Theoretical physicists have long argued that time is not real—that it is an illusion.1 This view logically follows the conception of space and time as a unified, four-dimensional “space-time continuum,” introduced by Hermann Minkowski and used by Albert Einstein to formulate his theories of relativity. Because the General Theory of Relativity has not yet been successfully combined with quantum theory into a unified “theory of everything,” some physicists have seriously considered abolishing time as a reality. This position makes sense if the world is thought of as purely physical because then, indeed, there is no time. Experience, however, teaches us that the world we live in cannot be understood as merely physical and that time does exist. There is thus a need for a science that goes beyond purely physical methods to gain insight into those domains where time is a reality. Anthroposophy is such a science.

Abolition of Time in Favor of “Space-Time”

When mathematician and physicist Hermann Minkowski presented his idea of a four-dimensional space-time continuum at the 80th Natural Researchers’ Assembly in Cologne on September 21, 1908, he began with the words:

Gentlemen! The views of space and time which I wish to lay before you have sprung from the soil of experimental physics and therein lies their strength. They are radical. Henceforth space by itself, and time by itself, are doomed to fade away into mere shadows and only a kind of union of the two will preserve an independent reality.2

Minkowski then presented what has since been referred to as the space-time continuum or spacetime—a concept which Albert Einstein used shortly thereafter to formulate his theories of relativity. It is a four-dimensional mathematical space for events that are defined by four numbers, three (for example, x, y, and z) for the location in three-dimensional space and one (ct or ict) for time. This latter number is special: while x, y, and z are spatial variables, t stands for time, or more precisely, for a parameter t with the designation “time.” This becomes a spatial quantity, ct, when multiplied by the constant c (the speed of light in a vacuum). This artifice makes it possible to mathematically combine space and time as spatial quantities into a four-dimensional “space” composed of the components x, y, z, and ct (or ict). Minkowski’s earlier definition used ict with the imaginary unit; today, spacetime is usually defined with the real ct instead of the complex ict. In both cases, the special role of the component ct or ict has consequences for determining “distances” between events in this spacetime.

Assuming that the effects of (causative) events can never propagate faster than the speed of light in space, a distinction is made between different types of event distances: “spacelike,” when no causal relationships between two events are possible; “timelike,” when causal relationships between two events are possible; and “lightlike,” as a borderline case between spacelike and timelike distances when causal connections between two events are only possible at the speed of light. This is based on the assumption that causal relationships are temporal relationships or cause them, and that causes must precede their effects in time—and that effects must follow their causes in time. Kant needed causality to explain the direction of time; in spacetime, causality is used to distinguish between spacelike and timelike relationships. However, the four dimensions of spacetime ultimately have a spatial character in that all points on each of the axes, including the ct axis, are compatible with each other in terms of their simultaneous existence—they coexist with each other, which cannot be said of real points in time.3

Peter Christian Aichelburg, professor emeritus of theoretical physics at the University of Vienna, therefore characterizes space-time as something fixed: “Space-time is something like a timetable; everything is predetermined and unchangeable. However, how we incorporate the temporal aspect into the timetable is arbitrary. It’s our decision.”4 Albert Einstein was aware of one of the consequences of his theory: time becomes an illusion. In 1955, a month before his own death, when his friend Michele Besso had died, he wrote in a letter of condolence to Besso’s wife and son: “For us believing physicists the distinction between past, present, and future is only a stubbornly persistent illusion.”5

Logic as Reason for the Abolition of Time

In the same year that Hermann Minkowski introduced four-dimensional space-time, philosopher John Ellis McTaggart argued, based on principles of logic, that time was “a complex concept with two different logical roots” that he considered incompatible, and that it was unreal. He described different types of time as logically different series: an “A series” with past, present, and future, and a “B series” that contains an order of events according to “earlier” and “later,” but does not recognize past, present, and future. The A series can be described in the conventional sense of the word as subjective time: how world events are experienced by humans. The B series can be described as objective time, measured with clocks and processed mathematically, and thus corresponding to the objectification program of the natural sciences. In addition, McTaggart described a “C series” which could be described as “timeless time,” containing only the structure of the B series but not its property of change, its flow of time. Since the A and B series are logically incompatible but interdependent (the B series presupposes the A series), McTaggart saw no way out but to declare time as a whole to be unreal. The title of his essay is “The Unreality of Time.”6

Using McTaggart’s time series, philosophers Brigitte Falkenburg and Gregor Schiemann examined the most important concepts of time in physics, neurobiology, and philosophical phenomenology and came to the conclusion that a unified reductionist concept of time is implausible, notwithstanding the fact that many concepts of time seem unsatisfactory from an ontological point of view.7 Falkenburg deplores the current state of science with its justifiably differing and sometimes incompatible views of time. An understanding of time or a scientifically satisfactory description across all disciplines is not within sight. The relevant chapter in her book on brain research Mythos Determinismus: Wieviel erklärt uns die Hirnforschung? [The myth of determinism: How much does brain research explain?] is entitled “Das Rätsel Zeit” [The riddle of time].8 The conclusion: we cannot understand time with natural scientific and philosophical ways of thinking.

Rudolf Steiner described learning to understand time and overcoming the deception we succumb to with regard to temporal relationships as one of the important challenges currently facing humanity. Just as the illusion of perspective regarding spatial relationships was overcome at the beginning of the modern era—so we no longer succumb to deception and can correctly assess spatial relationships—the true temporal relationships about which people are currently deceived must be correctly recognized in the future.9

Quantum Gravity: Yet Another Reason to Abolish Time

Another motivation for abolishing time arises from the incompatibility of the different concepts of time in general relativity (gravity theory) and quantum theory. Science journalist Ulf von Rauchhaupt writes in a book review:

However, even physicists’ knowledge is still fragmentary. And the biggest gaps are actually in the question of time. This is because it is closely related to the problem whose solution is sometimes referred to as the “theory of everything.” How can Einstein’s theory of gravity, which has proven itself in the macrocosm, be reconciled mathematically with the quantum physics that governs the submolecular world? Attempts to construct such a theory of quantum gravity have already worn out several generations of theorists—and this is not least due to the completely incompatible concepts of time: In quantum physics [usually formulated on a fixed spacetime background], physical events remain embedded in an external time sequence, just like the chairs and stones of our perceptible world. But, in gravitational theory [general relativity], time is no longer an external clock but changes according to what happens within it [as part of the dynamical spacetime fabric].10

In order to preserve the ideal of a unified physics in which all subfields have a place and are compatible with each other, some scientists declare the physical world to be a “block universe” in which time does not exist as a flowing entity.11 They conceive of world events in accordance with spacetime as a four-dimensional “block” in which all points in time (indistinguishably past or future) are constantly present in reality. The ct axis of four-dimensional space-time no longer has anything temporal about it; time is conceived spatially. What we experience as temporal is declared an illusion.

Consequence of a Physicalist or Materialist Worldview

Declaring time to be an illusion is plausible and consistent for proponents of a physicalist or materialist worldview, for the following reasons. First, in a world conceived as purely physical, there is no way to determine via purely physical means where the present is to be situated in the four-dimensional block. The possibility of distinguishing between past and future is eliminated since the boundary between the two cannot be determined. Thus, no past, no present, no future. Secondly, in a purely physical world, there is no way to determine what the flow or passing of time is supposed to consist of according to purely physical terms. So, all points in time, wherever they may be in the past, present, or future, are perceived as equally given and real and thus deprived of their temporal character. In a consistently physicalist or materialist worldview, there is no flow of time, no change, and no present.12

The Clock and Time: Humans Establish the Relationship

Time is usually measured with clocks. But what do clocks have to do with time? They are mostly composed of solid, inorganic components. Their functioning can be understood using the laws of physics (mechanics, electrodynamics). For example, we understand every single process in a mechanical clock by interpreting the change in the magnitude of motion of a part we observe (“impulse,” mass times velocity) as the effect of forces that are not directly observed, whose (vector) sum is understood as the cause of the change in motion. This is expressed in the formula “force equals mass times acceleration.” “Mass times acceleration” is actually the change in momentum (impulse) over time, while “force” represents the sum of all forces acting on the mass in question at that moment. Curiously, the effect (the change in momentum) does not occur after the cause (the sum of the forces acting at that moment), but simultaneously. There is no temporal sequence of cause and effect. Both cause and effect occur locally in the same moment.

In an entirely different context, Rudolf Steiner distinguished the kingdoms of nature on the basis of, among other things, the simultaneity or temporal precedence of causes in the physical and superphysical realms:

- Mineral kingdom: Simultaneity of causes, within the physical.

- Plant kingdom: Simultaneity of causes, in the physical and super-physical.

- Animal kingdom: Past super-physical causes, corresponding to present effects.

- Human kingdom: Past physical causes, corresponding to present effects in the physical.13

The equations of motion in classical mechanics (mineral realm, inorganic nature) also reveal the simultaneity of causes and their effects in the physical realm. Due to the simultaneity of causes and their effects, there is only one type of timeless, permanent state of being for the purely mechanical function of the clock, without any relation to any real point in time. The clock has no relation to time unless a human being establishes this relationship by using the clock in a meaningful way with their human abilities of conscious perception, thinking, and understanding.

We Don’t Understand Time, But We Experience It

We experience the reality of time through our soul activities. All conscious soul activities take place in time and are experienced temporally. When a person observes a clock, they establish a relationship between the clock and time through their conscious soul activities of perception, memory, conceptualization, thinking, feeling, and willing. This fact is often overlooked: humans are necessarily involved when time is measured using clocks. The natural scientific objectification of time through measurement is based on a mental achievement of the spirit and soul of the human being. Brigitte Falkenburg arrives at a similar conclusion by other means: “Physical time with its direction is an empirically well-supported theoretical construct, but its theoretical foundations are neither unified nor fully understood. In this respect, the objective time of physics is a mental achievement of physicists, and its intersubjective use in human society is an enormous cultural achievement of humanity.”14

Time Is Not of This World

Time is not physical and therefore cannot be found in the physical world (the world of sensory experiences). We have no special sense of time like our sense of touch, taste, etc. Some physicists consider it an illusion, which, within a purely physical framework, cannot be successfully countered. And yet, time is a fundamental fact of human experience. If this cannot be appreciated by a materialistic natural science, then we need a different science. One such science is anthroposophy; it provides tools that enable the soul to explore areas of reality other than the physical, namely, the spiritual and the soul itself. At a time when Einstein’s special theory of relativity had been under controversial discussion for a couple of years and his general theory was yet unfinished (he published his “Entwurf einer verallgemeinerten Relativitätstheorie und einer Theorie der Gravitation” [Draft of a generalized theory of relativity and theory of gravitation] in 1913 but had to revise it and did not publish his “Zur allgemeinen Relativitätstheorie” [Towards a general theory of relativity] until the end of 1915), Rudolf Steiner wrote the following:

Insofar as man only considers himself within the realm of natural things and natural processes, he will not be able to escape the conclusions of this theory of relativity. There is no escaping the theory of relativity for the physical world, but precisely because of this, we will be driven to spiritual knowledge and cognition. The significance of the theory of relativity lies in demonstrating the necessity of spiritual knowledge, which is sought independently of natural observation by spiritual means.15

Four Levels of Realities of Time and the Fourfold Structure of Human Beings

Anthroposophical spiritual science distinguishes between different realms of reality in which human beings participate in specific ways. In these realms, time has different degrees of reality. Only human beings endowed with an ‘I’ are able to say “now” and to grasp and determine the meaning of the present moment by virtue of their spiritual, soul, and bodily presence. In this respect, uttering the word “now” is a performative speech act that actually creates the reality of a presently occurring moment in the act of speaking. The meaningful use of this word is only possible for an ‘I’-being: only the active presence of the ‘I’ in the physical world determines the now.

The flow of time is different. This is present to all beings capable of soul experience. Every being that has a conscious soul experience lives in time. The flow of time takes place within soul experience; it is a soul reality. “You only experience time in soul experience. But there you truly experience time . . . . There, time is a reality.”16 Following the present-forming impulse of the ‘I’ and the conscious soul experience of the flow of time, another layer of the reality of time is life itself, which encompasses all life processes of the human, animal, and plant realm, and the entire Earth. Interestingly, one’s “life” is also used as a term for biographical time. The part of the human being that sustains the life processes and can be thought of as the “architect” of the physical human being is referred to by Rudolf Steiner as the “life body,” “body of formative forces,” “etheric body,” or “time body.” As long as a human being lives, this time body permeates the physical body and sustains the life processes. Rudolf Steiner characterizes the difference between a living human being and a corpse as follows:

Why does [our physical body] actually perish? Why does it disintegrate? It begins to disintegrate when we die; before that, it did not disintegrate, it remained intact. Why? Because before that, we carry time within us. At the moment of death, the corpse is only in space; it cannot participate in time. The fact that it cannot participate in time, that it is only in space and has its lawfulness in space, makes it dead and causes it to die. We become corpses because of the impossibility of carrying time within us; during our earthly life, we live through the possibility of carrying time within us, of letting time work within us, of having time be effective within the substance extended in space.17

The fourth layer of reality is the physical world, in which time, strictly speaking, is not detectable. What relationship do inanimate physical bodies have to time? Solid bodies can be moved; liquids and gases are constantly in motion and changing. They owe this ability to the fact that they are embedded in time. Physical objects do not stand alone in space but are everywhere embedded, enveloped by the world ether—the “substance” of which time is made. By floating along in time, everything inanimate and physical can passively participate in the life of the world and move along with it. This embeddedness in real time affects not only inanimate things but all realms of nature, and especially humans, who develop a sensitivity to this non-physical environment.

Time, in its course, becomes something living, in a sense. More and more, one notices that one perceives life as differentiated in the course of time. Just as the individual organs in the physical body appear differentiated, becoming more alive inwardly and more independent of one another, so the parts of the continuous sequence of time become more independent of one another, in a sense. And this is thereby connected with the fact that, with the development of one’s own etheric body, one experiences life in the outer ether, which, indeed, everywhere surrounds us. It is not only the air that surrounds us; the ether also surrounds us everywhere and this ether lives a real life in time.18

In our fourfold structure, human beings show the same levels of differentiated reality as time does: a spiritual core, which expresses itself in the self-designation of the ‘I’; a soul-spiritual component, which in anthroposophy is called the “astral body”; a spiritual life-forming organism, which is called the “etheric body” or “time body” and is the “architect” of the physical body; and the physical body, which enables the presence of the human being in the physical world. Through their presence in the physical world, human beings demonstrate the reality of the spirit, of the soul, and of time. Human beings are the living proof of the reality of time.

Translation Joshua Kelberman

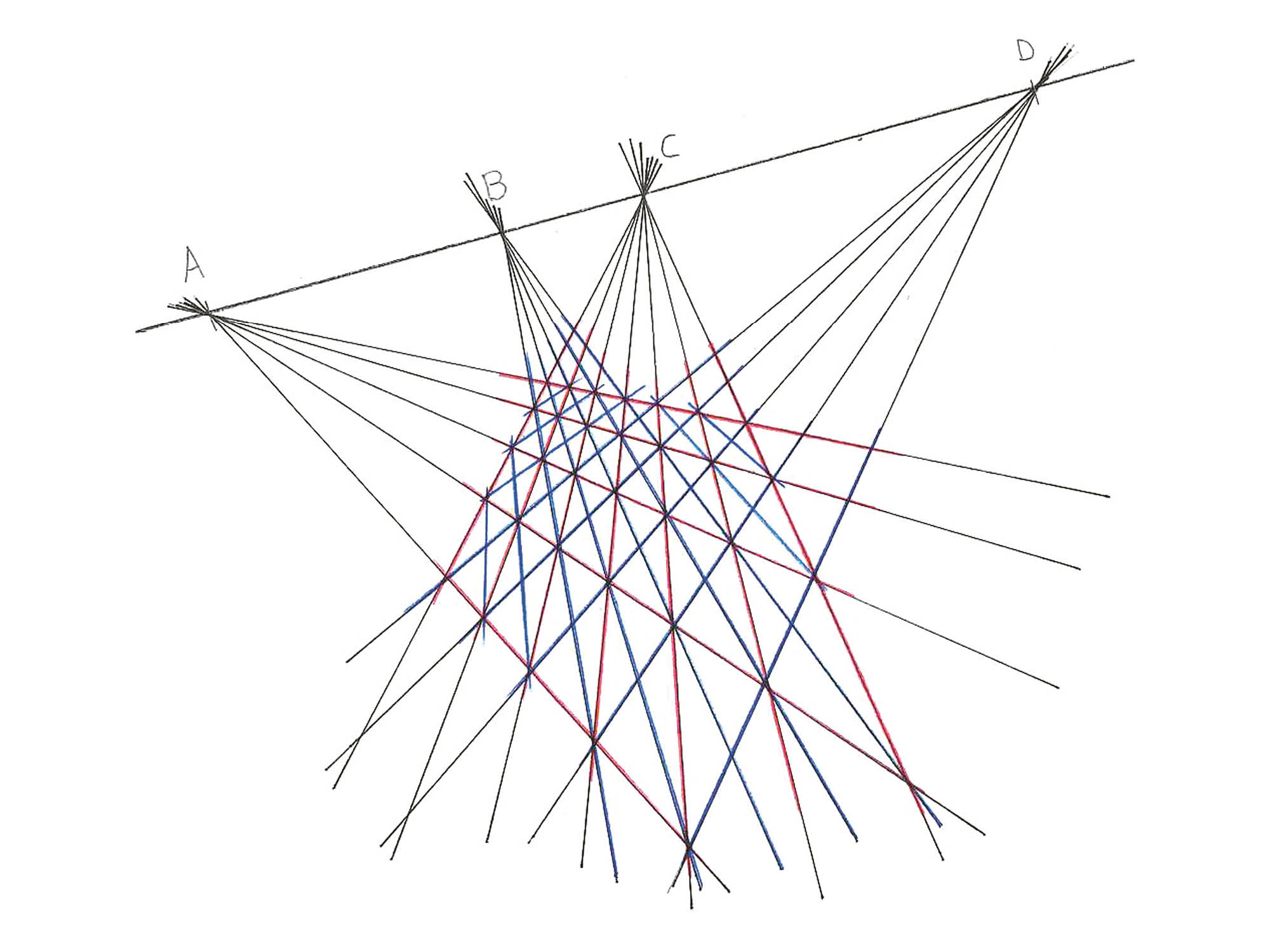

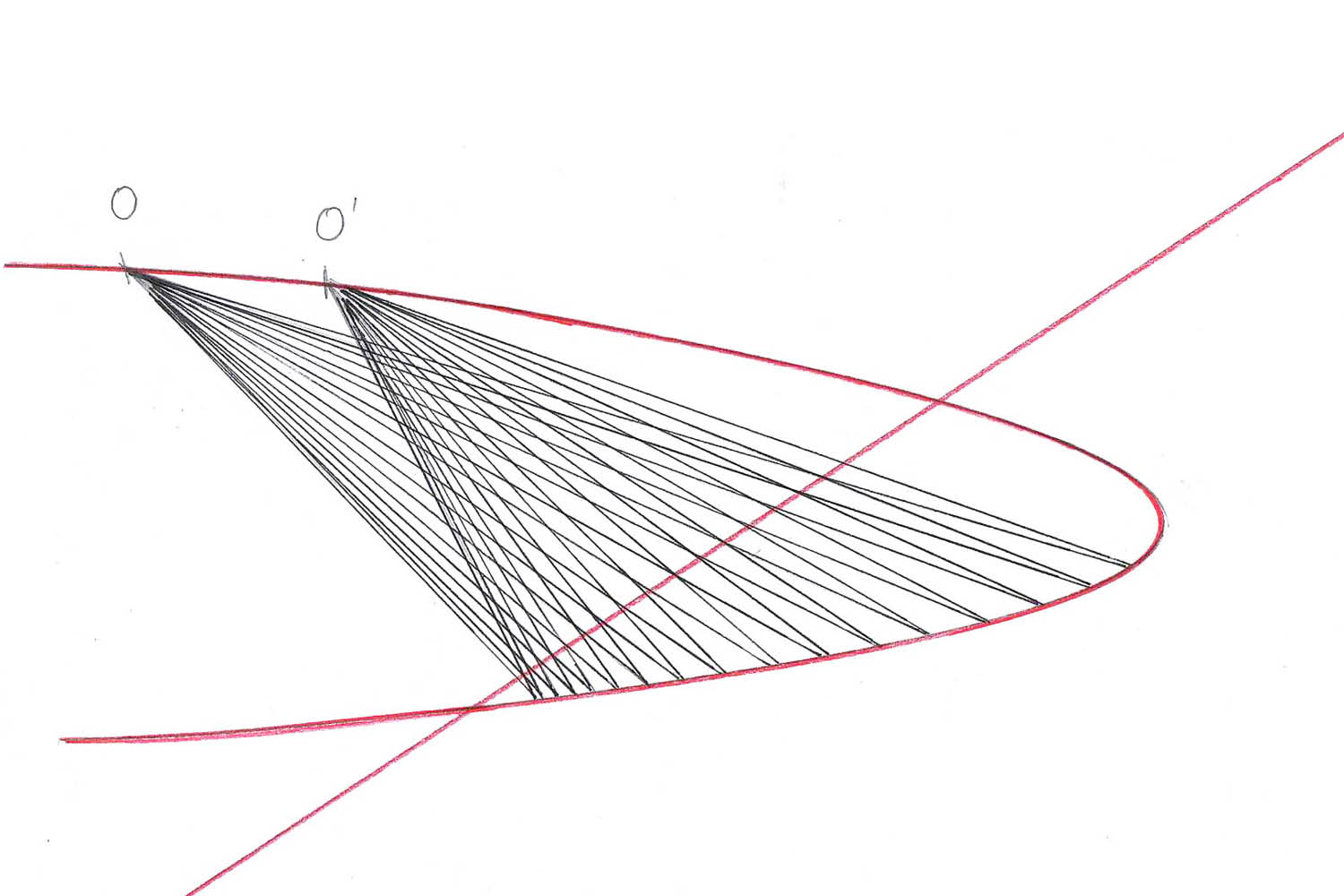

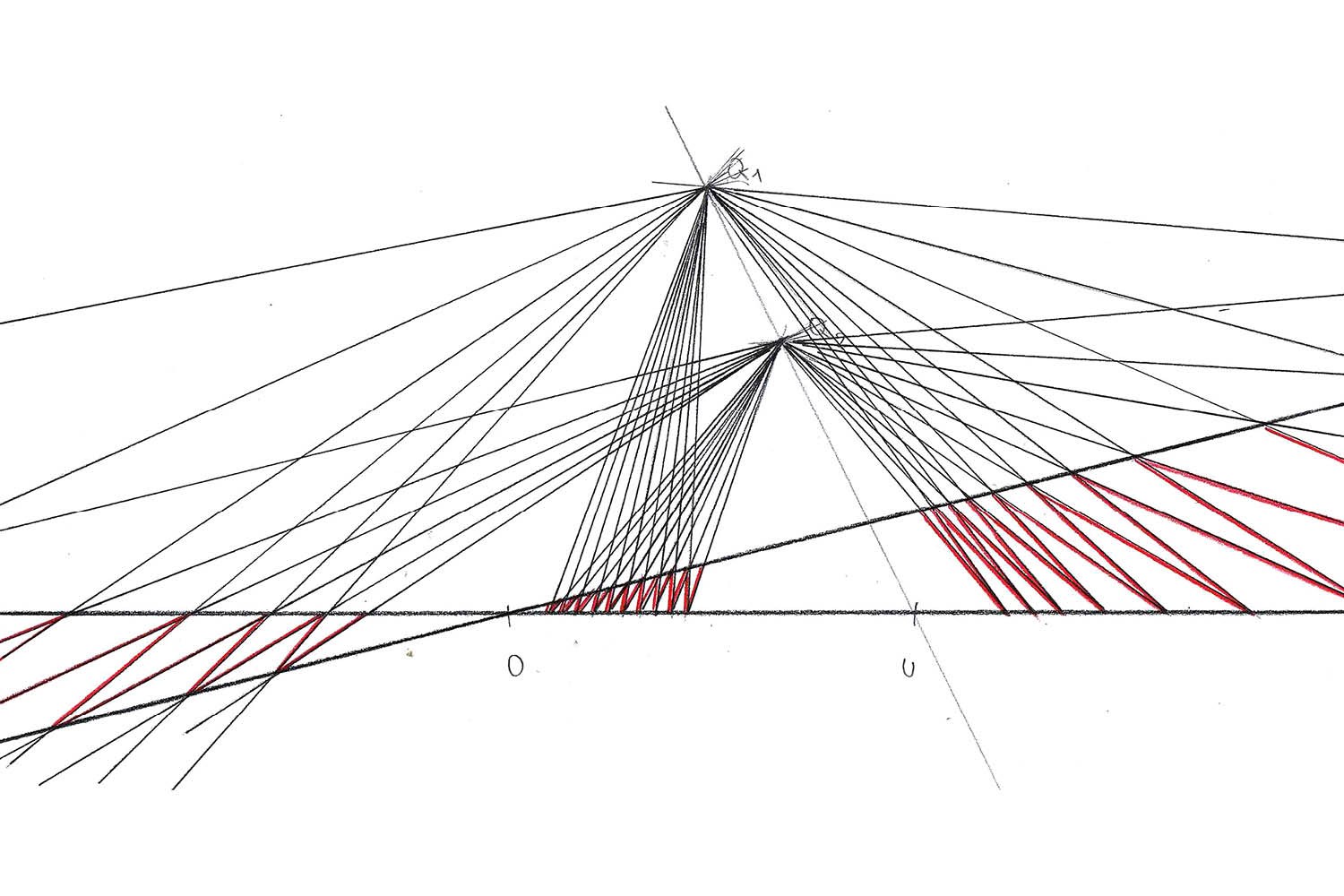

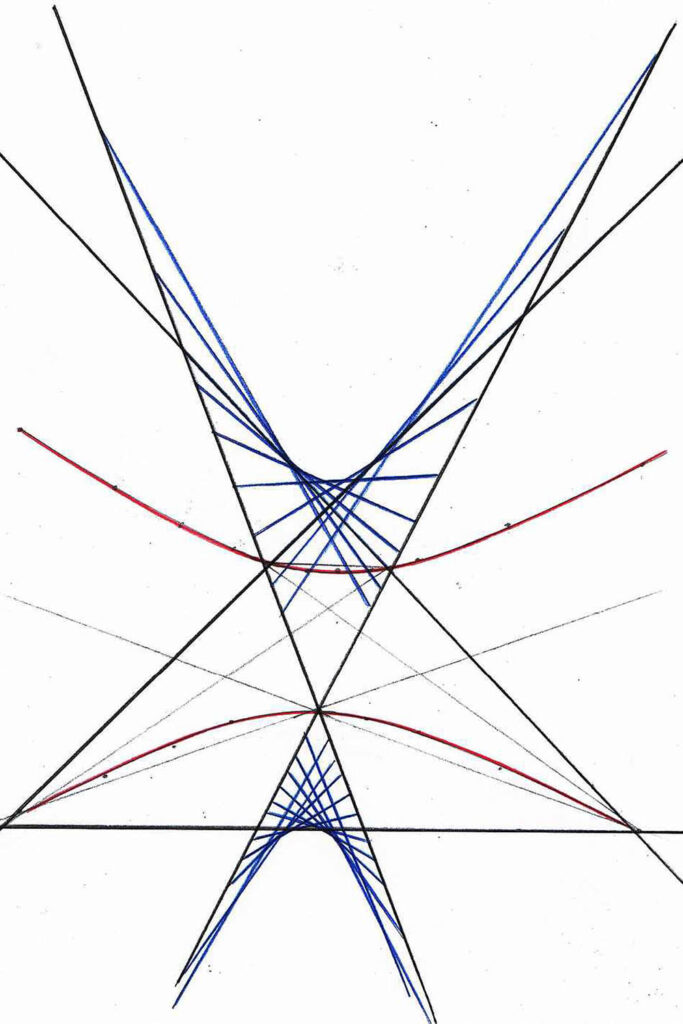

Illustration Projective geometry by Christina Moratschke. More at: Aurora Impuls and The Goetheanum: Section for Mathematics and Astronomy

Footnotes

- Craig Callender, “Is Time an Illusion?,” Scientific American 302, no. 6 (June 2010): 41–47.

- Hermann Minkowski, “Space and Time,” in The Principle of Relativity: A Collection of Original Memoirs on the Special and General Theory of Relativity, translated by W. Perrett and G. B. Jeffery (London: Methuen, 1923), 73–91; first published in German as H. Minkowski, “Raum und Zeit,” Physikalische Zeitschrift 10 (1909): 104–111; delivered as a lecture at the 80th Assembly of German Natural Scientists and Physicians, Cologne, Sept. 21, 1908.

- Rudolf Steiner, Nature’s Open Secret: Introductions to Goethe’s Scientific Writings (Great Barrington, MA: SteinerBooks, 2000), ch. 16.2, “The Archetypal Phenomenon,” and 16.5, “Goethe’s Concept of Space.”

- P. C. Aichelburg, “Die Raumzeit ist wie ein Fahrplan” [Space-time is like a timetable] Interview with Peter Christian, science.ORF.at (Jan. 15, 2010).

- Albert Einstein, letter to the Besso family, March 21, 1955, Einstein Archive 7–245, in The Quotable Einstein (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1996), 61.

- J. E. McTaggart, “The Unreality of Time,” Mind 17, no. 68 (Oct. 1908): 457–474; cf. Brigitte Falkenburg, Mythos Determinismus: Wieviel erklärt uns die Hirnforschung? [The myth of determinism: How much does brain research explain?] (Berlin: Springer, 2012), 214; new edition 2024.

- Brigitte Falkenburg & Gregor Schiemann, “Too Many Conceptions of Time? McTaggart’s Views Revisited,” in Time and Tense: Unifying the Old and the New, edited by Stamatios Gerogiorgakis (Munich: Philosophia, 2016).

- B. Falkenburg 2012, pp. 211–265.

- Rudolf Steiner, Human Evolution: A Spiritual–Scientific Quest, CW 183 (Forest Row, East Sussex: Rudolf Steiner Press, 2014), lecture in Dornach, Sept. 2, 1918.

- Ulrich von Rauchhaupt, “Quantengravitation: Die Abschaffung der Zeit” [Quantum gravity: the abolition of time] Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung (February 27, 2009).

- Julian B. Barbour, The End of Time: The Next Revolution in Physics (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999).

- Ibid.

- Rudolf Steiner, Karmic Relationships, Volume 1: Esoteric Studies, CW 235, translated by George Adams, revised by M. Cotterell, C. Davy, and D. S. Osmond (London: Rudolf Steiner Press, 1972, repr. 2012), lecture in Dornach, Feb. 16, 1924, p. 24.

- B. Falkenburg 2012, p. 261.

- Rudolf Steiner, Riddles of Philosophy, CW 18 (Great Barrington, MA: SteinerBooks, 1973, repr. 2009), pt. 2, ch. 7, “Modern Man and His World Conception”; first published in German in 1914, revised 1918.

- Rudolf Steiner, Rudolf Steiner, Festivals and Their Meaning (Forest Row, East Sussex: Rudolf Steiner Press, 1981, repr. 1996), part of the lecture series “Karmic Relationships,” given in Dornach, June 4, 1924, from GA 236.

- Rudolf Steiner, Eurythmy as Visible Singing, CW 278 (Forest Row, East Sussex: Rudolf Steiner Press, 2020), lecture in Dornach, Feb. 21, 1924.

- Rudolf Steiner, The Effects of Esoteric Development, CW 145 (Hudson, NY: Anthroposophic Press, 1997), lecture in The Hague, March 23, 1913.