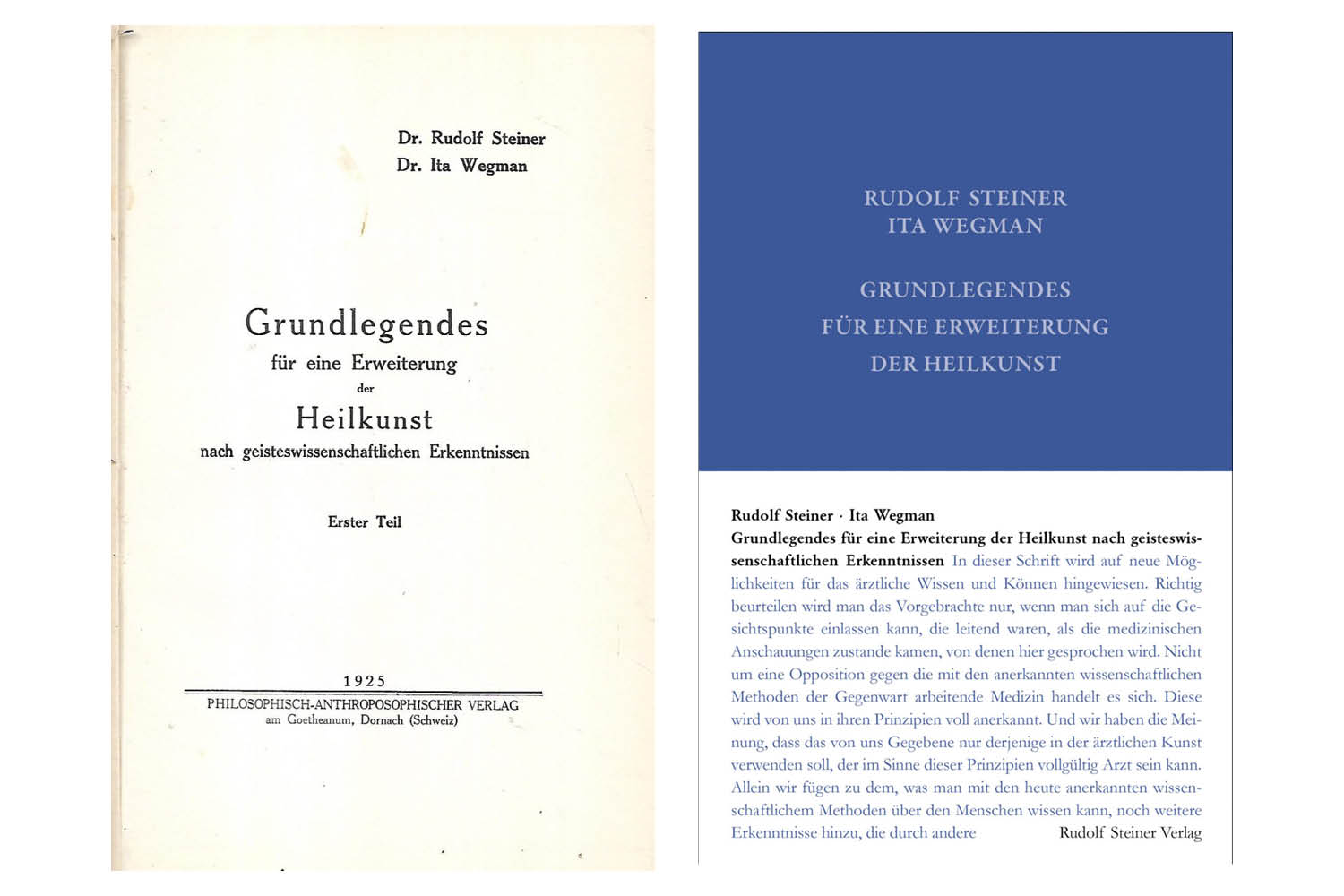

The 2025 annual conference of the Medical Section will focus on Rudolf Steiner’s book Extending Practical Medicine: Fundamental Principles Based on the Science of the Spirit. Wolfgang Held spoke with Karin Michael, co-director of the Medical Section, about this late work by Rudolf Steiner.

Wolfgang Held: Extending Practical Medicine is the only book that Rudolf Steiner co-authored, yes?

Karin Michael: I don’t know of any other. This shows me that, when he wrote this book, it was essential for him to be in dialogue with someone working in the professional field. He needed a counterpart with experience in the practice of medicine and was actively involved in it. He found that in Ita Wegman. There was also Ehrenfried Pfeiffer, whom he consulted repeatedly on the scientific knowledge of the time. In 1923, in Penmaenmawr, Ita Wegman asked Rudolf Steiner about a renewal of the Mysteries, and this question probably established the collaboration that resulted in this book. It is becoming increasingly clear to me that this book is actually a Mystery book. Just look at the facts alone: how numerical relationships play such a central role in the book, how precisely the words are placed in their specific locations, and how the order of the paragraphs already speaks so much to us.

Can you give an example?

Yes. A favorite example among many of those who study the book is what is written in the middle of the introductory chapter: “It is of the greatest importance to know that ordinary human powers of thought are refined powers of forming and growing. A spiritual element is revealed within the formation and growth forces of the human organism. This spiritual element appears again in the course of life as the spiritual force of thinking.” (p. 6) According to Rudolf Steiner, in anthroposophic medicine it is important to be aware of this dual nature of the etheric body. What makes us awake, thinking human beings are the same forces that build, regenerate, and develop our bodies. As a paediatrician, this opens up a wonderful perspective on child development for me, showing how forces within the human being transform themselves. When a growth spurt occurs, it’s mirrored in a diminished relationship with the outside world. Once the spurt is over, new ways of perceiving and new abilities in thinking begin to unfold. School readiness is particularly noticeable in these cases.

The work proceeds from an extension of medicine as it had been established in the natural sciences of the time, and Rudolf Steiner once again states the methods for this extension in the first chapter, as Imagination, Intuition, and Inspiration.

The dual nature of the etheric will be the topic of the opening lecture at the conference. How important is this idea?

It’s crucial for medicine. Anyone who has ever digested potatoes knows that they change the way you think. And there is a pathological dimension to it. Thinking and living are like two sides of the same coin. This becomes apparent in extreme cases when we struggle to think clearly while ill or in pain. Ultimately, healing is about the harmonious relationship between the four members of our existence: the physical, etheric, and astral bodies, and the ‘I’. The etheric body is the mediator of regulation. We must find healing from this activity. These are the forces that close a wound and that we can make available to the spiritual realm once we’ve freed them from the corporeal realm.

Steiner writes that healing must consist of treating the etheric organism.

Yes, that is what it says at the end of the second chapter, which is entitled “Why Do People Fall Ill?” Here, he further develops the special concept of the etheric body and emphasizes its significance for medicine. When we look at other forms of medicine, they often deal with the lock-and-key principle, with mechanisms of action that are scientifically comprehensible but static. Processes and living things are not fully understood scientifically, and how healing actually occurs is even less understood. That is why this description of the etheric is such a key for us in anthroposophic medicine. The only way to really access this book is to systematically go through these different elements and members of our constitution. It is worth reading the chapters at least four times to understand them: once purely factually, physically. Then, etherically, that is, by following the flow of thought. Next, we look at the composition, which brings us to the astral level. What differentiations, what structure is there, and where is each sentence located? Where is the emphasis? Where has Rudolf Steiner inserted paragraphs? This is always an indication. This astral figure is particularly beautiful! And finally, the question arises: What is the actual meaning? What is the central message or core statement in each chapter?

This is reminiscent of the threefold meaning of scripture in scholasticism: the factual meaning, the imaginative meaning, and the moral meaning. Are there further levels?

At the very least, the moral meaning is examined, felt, and scrutinized at least twice. In international medical training, following the approach outlined by Michaela Glöckler, we read the chapters five or six times, depending on the length of the working week. One aid to understanding is to “sleep on it.” We choose one viewpoint—we take it through the night with us—then, we choose another. New viewpoints emerge overnight. When we then come together for a final round, the messages from each individual are brought together to form a magnificent image. These are really illuminating experiences.

Is the book itself a medicine?

There is definitely something organizing and invigoratingly organismic in it. Each chapter can be understood as an organ, and the entire book as an organism. The special order also applies to the sequence of chapters: at the beginning, there is a comprehensive introduction, followed by a description of health, a description of illness, and a description of therapy. “Characteristic illnesses” and “Typical Medicines” are the last two chapters and the only ones in Ita Wegman’s handwriting in the manuscript. This is an example of a kind of concentration and transition to practice. It deals with characteristic clinical pictures such as hay fever and typical remedies. Rudolf Steiner aimed to describe this system of medicine in its fundamental terms and then to translate it into practice.

The title Grundlegendes für eine Erweiterung der Heilkunst [Fundamentals for an expansion of the art of healing] sounds a bit unwieldy.

The title doesn’t come from Rudolf Steiner but probably from Hilma Walter. She was a doctor who worked alongside Ita Wegman. I could imagine that Rudolf Steiner would have named the book after the first chapter: Wahre Menschenwesen-Erkenntnis als Grundlage medizinischer Kunst [True knowledge of the human being as a basis for the art of medicine]. It’s interesting to note that he was still refining the book in the very last days of his life. The chapter on knowledge of the human being was first called “Wahre Menschenerkenntnis als Grundlage medizinischer Kunst” [True knowledge of the human as a basis of the art of medicine], and then Rudolf Steiner added “wesen” [being—as in the essential nature of something] in handwriting and corrected it to “Wahre Menschenwesenerkenntnis” [True knowledge of the human being]. This is an example of how he thought through and felt his way into the smallest details of what he wanted to convey to us here. And “knowledge of human beings” is something different from “knowledge of the human.” Now, however, the book is called Fundamentals for an Extension of the Art of Healing, and this title is also beautiful and appropriate for what we have to do.

I was struck when reading it by the fact that the word “love” does not appear once in the entire book, even though it’s the golden foundation of anthroposophic medicine.

I find that very interesting because love is essential to anthroposophic medicine in the sense of warmth. Warmth (warmth ether) is what heals, and when you work with the book, you develop a great deal of warmth, that is, “love.” Perhaps that’s the answer to the question: in the book, Rudolf Steiner does not speak of love; he creates it—it’s the fruit.

You are celebrating one hundred years of working with the book. What have these one hundred years done in terms of the book itself?

In the twentieth century, we’ve of course made enormous scientific advances in medicine. That’s why I’d like us to examine each chapter in light of the current state of research in both the natural sciences and the broader scientific community—where the natural sciences today encounter the frontier sciences (including phenomena such as terminal lucidity and quantum physics). This has already been done in part, and I have not found any real contradictions with the contents of the book. Certainly, today, we would sometimes simply change the form of conceptualization. With this in mind, Michaela Glöckler has just worked through the entire book for the Rudolf Steiner Critical Edition. In its basic principles, the book has lost none of its relevance and urgency. In my opinion, this is because it deals with an extension of existing medicine that is still missing, with the role of the living, the etheric, and Inspiration and Intuition in medicine. To me, there is nothing in it that I would consider outdated. For example, in the chapter on gout, Rudolf Steiner writes about how the astral body works too deeply into the organic. Instead of uric acid being optimally excreted by the kidneys through the work of the astral body, the astral body becomes too self-centered in the lower human being, in the area of the bones, and the excretions occur inwardly in the joints. What is this image of the astral, our soul organization, working too self-centeredly and not giving anything away?

That sounds a lot like today’s society.

What sounds familiar is that there are processes that we humans actually have that connect our psyche and our body. What does psychosomatic really mean? What do we know about it today? Animals have an enzyme that breaks down uric acid and excretes it entirely differently. That means this is a specifically human problem. So, I looked at the psychosomatic research on gout. I only found something from 1988: Robert Klussmann on gout and psychosomatics.1 He finds increased self-centeredness, a narcissistic tendency—an excess of self-centered astrality—in patients with gout. Of course, there is also a genetic factor, in that gout is a predisposition. When Steiner presents such theories about the relationship between the upper and lower parts of the human being, it would be exciting to explore the current research in the respective field of a disease or healing method. And there is a lot.

Are such anthropological diagnoses also therapeutically effective?

Absolutely, that’s the beauty of it! Rudolf Steiner and Ita Wegman also named an abundance of remedies: Formica, Thuja, etc. For the treatment of hay fever, they mention Gencydo in their book, a preparation made from citrus fruits and quince. Where we search for remedies, we look at the disease processes in such a way that they are actually processes of the natural world that continue on into human beings. We take the corresponding remedies from nature, process them using pharmacologically appropriate methods, and observe how this encounter restores balance to the organism, allowing the right force to unfold.

Rudolf Steiner planned a second volume about therapy with metals. What is the status of that work?

In her preface and afterword, Ita Wegman wrote about a sequel:

“It had been our plan in a sequel to deal with the topic of the earthly and cosmic forces at work in the metals gold, silver, lead, iron, copper, mercury, and tin, and to provide a statement on how these forces can be used in the art of healing. It was also to be shown how the ancient Mysteries had a deep understanding of the relationships between metals and the planets and their relationships to the various organs of the human organism. The intention was to discuss this knowledge and to reestablish it. My work will now be to publish the second part of the book in the near future, based on the information and notes given to me.”

Considering how it’s laid out in the “Young Physicians Course” and continued in the “Pastoral Medicine Course,” I believe we can look more closely at the spiritual side of the development of the patient and the physician. I can imagine that there’s still much that could have been deepened and expanded, and this is now up to us.

Where is Rudolf Steiner’s work still misunderstood?

For me, the book is still inexhaustible. There are still centuries of work to be done, for example, to bring our conceptions and knowledge of blood and nerves into line with what is written there. There are colleagues who have done great work, delving deeper and developing ideas, such as Friedrich Edelhäuser on the question of motor and sensory nerves. Great strides have been made toward a deeper understanding of the heart as a sensory organ. Nevertheless, the question remains as to whether we have gained a sufficiently clear image. A future task is also to develop the higher sensory organs for Imagination, Inspiration, and Intuition called for in the first chapter, to read the book from this higher level of understanding, and to further develop medicine from these levels. For now, we’re still working at the level of proving what is written through the scientific and, initially, psychosomatic research results available to us today.

Where have you found your trust in the book?

I experience the work as the spiritual ground upon which we stand. And I see that it offers everyone who wants to enter anthroposophic medicine a foundation from which they can take steps beyond the uncertainties caused by all the boundary issues in medicine today. Where it becomes morally and ethically difficult, but also where we ask the big questions: Who is actually undergoing healing here? Where do you come from, newborn? Where are you going, dying person? The book is like a foundation, and one should not leave that foundation.

Compared to Occult Physiology and the “Pastoral Medicine Course,” the book strikes me as simple to read. Does that put it on the same level as an initiation book?

Here I can bridge back to the beginning of our conversation: numbers are also something simple and clear. And yet they harbor deep secrets. That is why, wherever inner secrets are mentioned, there are numerical peculiarities. The book is full of them. Cosmic realities are reflected in these laws of numbers.

One of Rudolf Steiner’s first books is Theosophy. This book also seems simple, written in the style of a woodcut. Can you see a connection here?

Yes, perhaps in the sense that Steiner also develops a view of humanity, a system, in Theosophy. And here he develops the medical system. It’s like a matrix from which one can continue to explore, and we are still in the process of comprehending it. It’s from this foundation that I mentioned before that one can reach other dimensions. In this respect, I believe it is a good bridge from Theosophy to Extending Practical Medicine. It’s different in Occult Physiology. That book is not as systematic, as the contents were presented as lectures on spiritual science. You can meditate on almost every sentence, but you can also lose your footing. Here, in Extending Practical Medicine, we’re given a foundation.

Is there something that especially inspires you?

As a pediatrician, I’m especially drawn to the idea of the dual nature of the etheric, that the same force that shapes us physically and allows us to grow is the force with which we think and spiritually explore the world.

Book Rudolf Steiner and Ita Wegman, Extending Practical Medicine: Fundamental Principles Based on the Science of the Spirit, translated by Anna R. Meuss (London: Rudolf Steiner Press, 1997).

Conference The 2025 International Annual Conference of the Medical Section. Extending the Art of Healing: Etheric Forces as Forces for the Future. September 9–14, 2025, at the Goetheanum in Dornach.

Translation Joshua Kelberman

Illustration Fabian Roschka

Footnotes

- R. Klussmann, “Der Gichtpatient im Rahmen psychosomatischer Forschung” [The gout patient in the framework of psychosomatic research] in Stoffwechsel: Der Kranke mit Adipositas, Anorexia nervosa, Bulimie, Diabetes mellitus, Gicht [Metabolism: Patients with obesity, anorexia nervosa, bulimia, diabetes mellitus, gout], edited by Rudolf Klussmann (Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag, 1988), 62–74.