The idea of reincarnation belongs to the core of anthroposophical thinking and is currently the most widespread conception of what happens after death. However, both proponents and critics of the idea have not fully grasped its character in Western culture, and misinterpretations have been used to speak out against anthroposophy. Jens Heisterkamp wrote a small book on the subject and summarized his thoughts for us here.

The religious scholar Helmut Obst once described reincarnation and karma as a “successful trans-religious idea”. Indeed, more people around the world today believe in reincarnation than in the resurrection of Christ—even in Western church circles. The concept has also long since found its way into everyday culture. Thus, for example, the words “More eco—higher karma” are emblazoned in giant letters on the recycling refuse lorries of the Stadtwerke Frankfurt municipal utilities. Although this is meant tongue-in-cheek, the fact that an advertising agency is confident that the city’s population can relate to it says a lot. And recently, in the sensitive film Past Lives, the protagonist couple saw the reason for their peculiar attraction to each other in that they had already been through many lives together. The examples are endless.

Contrary to these phenomena, reincarnation and karma have gained a bad reputation in other circles. Karma is considered irrational esotericism by some. Some critics suspect that supporters of the idea are implying that people themselves are to blame when they suffer misfortune or fall ill. In the politics of the coronavirus pandemic, progressive authors such as Pia Lamberty even labelled the idea of karma as “inhuman” (Lamberty/Nocun, Gefährlicher Glaube [Dangerous beliefs], 2022).

However, there is a need for clarification in both directions, in both the rejection of this idea and in its naïve popularisation: karma in the Western sense is not (or is no longer) the deterministically closed chain of cause and effect that was associated with it in Asia. Neither is it an all-around explanation that allows everything we encounter to be dismissed with the exclamation, “That’s just karma!”

There is little public discernment that reincarnation and destiny have taken on a different, freer character in the West. This is already evident in the first systematic appearance of this idea in Lessing at the end of the eighteenth century and in the philosopher Gideon Spicker (Lessings Weltanschauung [Lessing’s Worldview], 1883). Both were the first to place the principle of multiple earth lives in a developmental context. Immortality is no longer understood as eternal damnation or bliss after death but as development beyond one life. For both, the goal of rebirths no longer lies—as it does in the East—in the hoped-for exit from the endless “cycles of rebirth” but in a progressive maturing of personality.

The quality of individualisation applies all the more to the way in which Rudolf Steiner took up and continued this motif. It is the key to his image of the human being but also an eminent task of cognition. In the modern sense, it is not possible to “believe” in reincarnation; it is not a one-time choice of worldview. Rather, working with reincarnation and karma means embarking on a path that constantly leads to new approaches to something other par excellence, an other which does not fit in with the assumptions of the material and naturalistic worldview. More important than any possible identification of concrete previous incarnations is the complete change in the conventional understanding of reality that takes place with the turn to reincarnation and karma. If we consider reincarnation and karma to be possible, the foundations of the prevailing worldview are shaken.

Reincarnation and Karma as a Provocation

It starts with the existence of an immortal subject that reincarnates. This really seems provocative in view of the consideration that human existence is deemed to have been explained by science. If the personality is seen as a product of social imprints and brain waves, where is there room for continued life? However, the possibility that existence after death touches on something completely different is something we realise very clearly when we witness the death of a person. As soon as the last breath has passed, the radical nature of the limitations of physical life becomes apparent: there is nothing left of the soul and spirit that Aristotle described as the form that gives life to the body. Where has the person gone who was present just moments ago? On a very basic level: where are the dead? What kind of “world” do they live in? Furthermore, how exactly do they live after death, and how do they fill their existence?

No conception based on physical reality can help us here, and we would do well to dispense with any images of an afterlife and its conditions. Can we tolerate that a completely different understanding of the entire reality of this world and the world beyond is necessary in order to be able to conceive of the pre- and post-natal nature of human beings? Can we tolerate how little we know about it—despite Rudolf Steiner’s astonishing accounts?

A second provocation arises in thinking about the way in which something like karma must work in order for it to be considered a universal law of compensation. Karma not only means that there is a dimension between death and rebirth in which we, as immortal individuals, are time and again kept safe, in which we continue to develop after death, free ourselves from burdens and prepare ourselves for new tasks. This world is also permanently intertwined with earthly reality so that consequences from the past and causes for the future can be appraised. “Here” and “there”, this world and the hereafter, are by no means strictly separated, perhaps rather two sides of a more comprehensive reality.

How does it happen, for example, that a reincarnating spirit soul finds parents who allow it to continue on its karmic path? And then there are the famous synchronicities, the so-called coincidences, the fateful moments—aren’t helping spirits needed here, too, who support the workings of karma “from the other side”? The so-called dead also play a role here, as part of the whole of reality, not only insofar as we think of them but also insofar as they are spiritually interwoven into our daily lives. Karma, as a principle of moral compensation, is a structure that supports the world, and we are existentially integrated into its fabric—in the “hereafter” of processing our past life and preparing for the next one and in the “here and now” with its potential moments of destiny—every day.

Karma is not a Clockwork

But these threads of destiny are not part of a puppet theatre, and the logic of this fabric is not that of a clockwork. One key feature of modern thinking about karma is that karma is no longer seen as the opposite of freedom but, on the contrary, as a consequence of taking our freedom seriously. Everything that is an effect has a cause—also in human life. As responsible beings, we are confronted with the consequences of causes that we ourselves bring into the world. As long as we limit ourselves to one biographical existence, this idea is hardly controversial: if I eat poorly, that will have consequences for my health. If I treat people badly, they will turn away from me. In the event of a certain level of transgression, earthly law courts come into play.

The situation is more complex with karmic connections, because I cannot easily tell from the events of my life how and whether they have anything to do with consequences from previous lives. What is the effect here, and what is the cause? And don’t I also have the opportunity at every moment to react freely to the things I encounter? Destiny is also always the time right now!

Unfortunately, our reason has a strong affinity to mechanical thinking. If we think about karma mechanically, then judgements can indeed arise in which we confuse these levels: then victims “must” fundamentally be “to blame” for their suffering because that is how karma “works”. And some people callously say (or think): “After all, you yourself wanted everything this way; that’s just karma.” But that would not only be an overreach, it would also lack a deeper reality because such situations cannot be judged from the outside at all. In any case, it’s a steep hill to climb for opponents.

Not Related to the Past

Another important aspect in this context is that karmic compensation has nothing to do with “punishment”, as is often implied. Nevertheless, archaic images continue to act in the collective depths. In popular attitudes in India, for example, it is quite common for negative circumstances in life to be interpreted as karmically (self-)caused, sometimes even by those affected themselves, and for their consolation because patiently bearing misfortune prepares a better future life.

Although there is no karma thinking in the Abrahamic religions, here, strokes of fate were seen as acts of divine punishment, although this explanation didn’t actually work with Job, and it also proved to be incorrect with the “healing of the man born blind” in the Gospel of John. Nevertheless, both the contemporaries of the Old Testament patriarch and those of Jesus could only explain misfortune as a punishment from God—and this continues to have an effect right up to the present day.

In Steiner, however, the category of punishment is nowhere to be found in connection with karma. Compensatory events are much more subtle. In the lectures on the Manifestations of Karma from 1910 (GA 120), Steiner gives an example: in the review of their past life after death, an individual comes to the moment where they hit a person. This, however, does not lead to having to experience something bad in the next life “to compensate” but rather to doing something good for the other individual who was harmed at the time. In another context, Steiner speaks explicitly of “good deeds” as compensation in a next life (CW 155).1

Indeed, it is astonishing how many constellations Steiner describes where an event of destiny has nothing to do with the past but with preparation for the future. In the lecture of 24 October 1916, for example, he characterises misfortunes that result in a violent end to life not as compensatory processes from the past but as strengthening the I for a future incarnation (CW 168).2

Fundamentally, Rudolf Steiner warns us not to make things too easy for ourselves with supposed karmic explanations, for example, by rashly declaring being hit by a falling brick to be a karmic necessity. This is not at all necessary, he says. In every person’s life, events constantly occur that have absolutely nothing to do with their merit or guilt in the past (GA 34).3 Elsewhere, Steiner says that although karma was the great law of cosmic justice, it should not be understood in a fatalistic way (CW 94).4 In connection with illnesses, above all, we should not obsessively think of effects from the past (GA 224).5 The same applies to congenital physical and mental disabilities. Bearing this in mind prevents misunderstandings and rejection from critics of esotericism.

Conclusion

The idea of reincarnation and karma leads not just to a new view of our lives and our relationships. It also inevitably leads to a complete paradigm shift in our view of reality. Every intimation—however small—of the reality of the workings of destiny and thinking through its implications for our worldview cracks the surface of materialism like the famous seedling that pokes its head through the road surface. Seen in this light, nothing is as effective in overcoming materialism as the idea of reincarnation and karma—an idea as old as humanity—and yet still in its infancy in terms of being understood.

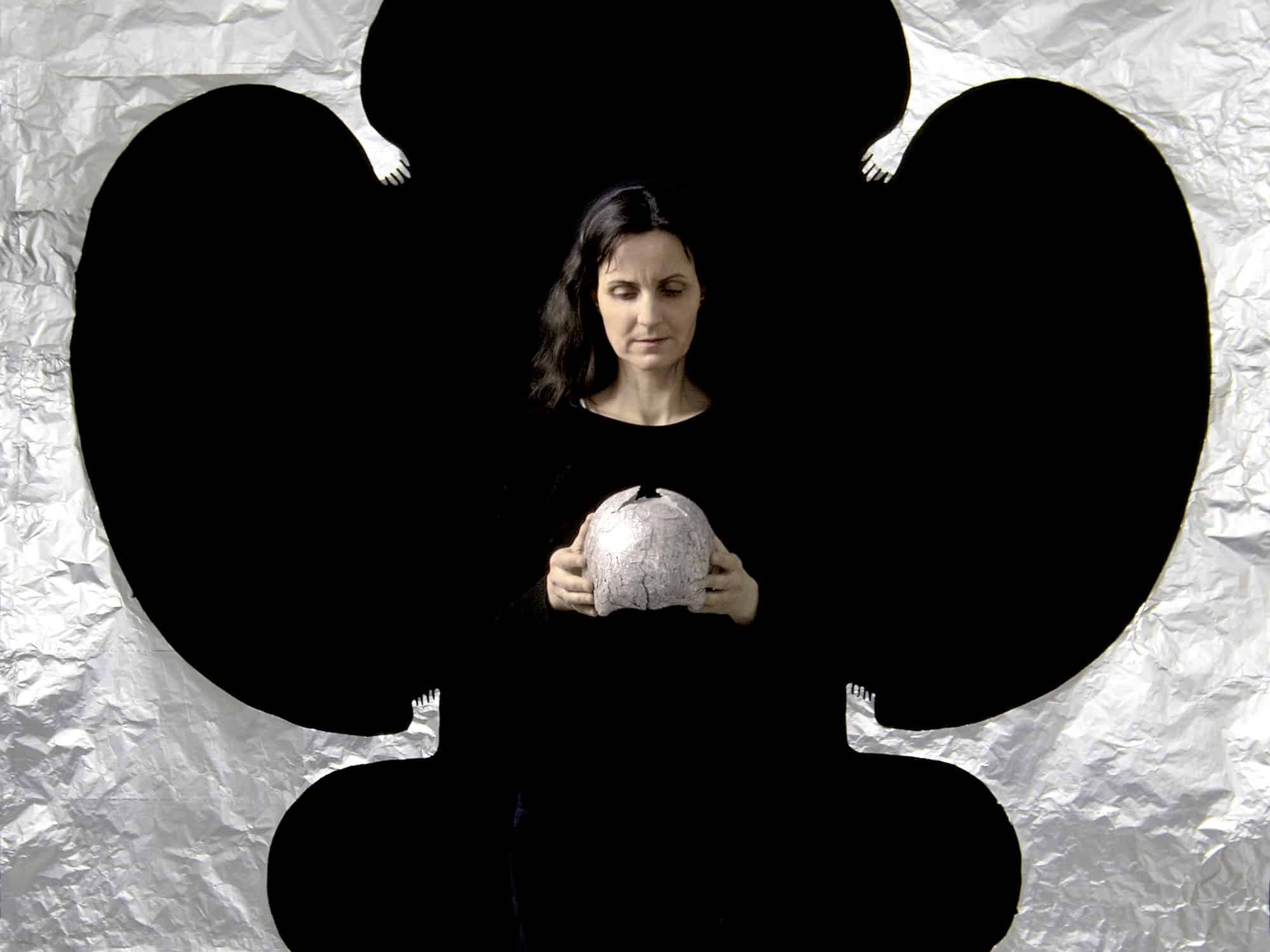

On the artwork by Jochen Breme

Behütung Installation, sculptural objects, photographs. Gallery “Kunst 77,” Bonn 2006. Studio and exhibition images: Bernd Zöller.

Eight people each placed in front of a large membrane made of aluminium foil. A flower-like flat figure was cut out of the aluminium foil and formed into a baroque-looking hat by gathering and compressing the material. In a second moulding process, four of the eight hats were forged together over a plaster cast of each person’s head, as if over an anvil, to form a fragmentary skull shape. The four skull moulds are presented on pedestals, the four other hats on the corresponding skull anvils. The eight remaining edge pieces of the aluminium membrane were forged over glass bottles and across the floor and the resulting conglomerate placed in the gallery’s display window. The studio photographs, which show this process using the example of four people (figure in front of silver background, figure with hat, figure with skull), were juxtaposed with photographs of the eight people with hats, which were taken in everyday urban life.

More Jochen Breme

Translation Christian von Arnim

Footnotes

- Rudolf Steiner, Christ and the Human Soul, CW 155 (SteinerBooks, 2023).

- Rudolf Steiner, The Connection between the Living and the Dead, CW 168 (SteinerBooks, 2017).

- Rudolf Steiner, Grundlegende Aufsätze zur Anthroposophie und Berichte aus den Zeitschriften «Luzifer» und «Lucifer – Gnosis» 1903 – 1908 [Basic essays on anthroposophy and reports from the journals “Lucifer” and “Lucifer-Gnosis” 1903 – 1908], GA 34 (Rudolf Steiner Verlag, 1987).

- Rudolf Steiner, An Esoteric Cosmology. Evolution, Christ and Modern Spirituality, CW 94 (SteinerBooks, 2008).

- Rudolf Steiner, Die menschliche Seele in ihrem Zusammenhang mit göttlich-geistigen Individualitäten [The human soul in its connection with divine-spiritual individualities], GA 224 (Rudolf Steiner Verlag, 2015).

although we accept entropy in our material existence humans seem as yet unable to apply the cosmic truths to themselves .. there is no loss or gain of energy .. humans are a periodic mass of energy imbued with spiritual/feeling, physical/thinking, forces/will. Some of us have the ability to observe these thoughts/forces in our individual consciousness by creating momentary ‘gaps’ of awareness which enables vision beyond or outside of the ‘present’ moment. Thus like tectonic plate theory was laughed at when initially presented, so to will thoughts that all human life that has ever lived is still in human form at this very moment. There is no loss or gain of energy, only it’s distribution varies within the greater cycles of the universe. This will all be understood in time that light has made ..