Goethe maintained a lifelong interest in foreign cultures, particularly in their literature. He engaged deeply with the “oriental,” Indian, Chinese, and ancient Iranian or Persian-Islamic cultures.

One of the fundamental characteristics of Goethe’s work is that he is able to establish a fruitful and, in this sense, “true” relationship with his literary and scientific predecessors and contemporaries, primarily through his own productivity but sometimes even by means of the greatest opposition (as in the case of Carl von Linné or Isaac Newton). Goethe often creatively reworked the intellectual fruits of his discussions and readings into his own poetry. A well-known example of this can be found in his early work: during his time in Strasbourg in 1770/71, Goethe, inspired by Johann Gottfried Herder, read Homer and Shakespeare as well as the epic poems of the mythical, ancient Gaelic poet Ossian, written by the Scottish poet James Macpherson (1736-1796).

For the main character of Goethe’s epistolary novel The Sorrows of Young Werther (1774), the moods of Homeric and Ossianic poetry become a mirror image of his own emotional world. Indian literature also inspired Goethe to create his own works. His ballad “The God and the Bayadere” (1797) and Goethe’s lasting enthusiasm for the subtly dramatic, nature-inspired poem “Shakuntala” by the classical Sanskrit poet Kalidasa (written between 200 and 600 AD) may be mentioned here. Translations from Serbian, Slovak, and Modern Greek can be found in Goethe’s journal Über Kunst und Altertum [On Art and Antiquity] (published between 1816 and 1832). Chinese poetry inspired Goethe to write his poetic cycle Chinesisch-deutsche Tages- und Jahreszeiten [Chinese-German Book of Seasons and Hours] (1827), which includes the well-known poem “Dämmrung senkte sich von oben” [Dusk descending from on high].

The Persian Divan

But it is Persian literature that holds the greatest fascination for Goethe, and one that proves most powerful. So, from 1814, he immersed himself in the work of the Persian poet and mystic Shams al-Din Muhammad Hafiz (also known just as Hafiz or Hafez), born c. 715/1315 in Shiraz, Iran, where he also died in 792/1390.1

The translation by the Austrian orientalist Joseph von Hammer-Purgstall (1774–1856) from 1812/13, which Goethe received as a gift from his publisher Friedrich Cotta, inspired him to read it. The full title of the German edition is Der Diwan des Mohammed Schemsed-din Hafis. Aus dem Persischen zum ersten Mal ganz übersetzt von Joseph v. Hammer [The Divan of Mohammed Shemsed-din Hafiz. Translated from the Persian for the first time in its entirety by Joseph v. Hammer.]

In addition to his poetic interests, Goethe intensively and in detail researched ancient Iranian and Persian history, religion, and culture. Hafiz, whose name in the Islamic world means “he who knows the Koran,” is one of Persia’s most important and influential poets. His life coincided with the turbulent period between the Mongol invasion, Genghis Khan, and Timur, which was also an age of cultural flowering under the ruler Abu Esḥaq Inju (721-58/1321-57).

Little else is known about Hafiz’s biography, and the few references to it seem contradictory. At the same time, there is widespread agreement about him as a poet and the unrivaled significance of his work. The Iranian Iranologist Ehsan Yarshater (1920-2018) said: “In no other Persian poet can be found such a combination of fertile imagination, polished diction, apt choice of words, and silken melodious expressions.” He continued: “These are all wedded to a broad humanity, philosophical musings, moral precepts, and reflections about the unfathomable nature of destiny, the transience of life, and the wisdom of making the most of the moment—all expressed with a lyrical exuberance that lifts his poetry above all other Persian lyrics.”2 Against the background of this exuberant judgment, it is obvious that Goethe believes he recognizes a kindred spirit in Hafiz’s groundbreaking marriage of form and content.

West-Eastern Divan

Starting in 1814, his studies of Hafiz inspired Goethe to write his own extensive cycle of poems entitled West-Eastern Divan. The work can be read as a gesture of veneration for the Persian poet. The collection of poetry was written between 1814 and 1819 and first published in 1819. Goethe’s Divan, in its first edition, contains 196 poems as well as extensive prose notes for a “better understanding” of the work (“Notes and Essays for a Better Understanding of the West-Eastern Divan”). Goethe writes these notes between 1816/17 and 1819. In the final version of 1827, the West-Eastern Divan was expanded to include another 43 poems and now contains a total of 239 poems. Biographically, the creation of the work is inextricably linked to a new love interest in Goethe’s life: in 1814, during a journey to his hometown of Frankfurt am Main, which he had last visited in 1797, the poet met the actress Marianne Jung (later von Willemer), who was 36 years his junior. In 1815, he traveled from Weimar to the Main for a second time. This visit leads to a further deepening of the relationship. His correspondence with Marianne von Willemer inspires Goethe to write a large number of poems. He also includes several poems by Marianne von Willemer herself in the West-Eastern Divan, which is probably unique with regard to the creation of his works, for which, according to current knowledge, no further authorship by others is attested. His affection for her is expressed directly in the poems of the eighth book of the Divan (“Book of Zuleika”).3

Cultural Approaches

Goethe was one of the first Europeans of his time to take Eastern and Oriental philosophies, philologies, and religions seriously. Thus he was an advocate for establishing philological Oriental studies in Germany, as developed by the French scholar Antoine-Isaac Silvestre de Sacy (1758–1838), thereby freeing them from the narrower orbit of theology and biblical studies. In 1817, de Sacy’s student Gottfried Kosegarten (1792–1860) was appointed to a professorship in the neighboring town of Jena. The orientalist advised Goethe, in particular in the final phase of his work on the West-Eastern Divan4 and, among other things, made numerous suggestions for corrections to the “Book of the Parsees” (as part of the West-Eastern Divan). At least indirectly, Goethe’s interest in Oriental, especially Persian, literature at the University of Jena may have led to an increasing appreciation and professionalization of this discipline.5

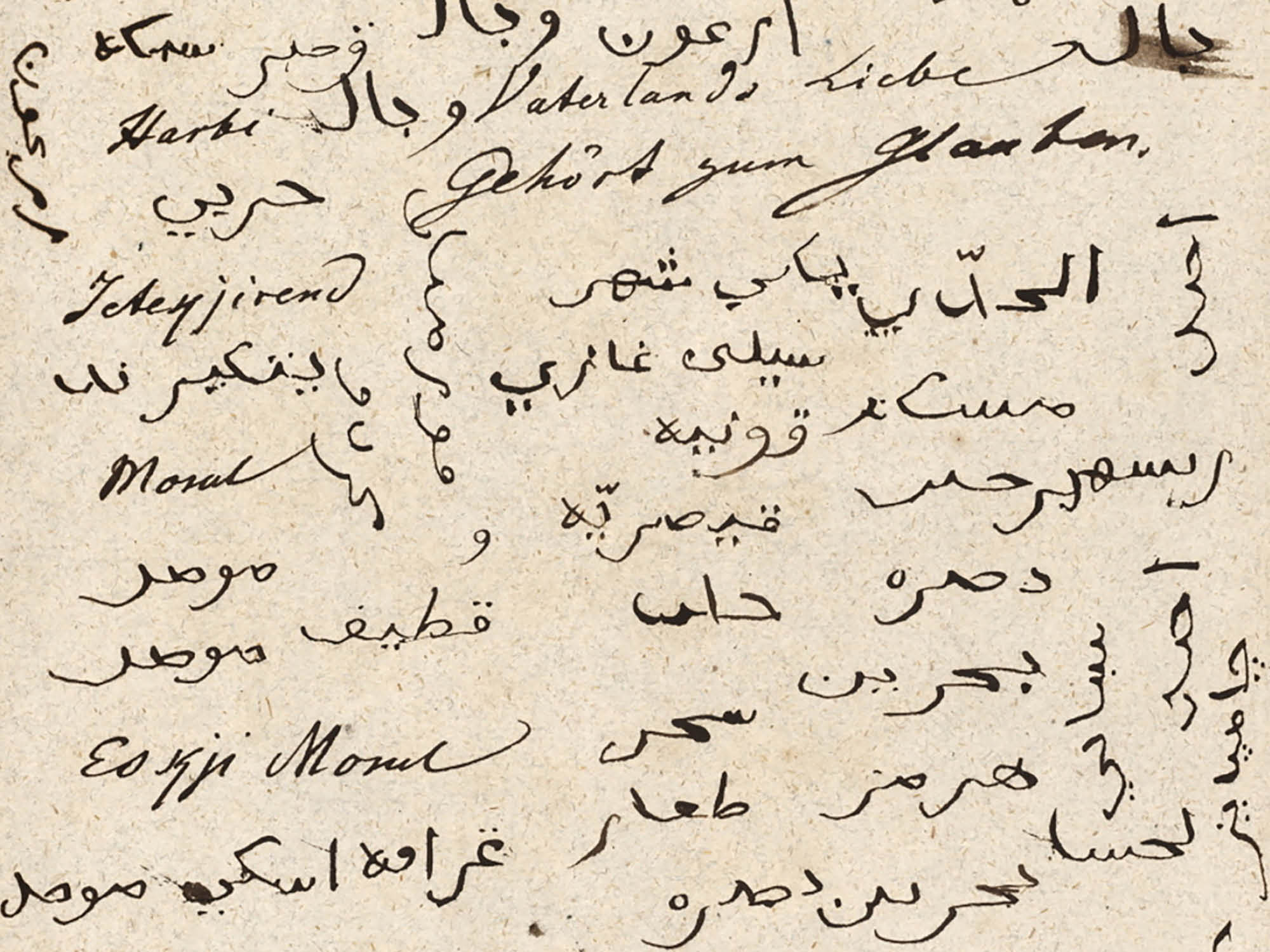

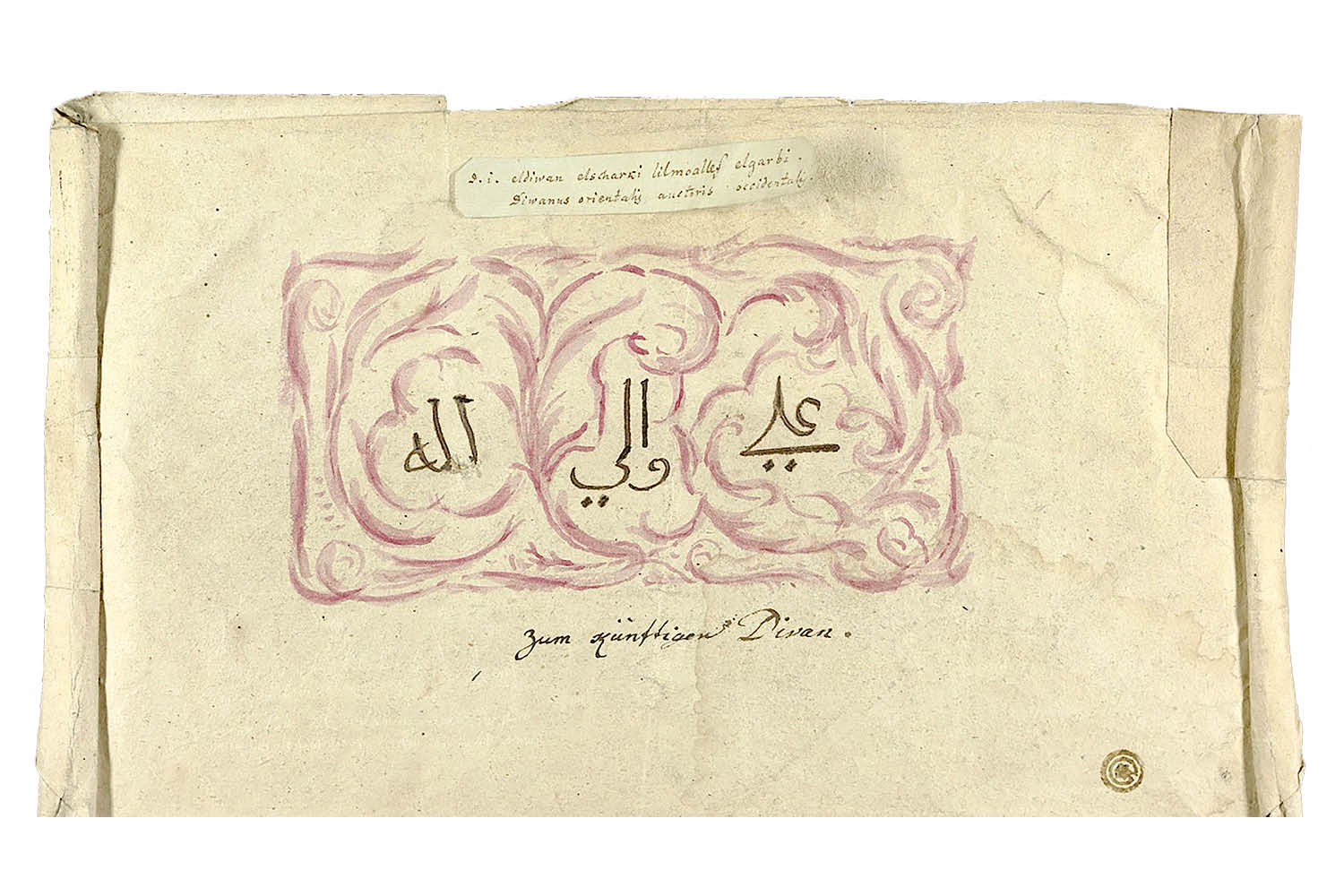

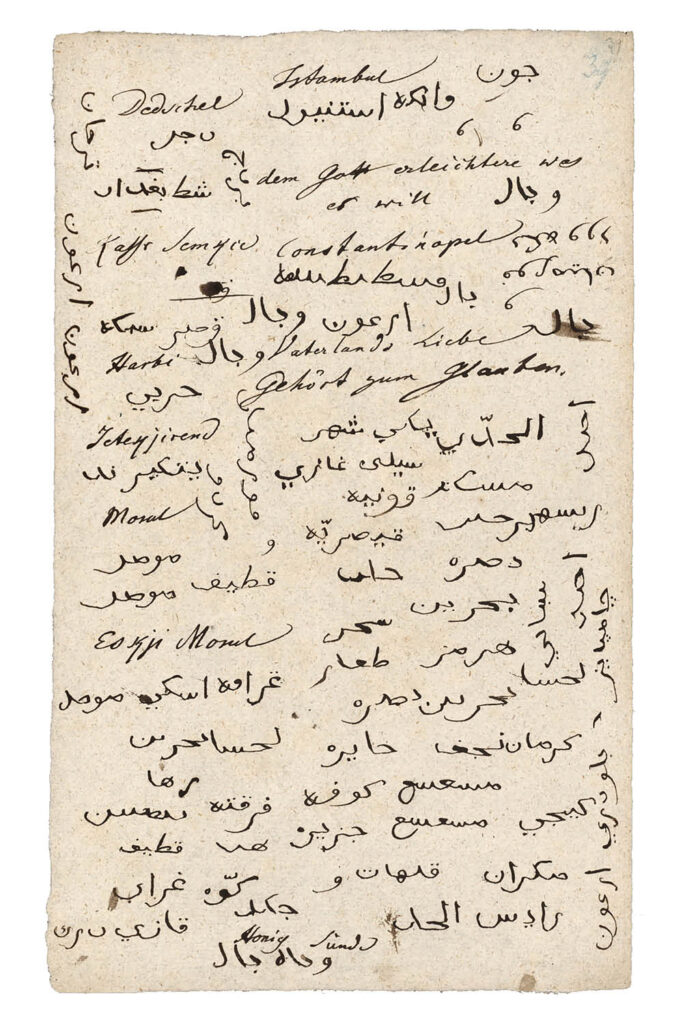

Goethe’s struggle to find a “Western” approach to “Eastern” poetry is evident, among other things, in the large number of title variations: German Divan was one of Goethe’s announcements in 1815, while West-Eastern Divan or a collection of German poems with constant reference to the Orient was the title of an advertisement in 1816. The first edition of 1819 finally bears the full title: West-Eastern Divan by Goethe, set in Gothic typeface and laced with foliage, with an Arabic secondary title on the opposite page: Ad-diwan aš-šargi li’l mu’allif al-ġarbi. In Goethe’s definitive edition, the work is, as already mentioned, only any longer titled simply as West-Eastern Divan. The term “divan,” which is commonly used in Persian and Turkish poetry, means “collection, assembly” and, in this context, refers to a collection of poems. Following Hammer-Purgstall’s translation of Hafiz, Goethe’s Divan contains twelve “Books” (in this context, a “Book” corresponds to a long poem), each of which is preceded by its own title in both German and Persian.

The first book of Goethe’s collection of poems, the Book of the Singer (“Moganni Nameh”), invokes God with the Hebrew name “Elohim” (in the poem “Creation and Animation”), while the fourth Book of Reflections (“Tefkir Nameh”) addresses God with the Arabic name “Allah” (in the poem “Ferdusi”). Thus two Abrahamic religions are united in the Divan: “God’s is the Orient!/God’s is the Occident!/Northern and southern lands/Rest with peace in his hands”6 is in this spirit the first stanza of the poem “Talismans” in the Book of the Singer. Four of the most important other subjects in the Divan are love, the craft of poetry, the poet’s relationship to the social and political world, as well as the relationship of the self to the foreign and unknown. As far as the form is concerned, Goethe makes use, among other things (but not exclusively), of the Oriental poetic form of the “ghazal” used by Hafiz,7 for example, in the poems “Imitation” (in the Book of Hafiz) and “Zuleika” (in the Book of Zuleika).

The Personal and the Transcendental

Above all, Goethe evokes the mystical content of his Persian model, so that it pervades the entire cycle as a theme and mood.8 Thus the love poems in both Hafiz’s and Goethe’s Divan are to be read as a metaphor for the spiritual aspirations of the seeker, for the human being’s striving for unity with the divine. In Goethe’s and Hafiz’s poetic words, earthly and heavenly love, the personal and the transcendental meet in equal measure. The well-known poem “Blessed Longing” in the Book of the Singer, written on July 31, 1814, in the first year of his work, is a prime example of this. The term “blessed” points to union with the divine but also to the yearning with which human beings move towards their origin. In “Blessed Longing”, the mystical path of self-conquest is praised, as well as the death of the lower self for the sake of higher development and perfection. Thus the last verse reads:

And as long as you don’t have

This: dying and becoming

You are but a sorry guest

On the dark earth roaming.9

Another mystical leitmotif of the Divan is the idea of a tiered realm of love, which finds its poetic expression in the closing verses of the poem “Higher and Highest” (in the Book of Paradise):

And now I pass in every place

More easily through the eternal circles,

Which are imbued with God’s own word

In ways that are both pure and living.

Unrestrained with ardent vigour

Ending does there none appear

Till in view of love eternal

We soar away and disappear.10

Despite extensive parallels to Hafiz, Goethe’s poetic approach to the Persian poet is not a simple imitation, in the traditional sense of the word. Goethe’s confidant Johann Peter Eckermann (1792 –1854) made the following far-sighted observation about the relationship between Goethe’s and Hafiz’s sources of inspiration: “The first and most original thing in a poem, the enlivening and inspiring point from which everything emanates, is the spirit underlying the whole. This spirit is superior to all imitation, for it arises from the subjective self of the poet.”11 Instead of speaking of imitation, it would therefore be truer and more appropriate to speak of a poetry that is of “the same spiritual origin,” which Goethe is inspired to create independently through his contact with the poetic spirit of Hafiz. Hafiz and Goethe can thus be said to look to the same source, the same spiritual model or archetype, which produces different poetic metamorphoses in the East and the West. In this sense, there is also reference to “Emulation” [Nachbildung] as a poem in the Book of Zuleika is entitled. In this case, Hafiz provides the “spark”12 for Goethe, which continues to unfold in the mind of the German poet and “puts an end” to a “dead form”—to which mere imitation of the model would lead.13

Escape and Travel

In his “Announcement” of 1816 in the Morgenblatt für gebildete Stände [Morning paper for the educated classes], Goethe notes with regard to the opening poem “Hegira,” which was one of the last poems to be written in the first year of work on Christmas Eve 1814: “The poet regards himself as a traveler. In no time at all, he has arrived in the Orient. He takes pleasure in the manners, customs, objects, religious beliefs, and opinions; indeed, he does not reject the notion that he himself is a Mussulman.”14 “But most of all, the author of the preceding poems wishes to be regarded as a traveller”, and equally as a “trader” who “obligingly” lays out the treasures of his journey for “his nearest and dearest”15 as it says in the “Notes and Essays” on the Divan. A “higra” (from which the title “Hegira” is derived) is not a journey in the usual sense, but migration, an escape. In Arabic, the word for this is Hijra, which originally refers to Muhammad’s migration from Mecca to Medina in the year 622, which also marks the beginning of a new era in the Islamic world.16 During his work on the Divan, Goethe speaks in a similar sense in the Tag- und Jahreshefte [Day and Year Books] of 1815 of his escape “from the real world, an open and covert threat to itself, into the imaginary world.”17 The first verse of the poem “Hegira” reads:

North and West and South fragmenting,

Thrones are shattering, empires trembling,

Flee you to the East untroubled

Air of patriarchs to savour,

Among loving, drinking, singing

Khidr’s spring shall bring you youth.18

The verses with which Goethe takes up the trochaic tetrameter of Purgstall-Hammer’s Hafiz translation can be understood, on the one hand, as an allusion to the political situation of the Coalition Wars, which saw the end of the Holy Roman Empire in 1806 and the Wars of Liberation. The motto that prefaces the first book of the Divan, which covers the period between Goethe’s departure for Italy in 1786 and 1806, supports this interpretation:

Twenty years—I let them pass

And enjoyed what I was given;

In a series full of beauty

Like in Barmecidean times.19

Nevertheless, it would be too superficial to attribute Goethe’s journey or escape to the Orient only to the political circumstances. Rather, in my opinion, the political situation in his western homeland enables him to move to the (imaginary) land of the East by means of the poetic imagination and thus to rejuvenate himself at “Khidr’s spring”.20

Real World

It has become clear how this poetic work plays a special role in Goethe’s imaginative journey. Thus, the first book of the Divan, the Book of the Singer (Persian: “Moganni Nameh”), is primarily concerned with questions of the poet and his craft. Goethe’s poetic journey to the Orient is not fictional in the conventional sense of the word. It is not merely invented. On the contrary: Goethe is convinced that a world with its own reality corresponds to the poet’s imagination. In his poem “Song and Creation” in the “Book of the Singer,” he uses an analogy: just as the sculptor works their clay into concrete forms, the poet scoops real forms, different but equal, out of the element of water. In the second and third verses of “Song and Creation,” the lyrical “I” speaks as the poet with images that belong to the element of water about the poet and his work: “But it is with great delight/We reach into the Euphrates,” and it continues: “When the poet’s pure hand scoops/Conglomerating water.”21

Goethe introduces the prose part of his work, which is intended to provide a better understanding of the collection of poems, with the lines that include the following: “If the poet you wish to know,/To his country you must go.”22 In this case, the poet’s country is the realm of the imagination. It is not the imagined geographical place that is entered with poetic imagination, but the spiritual place, so that in the case of Goethe’s West-Eastern Divan, we can certainly speak of a spiritual geography. Goethe was inspired by Hafiz to go there. The Divan can, therefore, rightly be called a “voyage spirituelle.“23

Imagination as a Cognitive Tool

The imagination plays an important role not only in Goethe’s poetry but also in his science. Without a noetic faculty that breaks through the sensory world into a spiritual-imaginative realm (without becoming abstract in the process,) Goethe would not have been able to perceive the archetypes (such as the archetypal plant and the archetypal phenomena in the theory of colors.) Imagination as a cognitive tool plays a similarly important role within the mystical currents of Islam as it did for Goethe. The French philosopher and scholar of Islam, Henry Corbin (1903–1978), known for his studies on Islamic mysticism, Persian philosophy, and the German intellectual tradition, including phenomenology and existentialism, also refers to Goethe in numerous places in his work for this reason. There is, among other things, an extensive treatment of Goethe’s fragmentary poem “The Mysteries” in Corbin’s Histoire de la philosophie islamique, 1964 [History of Islamic Philosophy].24

In his work L’Imagination créatrice dans le soufisme d’Ibn’Arabi (1958; republished in English in 1998 with the title Alone with the Alone),25 Corbin, starting from the spiritual world of Sufism and the teachings of the Sufi master Ibn Arabi (1165–1240), considers the idea of a productive imagination (imagination créatrice) and a corresponding world of the imaginal: the “mundus imaginalis” (also Malakut or “world of angels”). According to Corbin, the “mundus imaginalis” forms a kind of middle realm between the physical-sensory and the purely spiritual world in Islamic mysticism. According to Corbin, Islamic mystics (also Gnostics) access the events that take place on the plane of the “mundus imaginalis” through an imaginative consciousness to which a noetic or cognitive value can be ascribed. The “mundus imaginalis” is no more a fictitious world than Goethe’s poetic imagination of the East, but rather a reality of its own, in Corbin’s words, an “imaginatio vera.“

It is not surprising, therefore, that Corbin also refers to Goethe’s Theory of Colours in several places in his work. For example, in his discussion of the spiritual physiology of colors in L’homme de lumière dans le soufisme iranien (1971) and in his essay “Realism and Symbolism of Color in Shiite Cosmology” (in Temple et Contemplation, 1986). In this context, Corbin draws an analogy between Goethe’s physiological colors, as he introduces them in his Theory of Colours, and the soul-spiritual experiences of light and color by the Islamic mystic (“l’homme de lumière“) during his spiritual ascent. As for Goethe, the act of imagining also serves for the Sufi as a precise hermeneutic faculty of epistemological value, according to Corbin. Fully developed organs of the imagination serve as “mirrors” (Corbin) or, as it says in the second part of Goethe’s Faust, as a “reflection” of the archetypes. What these light organs “reflect” are existing realities but not necessarily already manifested ones. Corbin also refers to these realities (using C.G. Jung’s term) as archetypes or archetypal images. According to Corbin, all phenomena of our earthly world, including that of color, can be explained by their origin in archetypes from higher worlds. Corbin agrees with Goethe’s view that all types of basic or archetypal phenomena, including mystical ones, are as irreducible as perceptions of sound or color. The ontology and cosmology of Sufism, Corbin says, is based on the firm conviction that the described intermediate world of the “mundus imaginalis” exists. Its existence guarantees the validity, as it were, of their mystical experiences.

The Age of World Literature

Eckermann noted the following about a conversation with Goethe on January 31, 1827: “I see more and more, Goethe continued, that poetry is a common possession of humanity, and that it emerges everywhere and at all times in hundreds and hundreds of people. One person may do it a little better than another and stay afloat a little longer than another, that’s all […] I therefore like to look around among foreign nations and advise everyone else to do the same. National literature doesn’t have much meaning now; the age of world literature is at hand, and everyone must now work to accelerate it.”26

Goethe’s idea of world literature is the fruit of his lifelong study of the arts, religions, and cultures of foreign peoples. Different works of literature are metamorphoses of the one language for Goethe, expressed in a variety of imaginative images. This “one” language only becomes visible in the diversity of its cultural forms and shapes. Thus Goethe’s formulation of world literature evidently does not imply a standard for a so-called classic, transnational literature. World literature, in his sense, aims much more at the dynamic process of intercultural dialogue and mutual enrichment among cultures. The supersensory imaginative world is reflected in world poetry in a myriad of ways. Hence universality at the intercultural level means neither the universalization of a single culture nor the blurring of differences between cultures. The unifying spirit would rather be the aesthetic value of beauty or, as Goethe admits to Eckermann in this context, the “beautiful person” as well.27

Translation Christian von Arnim

Footnotes

- On Hafiz’s life and work, see, for example, the entry “Hafez”, in: Encyclopaedia Iranica.

- Ehsan Yarshater, Hafez, in Encyclopaedia Iranica.

- This autobiographical background, kept secret by Goethe, was only uncovered by Hermann Grimm in 1869.

- See Norbert Nebes, “Orientalistik im Aufbruch. Die Wissenschaft vom Vorderen Orient in Jena zur Goethezeit” [Oriental Studies on the Rise: The Academic Study of the Middle East in Jena in Goethe’s Time], in: Goethes Morgenlandfahrten. West-östliche Begegnungen [Goethe’s Voyages to the East. West-Eastern Encounters], edited by Jochen Golz, (Frankfurt a. M. 1999), p. 66-96 5 See ibid.

- Johann Wolfgang Goethe: Sämtliche Werke nach Epochen seines Schaffens (Münchner Ausgabe) [Complete works by periods of his work (Munich edition)] , Volume 11.1.2: West-östlicher Divan [West-Eastern Divan], edited by Karl Richter in collaboration with Katharina Mommsen and Peter Ludwig, (Munich 1998), p. 15. (Hereinafter I will quote from this volume with the abbreviation MA 11.1.2 and the page number.) English translation of the poems by Christian von Arnim.

- Ibid.

- MA 11.1.2:46.

- MA 11.1.2:12.

- It is an Arabic form of poetry with couplets and mostly a uniform meter and rhyme.

- MA 11.1.2:124.

- See Walter Veit, “Goethe’s Fantasies about the Orient” in Eighteenth-Century Life 2002, Vol. 6 (3), Fall 2002, p. 164-180, here p. 169.

- MA 11.1.2:21.

- MA 11.1.2:124.

- Johann Peter Eckermann, Beyträge zur Poesie mit besonderer Hinweisung auf Goethe, (Stuttgart 1824), p. 135.

- MA 11.1.2:26.

- Ibid.

- MA 11.2:208.

- MA 11.1.2:130 f.

- Goethe also refers to his secret departure for Italy as “my Hegira from Carlsbad” in Italian Journey.

- MA 14:239. “Khidr” is the name of the prophetic guardian of the source of life.

- MA 14:239.

- MA 11.1.2:129.

- Walter Veit (2002), p. 168.

- MA 11.1.2:18.

- MA 11.1.2:129.

- Henry Corbin, Histoire de la philosophie islamique, Collection idées No. 38, Paris 1964.

- MA 19:207.