Biodiversity is a hot topic in academia today. It seems that wherever civilization spreads, species diversity dwindles—natural habitats are lost, and the landscape becomes fragmented. If nature reflects our thinking, can we change this?

On one hand, with the loss of natural habitats, environmental toxins, introduction of foreign species, hunting, overgrazing, overfishing, exploitation, and deforestation, we see how civilization can have a negative impact on biodiversity. In short, we’ve used nature for our own purposes, and the extinction of species reflects our objective thinking, which is largely subordinate to our desires and leads to separation from nature. At the same time, the development of cultural landscapes in Central Europe, for example, after the Middle Ages, when the Cistercian monks developed nature in a particular way, and plant and animal species flourished, shows that civilization can also contribute to diversification. If we observe nature unconditionally, we find that we human beings are mirrored there. If we look at these two opposite possibilities, the suffering that we see in the first case is a picture of our dead thinking and fragmented consciousness. The self-knowledge that we could gain from this is that we are responsible for our actions. If it keeps going in this direction, it will be our demise. But we can change this.

Diversity creates a wealth of coexistence, namely in relationships between different plants and animals. From this wealth of relationships, the entirety of an ecosystem, a habitat, is formed. This becomes critical when the relationships change. Diversity can buffer unforeseen influences—it tolerates impulses from outside and even needs them so that constant development can follow.

It is the same for a farm, a school, or a company—diversity is necessary to create a distinctive identity. What is particular about this farm or that school? What is the landscape calling for? What is the leading thought here, and how do we want to develop it? How can it be anchored into this place? How can we connect the social and human aspects with the environment? It’s always a question of balance between thinking, feeling and willing—and of how diversity and identity work together.

Those who are most likely to make mistakes are those who try to address one isolated fact with their powers of thought and judgment. Those who have achieved the most, on the other hand, are those who do not stop working through all the different aspects and modifications of a single experience or a single experiment in every possible way. Since everything in nature is in eternal action and reaction, every phenomenon is connected with countless others.

The Task of the Scientist

Goethe was far ahead of his time when he wrote in his essay “The Experiment as Mediator of Subject and Object:”

[W]e accomplish most when we never tire in exploring and working through a single experience or experiment by investigating it from all sides and in all its modifications. … [S]ince everything in nature, especially the more common forces and elements, is in eternal action and reaction, we can say of every phenomenon that it is connected to countless others, just as a radiant point of light sends out its rays in all directions. Once we have carried out an experiment, we cannot be careful enough to examine other bordering phenomena and what follows next. This is more important than looking at the experiment in itself. It is the duty of the scientist to modify every single experiment. This is the opposite of what a writer does whose aim is to entertain. Writers who leave no room for roaming thought bore their readers. Scientists must work ceaselessly, as if the goal was to leave nothing for future generations to accomplish.1

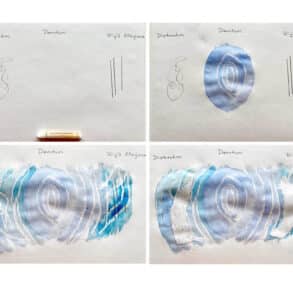

This is what we have to look at more closely. The diversification of every individual experiment is the real task of natural scientists. Goethe describes it as a matter of putting together the diversity in such a way as to reveal the essence of a thing—be that in a plant, a type of animal, or a series of specific physics experiments. This he calls a higher experience in experience. This activity holds true not just for natural scientists but for all people interested in nature and social issues!

Diversity also Strengthens Human Identity

Each and every one of us can be seen as a species of the human genus. We ourselves contribute to this identity. How do we live? What do we eat? Our immune system is of great importance for our physical and etheric body. It is strengthened by the effectiveness of the higher elements in our ego organization. The more intensive and varied our interactions in the natural environment and also in a social context, the more different and individual our experiences are. These experiences are reflected in our microbiome, which is part of our immune system. The more diverse our immune system is, the stronger our individuality and identity are. It can be shown that in the course of healthy aging, the human microbiome becomes more and more individualized—each person becomes more specifically different from other people. Diversity always strengthens identity—the relationship between diversity and a strengthened identity is not only true for nature and ecosystems but also for communities and individual human beings.

These are excerpts, lightly edited, from the talk given at the conference.

More Natural Science Section: Evolving Science 2024

Translation Laura Liska

Image Meinhard Simon during his presentation. Photo: Johannes Kühl

Footnotes

- Translation by Craig Holdrege. (The Nature Institute, In Context Issue #24) Goethe wrote this essay in 1792, and it was published for the first time, in a slightly altered version, in 1823. Source of translation: “Der Versuch als Vermittler von Objekt und Subjekt,” in Goethe’s Werke, Hamburger Ausgabe, Bd. 13 (Munich: Verlag C. H. Beck, 2002, pp. 10-20).