How do we work with the life processes in everyday life? Can our farms be schools or even universities, or healing places for stressed and ill people? A conversation with farmers, educators, and a doctor, moderated by Ueli Hurter, at the Agriculture Conference in Dornach.

Ueli Hurter We would like to look at our farms in a new way. On one hand, farms can be places of vibrant life but a bit chaotic. On the other hand, perhaps not our farms, but many farms these days are just a garage for tractors. Our presenters look and farm in another way. We can listen to their approaches and initiatives and, hopefully, create together a vision of how our farms might look in the future.

Tobias Hartkemeyer I grew up on a farm. I loved it. I was also interested in education. So I studied both. My father died some years ago. Like me, he was a farmer and into academics. When asked what he thought about combining community-supported agriculture, biodynamics, and schools, he said, “Well, it’s impossible, but it has to be done.”

What do we need to come into life? We need places where we notice that we are needed, that it doesn’t work without us. If there’s a school where everything is ready—it’s clean, it’s already built—we ask, “What now?” There is nothing to do except a curriculum. Steiner said, when you stretch out your hand to do something meaningful, you connect rightly to the spirit world. And meaningful, he says, is something that is required by the environment. When I walk around my farm, I see something calling me to be done everywhere. But this doesn’t happen in a school. Children want to be needed. So the point of having a school on a farm is to connect to the everyday needs of the community, the earth, and life.

Can we open our minds, hearts, and will to do this? A friend of mine travels around to support these tiny farming initiatives—it’s so important to know you are not alone with this crazy idea. We met on our farm in the summer, so of course, the gardeners had to work. That did not seem right—we wanted to work together. But the gardeners said, “If 120 people come to plant lettuce with us, there will be a mess, and everything will be destroyed. Please have your talks, but don’t help us.” We thought, no, we’re going to do it: 120 people singing together and planting lettuce. Not a single lettuce was trampled, and we were done in half an hour. It did not feel like work—it was a transformation.

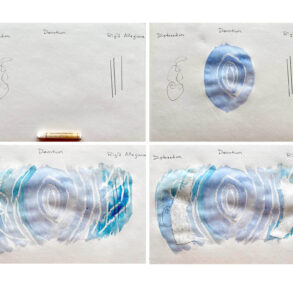

Bernie Courts I really love this conference because all of you are here, and we’re all in this together. At Ruskin Mill Trust, we’ve been developing a learning method called Practical Skills Therapeutic Education for around 30 years. All of our schools and colleges have biodynamic farms and gardens. We have researched the inner quality of the life processes so they become guiding lenses for learning. The enduring quality of breathing is rhythm. The learners experience seasonal events like lambing, calving, and the harvest in September. When the whole community celebrates a seasonal festival, each learner can reflect on where they are now compared to where they were last year. Emotional safety is in the warm welcome and an opportunity to leave stress at the gate and enter a world where warmth promotes growth in plants, relationships, and skills to relate to the world. Before they’ve even eaten the nutrient-dense produce that they helped grow, learners are nourished by a sensorially dense environment of health, beauty, and well-being. But the learner has taken a lot in. To avoid overwhelm or indigestion, they need to discern what serves them and what to let go of or excrete. They develop inner and outer trust. Maintaining requires all the life processes to be reliable and working together. It’s not until we experience reliability in our world that we can take the next steps in personal growth. The farm models constancy through the need for continuous maintenance. Finally, the quality of reproducing is regeneration. The farm offers fleece from sheep who ate from the land and colors from plants that grew in the soil and sunlight. And the learner becomes a self-generated, conscious contributor to the community.

Antoinette Simonart Ruben and I work on a biodynamic farm in Belgium with our colleagues. Step by step, we are taking over from Antoine and Leen, who started the farm. We try to do it in our own way and also carry on their spirit of respect for the soil, the living beings, and the communities of people in and around the farm. It’s a privilege because every day, I witness life finding its way. I meet the cows and they ask me gently for fresh hay. The land asks me to help it breathe because there’s too much water. What I understand from these life processes is that they are only possible in interaction with the surroundings and other living beings. Something new emerges every time we connect, or reach out, or eat. That gives me a lot of hope and energy to carry on.

Ruben Segers I tried to understand the seven life processes as a farmer—I linked them to the four seasons. The first life processes are like winter, nurturing—I digest what came to me during the year. In spring, things work in me but a bit unconsciously. In summer, the sun, the work, and the rhythm of the seasonal drum are so high and fast that I can only be doing and moving. When autumn arrives, I am struck that this beautiful summer is over. Then I realize the transformation that happened on the farm, in myself, and to the people around me. Winter comes again to slow down, let new things come, make plans, and prepare. A year is a journey to unknown places on the rhythm of the seasons.

We sometimes get city people on the farm. Every year now, there’s a bank coming to us. It’s one where you can only be a client if you have over €100,000 to invest—not for us! But they’re always so happy to be in the mud and do silly jobs that we give them. They love these things. They miss the feeling, I think, of doing something and seeing results. If you’re in a bank, you see a lot of numbers, but there’s no physical result. Then we feed them—they pay a lot for their lunch—and they go back to Brussels with a good feeling. I think that’s a good way to connect to these special people.

Looking back at 100 years of biodynamics, we can’t say that we have achieved a very high percentage of world food production. We are small but beautiful in producing food. We are big and bold in asking questions. By being honest, we can truly be open to encounters with others. Conventional, organic, biodynamic—we are all farmers. We have to be honest and say, for example, that a minimum wage is not enough. We deserve normal incomes, not to struggle to live year after year. With honesty in our stories and the seven life processes as a tool, we can be like the preparations, having a small but meaningful impact on our surroundings, our communities, and our society. Because we can never do this alone.

Martin Günther Sterner I’m a doctor. Personally, I’m still trying to get a hold of the life processes. I met them as a methodological concept in anthroposophic medicine. Well, this method made my thinking sweat! I tried to understand what Rudolf Steiner said: Life can only be here on Earth with the help of the planets. We know the zodiac as a boundary of the spiritual divine world, where the etheric forces have their home. They cross this boundary, radiating toward the center of the earth. The so-called centric earthly forces, on the other hand, radiate out from the center of the earth. Shockingly, these dear, beloved etheric forces would tear the Earth apart, and life couldn’t appear. So Steiner describes the effect of the moving planets, taking up this radiation and that radiation, bringing them together in a vortex. Working together and bringing something about in a sevenfold way, so a Venus-imprinted plant or a Saturn plant shows up. Then, I understood that the sevenfold planetary world is of utmost significance for the presence of life on Earth.

Then came a moment when I said to myself, “Uh oh, either Rudolf Steiner is wrong, or you didn’t understand anything.” I was explaining, in a lecture, how wonderfully the kidney eliminates liquid. Steiner relates the life process of maintaining to the kidneys, Venus, and copper. I asked, what does excreting water have to do with maintaining? I felt ashamed that I had followed his words without understanding them. The kidney excretes only 1% (about 1.7 litres) of the liquid that it filters—its main work is to reabsorb 99%. In this movement, it is checking and balancing the inner quality. So maybe it is maintaining in a loving way, like Venus, like copper in nature. Then I was convinced: Rudolf Steiner is really a genius. So in my work, each illness may be asked: which life process is dysfunctional here?

Ueli Hurter You said, “It’s impossible, but it has to be done.” How do you all tackle this?

BC I think Tobias hit the point when he said, “You work as a farmer, but you find yourself actually doing education, and then you have to ask what you’re educating in the human beings that stand before you.” You’re educating their emotional life and ability to build resilience so that they can step into the world and have reasonably normal relationships. In Ruskin Mill, there’s such a range of learners that we work with, from small children who don’t even know that they’re in the world to young adults who have emotional and behavioral difficulties and need something very willful to do. Within that, you’ve got this picture of creating healthy relationships and healthy people, educating their soul capacities, and then contributing to the farm and the community. We call it the Kolisko principle because Eugene Kolisko said that every farm should have a school—it would be healthy.

TH I was at Agritechnica. There was this big robot machine working without humans. Next to it was a PlayStation where you could play Farm Simulator. So who can open up the world to life? We need places where meaningful, senseful work has to be done. This is a farm. It needs culture, attention, and love. If we think about the next 100 years, let’s totally reinvent farming so that it can become this universitas. This is the place where culture happens. I invite you all: let’s go there!

MGS I implore all of us to open farms for being schools and also for being therapeutic places. Ueli mentioned what today’s farms can look like: a box with machines. Do clinics look any different? It is a pain in all our hearts to work in such places. But imagine offering doctors and therapists the possibility to send their patients to your farm to re-establish their will.

RS Flanders looks like a really big agricultural-industrial fabric. How do you do biodynamic farming in that system? We have done it, and we have tried it in several ways in Flanders. How to buy the land? We did it. How to raise so much money to buy buildings? We did it. Because we had to. Necessity gave us the will or the courage to ask our customers and our community to help us. I think impossibility is always about asking the right questions.

AS So Ruben is the positive one. I have many doubts. A lot of people around me are sick. A lot of teachers quit in Belgium because it’s becoming so difficult. I see the beginning of climate change, while others have 20 or 30 years of climate change problems. Sometimes it’s difficult to get out of bed and to say today, again, the crops, the work. But then I see my colleagues and they are very funny. Then we drink coffee together. Then, we go on the field, and we see that even in difficult circumstances, nature always finds its way. That is what really gives me hope. You can trust life again.

These are edited excerpts from a panel conversation held at the Agriculture Conference in Dornach, 2025. The entire conversation will be available on Goetheanum TV.

Panelists were: Tobias Hartkemeyer, farmer, teacher, and co-founder of the CSA farm Pente; Berni Courts, senior researcher at the Ruskin Mill Trust; Ruben Segers and Antoinette Simonart, who run the biodynamic farm De Kollebloem in Belgium; and Dr. Martin-Günther Sterner, specialist in internal medicine and gastroenterology.

More Agriculture Section at the Goetheanum

Image (from left to right) Bernie Courts, Antoinette Simonart and Ruben Segers, Tobias Hartkemeyer. Photos: Xue Li