Rudolf Steiner met the poet and bon vivant Otto Erich Hartleben (1864–1905) in Weimar, together with whom, for several years, he would later publish the Magazin für Litteratur [Magazine for Literature]. Hartleben was known for his “wet and wonderful” lifestyle. It’s said that he paid extensive homage to Dionysus and Eros.

Hartleben had initially studied law at the request of his grandfather, with whom he had grown up after the early death of his parents, and worked briefly as a court clerk. In 1890, however, he settled in Berlin as a freelance writer. In 1893, he married his long-time lover Selma Hesse, whom he called “Moppchen” [Mopsy]. The poet regularly attended the annual Goethe gatherings in Weimar, although he always slept through the actual events. It was only in the evenings that he found himself in the “circle of journalists, theater people, and writers who gathered at the Hotel Chemnitius on the evenings of the Goethe festivals . . . .” “Why he was sitting there,” said Rudolf Steiner, “I knew at once: He was in his element, he loved to live it up, in the kind of conversations cultivated there. He stayed there awhile. He wholly couldn’t leave at all.”

The acquaintance between Rudolf Steiner and Otto Erich Hartleben developed by way of Schopenhauer: “Many admiring and dismissive words had already been spoken about the philosopher. Hartleben had been silent for a long time. Then, in the midst of wild conversational revelations, he said, ‘One is stimulated by him; but yet, he’s not right for life.’ He watched me questioningly with a childish, helpless look. He wanted me to say something because he had heard that I was studying Schopenhauer. And I said, ‘I must take Schopenhauer for a narrow-minded genius.’ Hartleben’s eyes sparkled; he became restless; he finished his drink and ordered a fresh glass; he’d taken me to heart in that moment; his friendship with me was established. ‘Narrow-minded genius!’ He liked that.”1

Milieu of Freedom

It was on one of these evenings that the first of the Serenissimus anecdotes was written (later known through the magazine Jugend [Youth]), which were based on the Weimar Grand Duke Karl Alexander—representative of the so-called petty princes, the rulers of dwarf states—and in which his absent-minded and affable demeanor was lampooned. The Grand Duke would turn to the people he had dealings with full of sympathy and interest, but often without being clear about the concrete situations. Rudolf Steiner recounts the “original anecdote” in his lecture of October 27, 1918: “Serenissimus visits his country’s penitentiary, and wants to have a convict brought before him . . . . He then asks this convict a series of questions: ‘How long have you been held here?—I’ve been here for twenty years.—Nice time that, nice time, twenty years, nice time that! What has caused you, my dear fellow, to take up residence here?—I murdered my mother.—Ah so, so! Strange, most remarkable! Indeed, tell me, my dear, how long do you intend to stay here?—I’ve been sentenced to life imprisonment.—Remarkable! Nice time that! Nice time! Well, I don’t want to take up any more of your precious time with questions. My dear warden, this man will have the last ten years of his sentence remitted with mercy.—Well, that was the original anecdote. It was by no means the result of a malicious mood, but rather a humorous take on something that, if necessary, could also be taken in all its ethical values and so forth. I’m convinced that if it had ever happened that the personage to whom this anecdote was often, perhaps wrongly, directed had read it himself, he would have laughed heartily at it.”2

According to Rudolf Steiner, the mood that lay over the circle around Hartleben “most certainly belonged to the milieu of the Philosophy of Freedom, for the mood of the Philosophy of Freedom, at least, lay over the circle that I frequented.”3 “Every evening,” reports the painter Josef Rolletschek, “we sat in the glass veranda of the Hotel Chemnitius and Hartleben told his first Serenissimo jokes there. Then, he began to philosophize with Steiner, and the same thing was always repeated: The more advanced the hour, the cloudier Otto Erich’s brow became, the more unobjective his discussions, and Steiner calmly and matter-of-factly took the lead.”4

Arranging Poems

Then, one night (as Rudolf Steiner once told Ernst Lehrs on a long car trip), there was a knock at his window. “The pitiful voice of Otto Erich Hartleben” rang out with a request to let him in: “Hartleben entered, his whole body trembling: ‘Let me stay here, I can’t possibly go home again. When I went into my room earlier, I saw a cockroach on the floor.’ Rudolf Steiner knew that Hartleben had an almost pathological fear of insects and realized that he had no choice but to get dressed again and keep him with him for the night.” Now the friends used the night hours to compile a Goethe Breviary. According to Lehrs, Rudolf Steiner “brought the volumes of poetry from his two editions of Goethe from his library, along with all the paper he could find in the apartment and the necessary glue. They went through, poem by poem, and when one of them found favor before their eyes, the page in question was taken out and glued onto a sheet of paper.”5

The poems were arranged chronologically and given headers that provide information about the respective biographical stages associated with the poems; for example, above “Heidenröslein” [Heather Roses]: “Friederike.—Sent to Herder, 1771.”6 This then required a preface in which they “didn’t exactly treat the philologists lightly.” “They especially had it in for the philologists. According to the preface, it is thanks to their diligent research that the dates of the individual poems are known, but they would not have thought of organizing such a chronological edition themselves. . . . And then literally: ‘But what do philologists come up with—nothing.’7 Rudolf Steiner quoted this sentence to us with amusement. It was thereby clear that the various ‘impertinent remarks’ in the preface were by no means the sole responsibility of Hartleben.”8

One’s Own Taste as a Guideline

In the preface itself, however, Hartleben doesn’t mention the participation of a second person: “When I joined in the celebrations of the Goethe Society in Weimar this spring,” says Hartleben, “I was—standing at the tender age of thirty—the youngest among those rejoicing; the overwhelming majority of the participants were all gracefully moving toward the turn of their sixtieth year.—This agedness in today’s reverence for Goethe is a rather grave and sad sign: And since I love Johann Wolfgang Goethe with all my heart, I decided to do what I could to keep him alive for my generation. And I came to the conclusion that more than twenty learned Goethe Yearbooks, full of the keenest acumen, could afford a single edition of the poems that would meet the naive desire for enjoyment without pretensions. There was only one guideline for such a book: one’s own taste. I had to create a book—entirely for myself: The more arbitrary and individual, the better and fresher it would be.”9

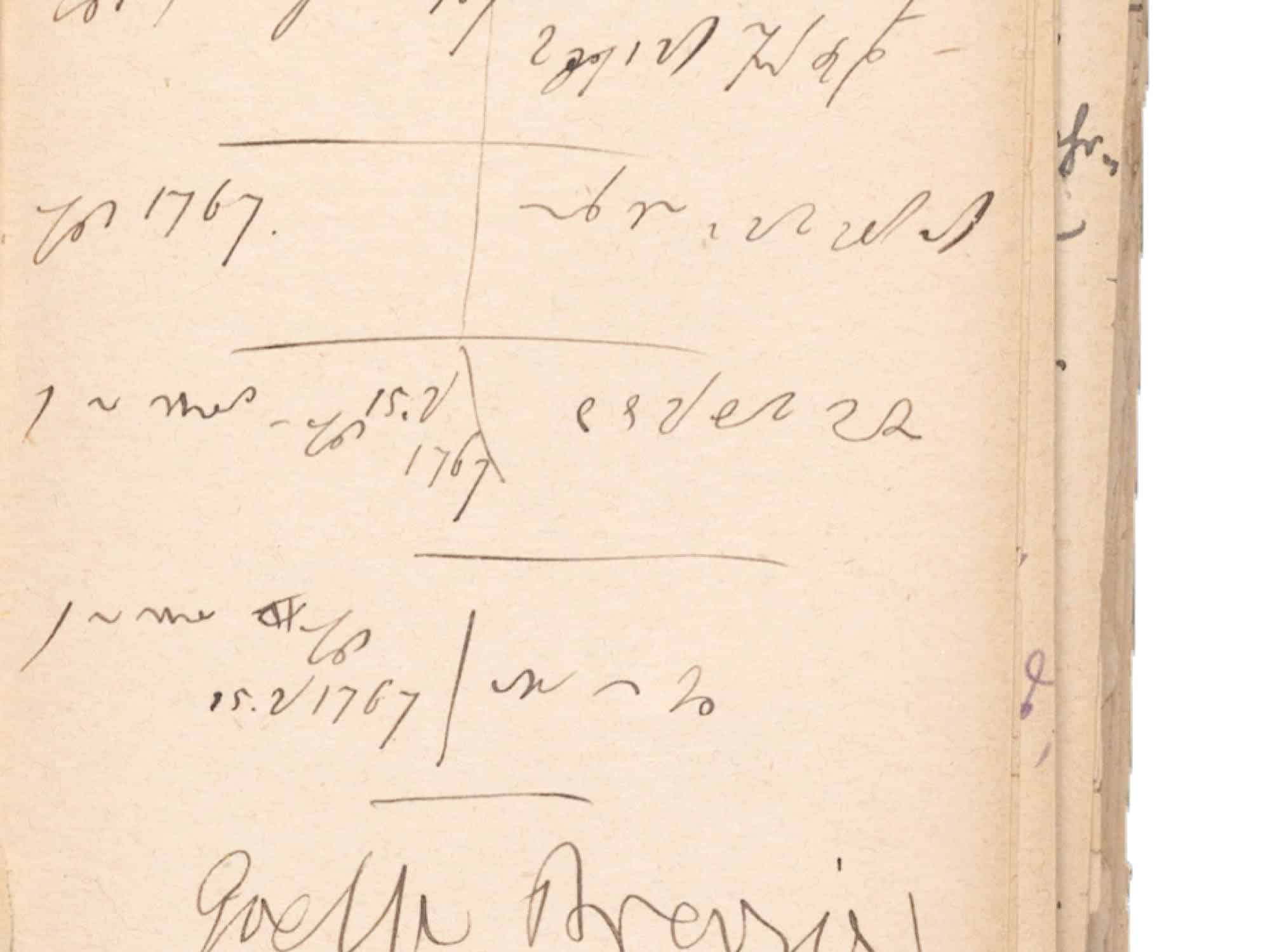

So did Rudolf Steiner contribute to the book or not? There are now interesting documents in the Rudolf Steiner Archive [Dornach] that support Lehr’s version—even if the two men may not necessarily have been working with scissors and glue that night. Rudolf Steiner’s notebook #324 from 1894 contains many pages of stenographic notes in a kind of two-row table: One row contains the header lines of the Goethe Breviary; next to it are the beginnings of the poems. This table was probably the first draft of the book that night, as the printed version still shows some changes.

And further, Rudolf Steiner also received the typeset manuscript at one time. Hartleben wrote to his wife on July 14, 1894: “My manuscript is now with Dr. Steiner, who is looking through it, then I will give it to [Eduard von der] Hellen.”10 Presumably, there’s also a sheet from this manuscript review in the Rudolf Steiner Archive (see photo), on which Rudolf Steiner corrected some of the headers again. These corrections were also taken into account in the print, which exhibits a different page numbering compared to this sheet.

Beyond Death and the Devil

The Goethe Breviary was republished in 1901 and expanded to include several poems, mostly from the aged Goethe, and a second preface, which Hartleben had written after a life-threatening health crisis. Apparently, new aspects of Goethe had come to his attention in the meanwhile, which he wanted to integrate into the new selection: “In our struggle for a unified worldview that could replace the old one of the beyond, death, and the devil, the aging and aged Goethe of the nineteenth century is a mighty ally. He experienced inwardly that, on account of our need and desire, we must pass through the hollow alley of exact natural science, if we want to reach that which we promise ourselves in our hearts and which only can fulfill us, that ‘view of daylight’—there is no other way to Küssnacht. And yet we all want to go to Küssnacht.—Every enrichment of our knowledge of nature—a deeper penetration into the essence of God; every new proof of the psychic through a physical parallel—a further view of the total-ensoulment of matter: This was the only way Goethe could think ‘materialistically,’ and that there could be human beings whom this path could lead to desolation, to pessimism, he probably never believed with a smile: What more can the human being gain in life / Than that God-Nature reveals itself to him— / How it lets the solid melt away to spirit, / How it firmly preserves that which is spirit-generated.”11

It seems as if he had an inkling of what had indeed interested Rudolf Steiner so much in Goethe as the editor of his scientific writings! And so it is touching that—although the friends had completely grown apart in the meantime—Otto Erich Hartleben sent Rudolf Steiner a copy with the dedication: “To Rudolf Steiner, in grateful memory of Weimar days / Otto Erich.”12

Is this to be read as an indirect acknowledgment of his friend’s significant collaboration in the creation of the Goethe Breviary? Otto Erich Hartleben’s brother, retired lieutenant Otto Hartleben (1866–1929), who was also a friend of Rudolf Steiner, asked him in a letter dated November 9, 1901: “What do you think of Erich’s second preface to the Goethe Breviary?” Rudolf Steiner’s answer, as much as it would interest us, has not survived—perhaps, it was only spoken.

Translation Joshua Kelberman

Footnotes

- Rudolf Steiner, Autobiography: Chapters in the Course of My Life, 1861–1907, CW 28 (Great Barrington, MA: SteinerBooks, 2005), pp. 119–120.

- Rudolf Steiner, From Symptom to Reality in Modern History, CW 185 (Forest Row, East Sussex: Rudolf Steiner Press, 2015), lectures in Dornach from Oct. 18–Nov. 2, 1918. The one told here by Rudolf Steiner, signed O. E. H. by Otto Erich Hartleben, can be found in the Munich magazine Jugend [Youth], no. 30 (1896), p. 482. The painter Curt Liebich, a friend of Rudolf Steiner, recounts in his memoirs that the Grand Duke was once shown new districts in Jena, and he asked: “Have these houses all been built here?” Carl Liebich, “Aus meiner Weimarer Zeit” [From My Time in Weimar] Freiburger Zeitung [Freiburg Newspaper] (June 17, 1931).

- Ibid.

- Joseph Rolletschek, “Begegnungen mit Rudolf Steiner” [Encounters with Rudolf Steiner] Neues Wiener Journal [New Vienna Journal] (June 29, 1928).

- Ernst Lehrs, “Rudolf Steiner und Otto Erich Hartleben,” Mitteilungen aus der Anthroposophischen Arbeit in Deutschland, no. 70 (1964), pp. 233–238.

- Otto Erich Hartleben, ed., Goethe-Brevier: Goethes Leben in seinen Gedichten [Goethe Breviary: Goethe’s Life in His Poems] (Munich: Schüler, 1895), p. 30.

- Ibid, p. XV; The exact quote is: “One might now be surprised that the gentlemen, after all their sour preparatory work, did not come up with the idea of organizing such a chronologically ordered edition themselves. But, dear God—what philologists don’t come up with!”

- See footnote 5, pp. 235 f.

- See footnote 6, pp. XV f.

- Otto Erich Hartleben, Briefe an seine Frau 1887–1905 [Letters to his Wife, 1887–1905] (Berlin: Fischer, 1908), p. 187.

- Otto Erich Hartleben, ed., Goethe-Brevier: Goethes Leben in seinen Gedichten [Goethe Breviary: Goethe’s Life in His Poems], 3rd edn. (Munich: Schüler, 1905), p. XIX. Trans. note—The last four lines are from the poem by Goethe, “Bei Betrachtung von Schillers Schädel” [When Observing Schiller’s Skull] (1826). Küssnacht, Switzerland is featured in the legend of William Tell as the place he is taken to be imprisoned after shooting an arrow into the apple on his son’s head and threatening to shoot another at the bailiff; but, their boat shipwrecks and he is pursued, only to ultimately shoot the bailiff near Küssnacht; then, Tell met with the representatives of the three Swiss cantons to form the Swiss Confederacy; all, according to the legend, around 1307. Goethe, during a trip in Switzerland in 1797, thought to write an epic poem about William Tell, but instead passed his materials on to Schiller, who wrote the play, Wilhelm Tell [William Tell] in 1804, with the lines by Tell: “Through this ravine he needs must come. There is no other way to Küssnacht,” Friedrich Schiller, Wilhelm Tell, trans. Theodore Martin (New York: Heritage, 1952), act IV, scene III; cf. Margrit Wyder, Barbara Naumann, Robert Steiger, Goethes Schweizer Reisen [Goethe’s Swiss Journeys], 2 vols. (Basel: Schwabe, 2023); H. E. Marshall, Stories of William Tell and His Friends: Told to the Children (New York: Dutton, 1908).

- Martina Maria Sam, ed., Rudolf Steiners Bibliothek: Verzeichnis einer Büchersammlung [Rudolf Steiner’s Library: Index of a Book Collection] (Basel: Rudolf Steiner Verlag, 2019), index no. Gö 300.