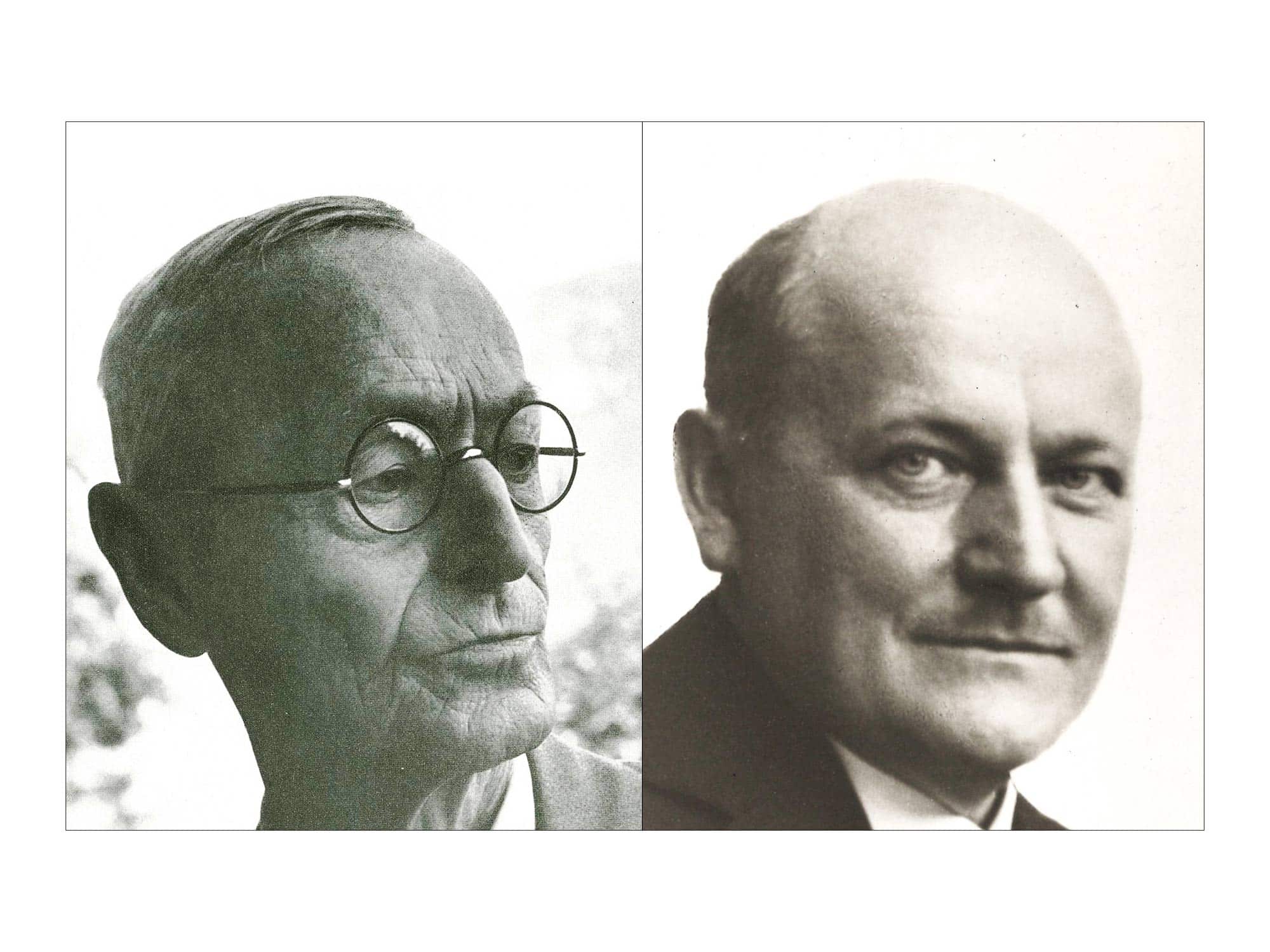

Cigarette manufacturer Emil Molt and writer Hermann Hesse were friends during their school days and became close again later in life, especially around the time of the founding of the first Waldorf School in 1919. However, Hesse did not seek a relationship with anthroposophy.

More than twenty years after their childhood friendship, Emil Molt and Herman Hesse established contact again. In a July 1919 letter, Emil Molt enthusiastically reported about the forthcoming founding of the Waldorf school: “We here are continuing to work faithfully. In one respect, we have now taken a serious step; some time ago, we set up a workers’ education school, the schedule of which I enclose here, and we are now proceeding to establish a free [independent] Waldorf school. It will be a unified school [Einheitsschule]1 in the best sense of the word, because children of the salaried employees and the proletariats will sit on the same benches and be taught by choice teachers of both sexes and different denominations. Chance brought us the beautiful Uhlandshöhe2 estate on Kanonenweg [today, Haussmannstraße], so that we will probably be able to start in September. We thereby want to make a practical start on this cultural issue and only hope that we succeed in carrying out the enterprise in the right spirit.”3

Patron of Hesse

After spending several years as schoolchildren at the same school in Calw, [Germany], they lost sight of each other for a long time. It was only their dispositions and activities during the war that brought them together again. During the time of positional warfare in the summer of 1915, Molt decided to supply the front not only with tobacco, but also with intellectual nourishment in the form of inspired reading. At the same time, he decided to support the Swabian poets and approached a number of artists, including Hermann Hesse, who was living in Switzerland at the time. The latter agreed to collaborate: “Your letter is signed by E. Molt; if this is my old school friend from Calw, please send him my regards.” This was not only the start of an extensive correspondence between Molt and Hesse but also of a passionate exchange on philosophical and ideological issues, and a sincere friendship that lasted another twenty years.

Molt discovered Hesse’s genius early on. He considered the then still relatively unknown poet to be a great intellectual power and diligently promoted the prisoner-of-war welfare program, which Hesse coordinated on a voluntary basis from Bern, [Switzerland] during the war years and which supplied the prison camps with suitable reading material. As a result of their friendship, Molt also became increasingly generous in supporting Hesse himself in his chronic economic hardship. In 1917, Hesse noted in his diary: “Molt is that rich friend whose guest I was in St. Moritz, [Switzerland] and on whom I am certainly dependent through loans, while he recognizes me as a mind and artist and often subordinates himself to me in conversation.” Molt also offered Hesse to set up a “Waldorf account” in his company for Hesse’s German income, to serve as his accountant, so to speak, which Hesse gratefully accepted.

Press for the Uhlandshöhe?

Less well-known is the fact that Molt tried to win Hesse over to his plans to renew the social organism out of the independent spiritual life in Stuttgart in 1919. Molt was probably thinking less of the role of a teacher in the new Waldorf school, and rather more of the role of an editor or journalist in his public relations work. Hermann Hesse also distinguished himself as a writer by excellently and profoundly describing the nature of childhood and youth, for example, in his stories Beneath the Wheel or “Childhood of the Magician.” He, himself, painfully experienced the distress of children, being misunderstood in their needs by adults, and also the inability of educational institutions to take this into account. In 1919, an opportunity arose for Hesse to work on an educational enterprise that was probably very close to his own childhood experiences and insights into the nature of children.

Thus, Molt reported to Hesse at the beginning of the working out of the threefold ideas, near the end of 1918: “Work a plenty, and we are all looking forward to your collaboration.” Molt was able to motivate Hesse to sign the threefolding “Appeal to the German People and Cultural World”4 in February 1919, and he also wrote smaller texts for the Waldorf Nachrichten [Waldorf News]. However, Hesse was unable and unwilling to contribute more. In 1919/20, he found himself in a very deep personal and family crisis. As much and as sincerely as Hesse appreciated and admired Molt’s initiatives and was also interested in some of them, Hesse was, on the other hand, completely preoccupied with his own affairs and did not find an approach to anthroposophy. Even if some benevolent remarks about Rudolf Steiner can be found here and there in Hesse’s letters and works, on the whole, anthroposophy remained an unsatisfactory substitute for religion for him, a faith with too strong a connection to its founder.

In June, for example, he wrote to Molt: “My task lies on the side of the spirit, not of practice, and therefore also not of politics. I see ever more connections between current events and the thoughts about the European spirit and decline that I already had before the war.” Or a few weeks later, after Molt had obviously not let up in his enthusiasm and continued to try to draw Hesse in further, Hesse wrote clearly: “I have confidence in all your great and beautiful plans and wish you luck with all my heart! I myself am determined to stand further away and hold my distance. I understand your demands, but they do not speak to me personally in the same way, as I am completely absorbed and consumed by my task . . . . I often think of you all, and you, and of your new school, which I am especially happy about. Believe me, I would like to be closer to you. But, I am fighting for my life here and must continue to grow my yearly rings in silence.”

Distant Interest

Molt’s few surviving letters to Hesse testify to great, but, as it turns out, unrealistic hopes and a patience that would not tire: “I hold much in promise for your current external and internal work and long for the time when I can really talk to you again—surely very valuable things will sprout from this work, and I am convinced that this development, all by itself, will lead you even more to Dr. Steiner.” This conviction was, however, wrong and proved to be illusory. Hesse remained indifferent or even skeptical about Steiner until the end of his life.

Molt, nevertheless, stood up for Hesse, supported him generously, and offered to look after his sons during his severe family crisis. Hesse separated from his wife, who was undergoing psychiatric treatments off and on and placed his three sons with friends or in care homes. The eldest son, Bruno [1905–1999], was only a few months older than Molt’s son, Walter. In January 1920, Hesse referred to Molt’s offer: “The most important thing for me is that you (along with my sister Adele in Höfen) are there as a friend and advisor for my boys! At the moment, things are not looking good for the older one, Bruno, who, it seems, is reluctant to go to the new place and worries the teacher. Should it come to the point where the teacher holds that it would be better to separate the boys, I would authorize him to contact you. In that case, would it perhaps be possible to bring Bruno to your school?” But, Bruno never became a Waldorf pupil; he was taken into the family of the [Swiss] painter Cuno Amiet [1868–1961] beginning in April 1920 and later became a painter himself.

Just as Hesse applauded Molt’s initiatives from the distance of his domicile in Ticino, [Switzerland] (“I read about your splendid school with commiseration and a loud bravo!”), he concluded his comments on April 1, 1920, with a final small but clear remark on his relationship to the anthroposophical activities in Stuttgart: “I am delighted with the success of your school! Indeed, I am outwardly distant from this struggle, as I not only do not wish to be involved in any kind of organizational or educational activity but also do not know how to reconcile it with my actual life task, which is a very personal one. Nevertheless, I am very interested in your beautiful enterprises, and I am happy about every good beginning of the new, concerning which our people, the government first and foremost, determine with such difficulty and inertia.”

Translation Joshua Kelberman

Images From left to right: Hermann Hesse, Emil Molt

Footnotes

- A “unified school” [Einheitsschule] refers to the German school model that includes all groups of students, regardless of academic path or family situation, in contrast to other models, including, for example, farmer/peasant schools, worker/bourgeois schools, and pre-university schools (related to the Gymnasiums) [Bauern-, Bürger- und Gelehrtenschulen], which were exclusively attended by students from different family situations or prepared students for specific academic paths—Trans. note.

- The Uhlandshöhe is a hill in Stuttgart, Germany, named after the Uhlandshöhe Park, one of the largest areas of greenery in Stuttgart. The First Waldorf School was opened on the Uhlandshöhe on Sept. 7, 1919—Trans. note.

- All quotations in this text (not otherwise listed) are taken from the correspondence between Emil Molt and Hermann Hesse in the Deutschen Literaturarchiv [German Literature Archive] in Marbach am Neckar, Germany. For a detailed account of the relationship between Hermann Hesse and Emil Molt, see Elke Schlösser and Tomas Zdrazil, “Kindheits- und Jugenderlebnisse von Hermann Hesse und seine Freundschaft mit dem Schulgründer und Hesse-Mäzen Emil Molt” [Hermann Hesse’s experiences of childhood and youth, and his friendship with the school founder and patron of Hesse, Emil Molt] in Hermann Hesse Jahrbuch [Yearbook] 16 (2024): 139–156.

- Published March 15, 1919, as a leaflet and in various newspapers in Germany, Austria, and Switzerland. Rudolf Steiner, “To the German People and the Civilized World” in Rudolf Steiner, Towards Social Renewal: Rethinking the Basis of Society, CW 23 (Forest Row, East Sussex: Rudolf Steiner Press, 2000).