Jacques Lusseyran (1924–1971) has been well-known in France since 2015. His work is now considered a classic of French literature. What connects Jacques Lusseyran to anthroposophy? He only began reading anthroposophical works, mainly by Rudolf Steiner, late in his short life. However, he came into contact with the substance of anthroposophy at an early age through his father. François Lusseyran, his half-brother, writes.

First of all, I can personally testify that Jacques Lusseyran clearly realized one day that anthroposophy was his spiritual path. In the summer of 1966, when he was 42 years old and I was 12, Jacques and Marie, his last wife, were traveling through the French capital. They lived in the United States and took advantage of the summer breaks to visit our father and his new wife, my mother.

I can still see him taking my cello in his hands to relive the experiences that this instrument had brought him as a teenager. I remember the joyful intensity of the conversations between the four adults during dinner, Jacques eagerly defending his ideas while reaching for the carafe to pour himself a drink. His blindness went unnoticed in those special moments. At the end of the meal, Jacques turned to Marie and said, “Would you like to show François my Paris?” So I set off alone with Jacques and Marie in her rental car. I rejoiced in this extraordinary moment.

He knew exactly how to orient himself in Paris. I was amazed when he said to Marie: “Turn right, go up Rue St. Jacques!” At the end of our walk, we took a seat at La Maube, a bistro on Place Maubert in the neighborhood of the Sorbonne—a café he really wanted to go to because it was so full of memories for him. When we were about to leave, Jacques turned to me and, without any connection to the rest of our conversation, said: “François, now I know: anthroposophy is my spiritual path.” I was 12 years old, and it still astounds me, but I understood what he was saying. I sensed the uniqueness and significance of these words, which he seemed to have formulated in a very conscious way. They were not empty words.

The Masters

Jacques’s connection to anthroposophy and the work of Rudolf Steiner went through a clear progression, and this development seems significant to me. When we look at the chronological sequence of his life, we can say that he became acquainted with anthroposophy before he met the work of Rudolf Steiner through our father.

In his book And There Was Light, Jacques described in detail how, when he was a child, his father’s experience of anthroposophy provided him with a certainty that the world had meaning. Our father’s approach to anthroposophy was discreet—not so much ideological but more an unspoken sharing of an essential experience that the inner life of thinking, as cultivated by anthroposophy, can develop an interest in the world around us. It was a decisive example for Jacques and me.

As a young adult, Jacques began spiritual work with Georges Saint-Bonnet, a Parisian occultist whom he met in 1952 at the age of 28. He described this experience ten years later in his 1963 book Georges Saint-Bonnet, maître de joie [Georges Saint-Bonnet, master of joy]. Joy became an expression of presence within oneself. In my view, it’s not a detour, a spiritual derailment, or an incomprehensible illusion, as Jérôme Garcin understood it in his beautiful biography [of Jacques] Le voyant [The seer]. A passage in [Jacques’] book explains this point fully:

“I had not followed my father’s footsteps and joined the Anthroposophical Society. But, that didn’t actually mean anything. The seven years after the war brought with them both human and spiritual unrest for me. Besides, the reason I didn’t join (if there was any reason at all) wasn’t due to doubts about Steiner’s teachings or the man he was. Rudolf Steiner was an ‘initiate,’ I was convinced of that, in the direct and simple sense of the word, that is, a human being who saw the true order of the world and was commissioned by God to translate it for other people. It was mainly that Steiner’s earthly existence had ended, my father had also not met him personally, and I’d never be able to meet him in this world. I’d always lack some final proof or, rather, a concrete impulse.

“Inwardly, I’d recognized Rudolf Steiner as my master. But, I was too weak or too demanding (others can decide which) to be satisfied with this indirect presence. The time had come for a living master.

“Could this master be Georges Saint-Bonnet? From my very first encounters with him, I continuously asked myself this question. Indeed, if my first intuition was confirmed, he was my master. But, at the time, I wasn’t yet convinced. He could be my master, as long as his teaching didn’t contradict Rudolf Steiner’s.”1

The Anthroposophical Community

In parallel with Jacques’ experiences with Georges Saint-Bonnet, he also has a connection to the French anthroposophical community of the 1950s. In the summer of 1953, the second issue of the new anthroposophical review Triades, founded by Simonne Rihouët-Coroze, contained a long and beautiful review of Jacques’ book And There Was Light [French original: Et la lumière fut, published 1953], which begins as follows: “Jacques Lusseyran has written more than just a moving book: He offers his contemporaries a valuable document about the strength of a soul becoming conscious of powers slumbering within himself. From the very first words, he addresses his audience and offers them his treasures: ‘I will tell you the price of freedom, the kingship of the inner life, and the enlightenment of love.’ These are not words tossed out lightly, but dearly bought realities, won through such cruel testing at such a tender age that they cannot be heard without respect.” In the following Fall issue of 1953, a small article by Jacques himself was published: “Le Quatrième” [The Fourth], in which he recounts his experiences in the cell of the Fresnes prison. In the Spring 1954 issue, a longer article by Jacques was published: “La mort devient la vie” [Death becomes life].

Fifteen years later, in April 1970, Jacques held a lecture in the great hall of the Goetheanum on the topic “The Blind in Society.” The hall was full and his lecture began in an unexpected way: “I have returned because I know that this place, the Goetheanum in Dornach, is really my spiritual cradle. These forces make me more than just a body and more than just an intelligence. They were given to me by this place. I know that I received them through the teachings of Rudolf Steiner, as they were imparted to me by my father. I know that I owe it to these forces that I did not become desperate when I lost my eyesight and that I found the courage to survive when I was sentenced to death by human beings. This is thanks to Rudolf Steiner’s teachings! There are moments in life when you have to say what you know, and there are even moments when you have to publicly recount it. It is a great emotion, but above all it is a great calm, the calm of a prayer.”2

Jacques spoke these radical words fifteen months before his fatal accident. They don’t contradict the fact that the relationship between his consciousness and anthroposophy evolved. One can see a wisdom here that allowed Jacques to be a free seeker, full of talent and strength, finding a completely personal expression, such a striking style to bear witness to his spiritual experiences. This is the testimony that touches so many human beings on different continents in all the different languages into which his books have now been translated.

His explicit knowledge of Rudolf Steiner’s work can be seen in the correspondence with his father. In the last five years of her life, Marie read to Jacques from Steiner’s books aloud. Conrad Schachenmann, one of her friends, remembers Marie reading the books in German.

Both Personal and Universal

When discussing Jacques Lusseyran’s work, it is difficult to avoid the incredibly harsh circumstances of his biography: blindness and deportation. But, even if these personal events are fundamental to his life, what he accomplished through his work is more universal. He was able to convey how the act of seeing is integral to human consciousness beyond the physical sense of sight. He spoke about this in an address to a group of young people in Zurich who had come together in 1970 for a conference on social professions:

“Seeing is a fundamental act of life, an inseparable, indestructible act, regardless of the physical tools used. Seeing is a movement of life that occurs within us in front of objects and in front of any external determination. Facing the objects and going beyond them, when the material instruments of the encounter are by chance missing. Seeing occurs within you. If we were not first given the inner light and along with this all the colors, the currency of light, we would never be able to admire the colors of the world.”3

To see and experience illumination—is that not more like touching an essence than simply an object? No one has ever seen light with their eyes because even though light makes the world visible, it remains invisible to the eye, only revealing itself in its effects.

Seventeen years earlier, in And There Was Light, he wrote: “Every time we take the trouble to get to the bottom of our experience and extract from it all that it contains in terms of simplicity and hiddenness, we immediately stop talking about ourselves and only about ourselves—we enter the most valuable realm, that of universal experience, of shared experience.”

Mathematical understanding has this property—it is experienced entirely within the individual, wholly intimately, and therefore subjectively, yet everyone knows that another person following the same line of thought will arrive at the same result! This is the essence of spiritual science. It’s possible because what was established in the Renaissance as the methodological basis of modern science—separation between subject and object—has been overcome. In this sense, Jacques is a spiritual researcher, a contributor to a modern science of the spirit, to anthroposophy, which, by its very nature, must always be updated in order to continue to emerge as a societal fact. Fortunately, he’s not the only one, but he exhibits an important uniqueness that has been strangely unrecognized for a long time. In a certain way, he complements a famous predecessor of French culture, one he admired very much: Proust.

The Unfinished and the Finished

Jacques did not receive immediate recognition. Even on his return to France from Buchenwald [the concentration camp in Weimar, Germany], he was met with suspicion. How could a blind man survive these inhuman conditions without collaborating? He had to go into exile, to the United States, in order to teach because a French decree from the Vichy era prohibited blind people from teaching. We know that the leadership at the Goetheanum hesitated in allowing Jacques to give a lecture. In retrospect, it seems to have been the right decision to welcome him in 1970. What motivated the audience that filled the Great Hall?

One can also point to the difficult path of his work. Why did it take until 2008 for it to begin to shine in his own country and his own language? This beginning occurred thanks to his first wife, Jacqueline Pardon, mother of his first three children, who knew how to mobilize old comrades from the resistance after the post-war quarrels were finally buried. This certainly helped to raise his profile. But the major turning point came in 2015, with the publication of the biography Le voyant [The seer] by the talented journalist with a large French audience, Jérôme Garcin. Jacques Lusseyran’s work, which ultimately proves to be the fruit of an authentic anthroposophical path, is now an essential part of France’s literary heritage.

One question remains: if he hadn’t died before his time, what form would Jacques’ commitment have taken when he returned to old Europe and the University of Basel in Switzerland, inspired by Rudolf Steiner’s concepts, thanks to the patient work of his friend Conrad Schachenmann? The manuscript found in his suitcase, entitled Contre la pollution du moi [Against the pollution of the ‘I’], provides a testimony to this:

“The ‘I’ has its rules. Let’s choose another word: The ‘I’ has its conditions for growth. It’s nourished only upon movements that it, itself, makes. The movements that others make in its place do not help but instead make it poorer. . . . The ‘I’, if it isn’t entirely asleep, knows that a truth never consists in what most human beings do or say. It knows that a truth is what appears at the very tip of each experience, an experience that is personally and thoroughly lived.”4

Author’s note: I would like to thank Peter Selg for his impressive and valuable research published under the title Der Mut des Überlebens [The courage to survive] (Arlesheim: Ita Wegman Institute, 2024). I recommend reading this book. While reading it, I came across several passages by Jacques Lusseyran that I incorporated in this article. [Cf. “The Courage of Life: About Jacques Lusseyran (1924-1971),” Goetheanum TV.]

Translation from French to German Louis Defèche

Translation from German to English Joshua Kelberman

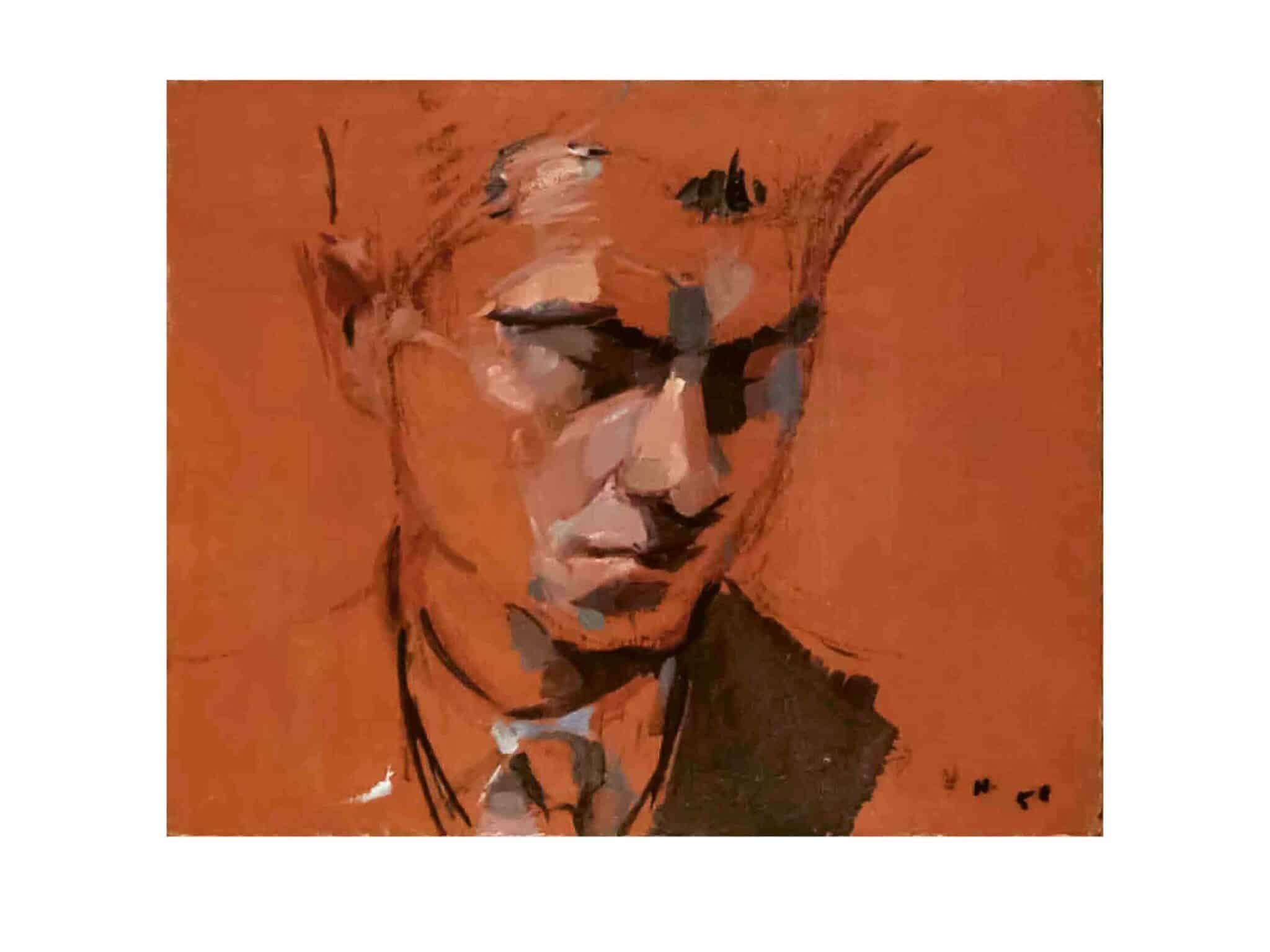

Title Image Jean Hélion, “Jacques Lusseyran,” 1958; Private collection, © 2024, ProLitteris, Zürich.

Footnotes

- Jacques Lusseyran, Georges Saint-Bonnet, Maître de joie (Millau, France: Edition A.G.I., 1964).

- Jacques Lusseyran, “Un nouveau regard sur le monde,” [A new way of looking at the world] in La lumière dans les ténèbres [Light in the darkness] (Paris: Éditions Triades, 2002); [cf. “Blindness, a New Seeing of the World,” in Against the Pollution of the I: Selected Writings of Jacques Lusseyran (New York: Parabola, 1999); Jacques Lusseyran, “L’aveugle dans la société” [The blind in society] in La lumière dans les ténèbres [Light in the darkness]; “The Blind in Society,” in Against the Pollution of the I: Selected Writings of Jacques Lusseyran.]

- Jacques Lusseyran, Le monde commence aujourd’hui [The world begins today] (Paris: Folio, 2016).

- Jacques Lusseyran, Against the Pollution of the I: Selected Writings of Jacques Lusseyran (New York: Parabola, 1999).]