October 1, 1924 to March 30, 1925—“A sudden end [to the September courses]: Rudolf Steiner’s illness set in. The situation changed completely. I left the clinic to nurse Dr. Steiner with no idea of the difficulties to come,” wrote Ita Wegman years later.1 On Tuesday, September 30, 1924, she sent urgent telegrams to her medical colleagues Ludwig Noll and Eberhard Schickler, asking them to come to Arlesheim to support the clinic during her absence, and for Noll to help her with Rudolf Steiner’s treatment. One day later, on October 1, Steiner bid farewell to House Hansi: “I’m going up [to the studio] for two days,” he told Helene Lehmann. In the end, Steiner was ill for six months and never returned from his studio in the Carpentry Workshop. Helene Lehmann remembers: “He comforted me when I looked frightened.”

The day before, September 30, Marie Steiner-von Sivers traveled to Germany for a week-long tour with the Goetheanum Eurythmy Ensemble. Seeing Steiner’s state of health, she didn’t want to go. On October 2, he let her know that he’d moved for his treatment and care: “So, I’m here and will stay only as long as necessary.”

The First Days of Treatment

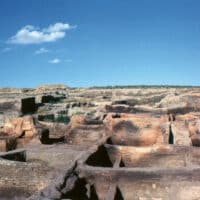

Steiner didn’t go to Ita Wegman’s Clinical Therapeutic Institute in Arlesheim. He went to his room at the Goetheanum, the room he knew so well, where he’d worked for nearly ten years—his “sculptor’s studio,” where many works and very important conversations had taken place. He went to the site of the wooden sculpture of Christ. Six months later, he died next to it. He had only just managed to finish the six parallel courses in September—70 lectures, 400 individual discussions, and countless other activities,2 including the short address on the day before Michaelmas—then his forces were exhausted. “[With the September courses], it was as if Rudolf Steiner set himself to do everything he could to still achieve some things spiritually,” wrote Ita Wegman. He did it out of a “sense of duty to higher powers,” he wrote to Marie Steiner-von Sivers from his studio on October 6. In the weeks that followed, he emphasized again and again that he could summon the forces for the courses in September just fine, but not for the endless personal concerns, worries, and wishes of the members.

With a handwritten notice attached to the bulletin board in the Carpentry Workshop on October 2, Rudolf Steiner canceled the upcoming lectures that had already been announced; a week later, on October 10 (and soon afterwards in the members’ News Sheet in the weekly Das Goetheanum), he called for an end to any and all speculation by members about his state of health, to all “rumor-mongering in anthroposophical circles.” He hoped that through the “uniquely sacrificial care of my dear friend Ita Wegman and her faithful helper Dr. Noll,” it would soon be possible to return to “physical activity, without which, unfortunately, the spiritual cannot work upon the Earth, at least to a certain extent.” Then he added, “But in the end, everything must be perceived according to destiny (karmically).”

Regardless, many members continued to press Rudolf Steiner with letters full of questions, wishes, and concerns. “The Doctor has become ill precisely because one always burdens him with such questions,” Ita Wegman replied, and “[p]eople don’t seem to know how ill the Doctor actually is.” Steiner wrote to Marie Steiner-von Sivers about the etiology of his illness, saying that he had told her some time ago “how, since January 1923, the connection between the higher members of my being and my physical body had not been well.” He had become “very estranged” from his physical body, “not in connection” with it, which had “resulted in a labile balance of the physical forces.” Looking back, Ita Wegman emphasized that there had been a “strong loosening of the etheric body to the point of partial separation of the etheric body from the physical body.” “‘Compared to other people, I have actually already died on the Earth,’ he [Rudolf Steiner] often said, ‘my “I” and my astral body direct the physical body and supplement the etheric.’” According to Ita Wegman, Steiner held on to his body with superhuman forces of will after the destruction of the Goetheanum by fire—an attack that by no means affected the building alone but also the master builder and his life forces. Since then, his nourishment, the internalization of foreign substance that the etheric body requires, was difficult and ever more difficult.

Silence and Struggle

“We lived in quiet seclusion,” Ita Wegman emphasized—and Marie Steiner-von Sivers asked Rudolf Steiner in a letter dated October 9, 1924, “Do you actually see people apart from those caring for you?” She understood his answer, “All contact with people affects me terribly.” His secretary Guenther Wachsmuth with the daily mail, Albert Steffen concerning the weekly journal, and Ernst Aisenpreis with questions about the new building were allowed to come for brief moments of the day, as were Mieta Waller from House Hansi and Marie Steiner-von Sivers on her return from tour. He wrote of his necessary recovery and hoped he would soon get better, but also, “I must stop everything ‘destructive.’” He had already spoken of the “short life” that was still available to him in a lecture in 1919.3

The situation was difficult. “He bore his illness with patience and dignity,” Ita Wegman recorded, but also: “He suffered unspeakably from feeling his physical forces gradually dwindling, from having to receive more and more care.” This is also mentioned sporadically in Rudolf Steiner’s letters to Marie Steiner-von Sivers; he was “not at all equipped” to “devote such hours to his own care.” “We can offer such health-giving help to others—to help ourselves, we must appeal to others.” “It’s just not at all in keeping with the way I actually want to live and work.” Rudolf Steiner wanted to and needed to continue working during this decisive situation of the anthroposophical movement, to go to Berlin for a large number of meetings and public events in large, rented halls such as the Berlin Philharmonic Hall. But this was now unthinkable. Since the Christmas Conference, everything had only just begun—the refounding of the Society and the School for Spiritual Science, establishing the individual Sections (faculties, departments) of the School, the inner path of the Michael School, and the ongoing development of all other anthroposophical institutions. Rudolf Steiner had been stopped and now could no longer leave his studio. “Try to get along with everyone peacefully. It’s important now to keep the Michael stream moving forward. Those who trust you will certainly come; the others will simply stay away; this they must know themselves. Just make the First Class lessons rich in content and earnest, then you will do a good job,” wrote Ita Wegman on October 16 to the Class holder Anna Wager Gunnarsson, who’d turned to her with questions about passing on the Class mantras and about the Swedish translation.

What made things difficult for Rudolf Steiner—next to everything else—were the debates concerning the second building, the “Michael Castle” [Michaelburg] as he called it to Ita Wegman. The building would be the site of the Independent School for Spiritual Science, which was to be active with impulses for change and initiatives in many areas of life of the endangered civilization, as the real School of Michael in the age of Ahriman. Steiner had received the building permit from the canton of Solothurn in September 1924 despite objections from the Swiss Association for Homeland Protection [Schweizerischen Vereinigung für Heimatschutz], who had assessed the planned building as an “overpowering monument” and “presumptuous” with “grotesque” forms, as “insane arrogance” and a “permanent insult to the eye.” They were supported by the Society of Swiss Painters, Sculptors, and Architects [Gesellschaft Schweizerischer Maler, Bildhauer und Architekten] in June 1924, who predicted that the “shameful cultural monument” would damage the whole of Switzerland. Rudolf Steiner wanted to build “as quickly as possible”; but during his illness, he saw just how energetically the opposing side went to work after the building permit was granted. On October 25, the richly illustrated article “Das sogenannte Goetheanum in Dornach” [The so-called Goetheanum in Dornach] was published in the Schweizerische Bauzeitung [Swiss building newspaper] and was included as a special edition in many local papers, such as the Tagblatt für das Birseck, Birsig- und Leimental [Daily newspaper for the Birseck, Birsig and Leimental regions]. It welcomed the destruction of the first building and called for the “disappearance of the foreign intruder from the Birseck landscape”; Steiner was suspected of “heresy and seduction of the people.”

Rudolf Steiner then spoke out once again, nolens volens, and published two articles with illustrations of the building model in Basel newspapers at the end of October and beginning of November 1924 (“Der Wiederaufbau des Goetheanum” [The rebuilding of the Goetheanum] and “Das Zweite Goetheanum” [The Second Goetheanum] respectively.) On November 23, the Action Committee [Aktionskomitees] against the building called for a large mass protest meeting in the Arlesheim schoolyard and passed a resolution, only to be rejected four days later by the Dornach municipal council [Gemeinderat]. On December 3, Rudolf Steiner and Ita Wegman wrote a letter from his studio thanking the Dornach municipal council on behalf of the Anthroposophical Society but also indicating “that it would probably be for the best if we focused on the building, and did not participate in public discussions. We do not want to disturb the peace in any way and therefore will not participate in public discussions as long as that is possible.” (“I must stop everything ‘destructive.’”)

Nevertheless, Steiner also personally replied to the chairman of the Swiss Association for Homeland Protection, to his proposal to accept bids for the building project and to have a competition for ideas involving non-anthroposophical architects. The proposition to deny anthroposophy the architecture of their own house was not possible. “That would truly be nothing less than spiritual suicide on my part.” But the accusation “that the size of the building was a result of arrogance, presumption, or even some desire for power” hurt him the most, “since I am fully conscious of the fact that I am only doing what is necessary for the matter itself.”

Michael, Ahriman, and Christ

Every morning from around 5 to 8 a.m., Rudolf Steiner continued writing his Leading Thoughts (later known as the “Michael Letters”) and his autobiography Chapters in the Course of My Life (the chapters on Weimar). These texts appeared every week in Das Goetheanum for the public (Course of My Life) and for the members (Leading Thoughts), reaching people all over the world. Steiner couldn’t travel, hold lectures, or have long conversations. Still, he continued to speak to people through these texts and presented the essence of anthroposophy and the spiritual task of the anthroposophical movement in the drama of the twentieth century. He dated the texts he wrote in his studio—and they were published with the date included. He was still there, recognizable by his friends and opponents. By the middle of November 1924, he published statements on the “Michael Path”, “Michael’s Task in the Sphere of Ahriman”, Michael’s “Experiences and Insights during the Fulfillment of his Cosmic Mission”, “Humanity’s Future and Michael’s Activity”; and about the “Michael-Christ Experience in Man”, “Michael’s Mission in the World Age of Human Freedom”, and finally, in unsurpassable drama, about “The World Thoughts in the Work of Michael and in the Work of Ahriman.” Since the beginning of modern times, we were “sliding into another world history.” Human intelligence had become free but also accessible to Ahriman. This was all made clear to the members alongside the whole task facing the Anthroposophical Society and the School for Spiritual Science. Steiner wrote about his contemporaries, like Adolf Hitler, though without naming names and from a spiritual viewpoint: “While man, unfolding his freedom, falls into Ahriman’s enticements, he is drawn into intellectuality, as if into a spiritual automatism, where he is only a limb, no longer his self. All his thinking becomes an experience of the head; but the head sunders his thinking from his own heart life and his own will life and extinguishes his being.”

During these same months, Hitler was working on his own “leading thoughts” while imprisoned in Landsberg, his diametrically opposed program in Mein Kampf [My Struggle]. Ita Wegman wrote a spiritual description of a conversation with Steiner before he went to bed: “One day Rudolf Steiner told me how anti-Michael demons were ruthlessly setting to work to prevent Michael’s work from emerging and to destroy it.” According to Steiner, the decisive factor was whether the Michaelic impulses, so powerfully begun with the Christmas Conference, would be able to break through despite the opposition. “My anxious question was: What will happen if this doesn’t succeed? And the answer was: then karma will prevail.” In a biographical lecture given in London on February 27, 1931, Ita Wegman indicated that Steiner’s illness was a time of intense spiritual confrontation: “I’m passing over the painful hours, weeks, and months of his illness, spent in the studio of the Carpentry Workshop, which I supervised. How he fought against the onslaught of enemy powers in those quiet hours—it’s not really possible to describe.”

“Demons fight every night,” it says in one of Steiner’s notes. Ita Wegman took down some of his statements: “I very much hope to get well again”; “The decision must be made soon, either or . . . .” Most of the six months, though, are not known and the documents handed down can at best be regarded as fragments of a much larger context. Without a doubt, Rudolf Steiner and Ita Wegman continued to work closely together even under the difficult conditions. “Christian Rosenkreutz played a major role in these [joint] meditations,” Wegman emphasized. Despite all the restrictions, Rudolf Steiner tried to develop the School with its Sections and the necessary foundational work. At his request, Ita Wegman asked Karl Schubert on November 21 to transcribe the stenograms of the Curative Education Course for a forthcoming edition (as a publication of the School for Spiritual Science); one week later she was already writing to a Branch leader in Stuttgart about an edition of the Karma lectures from September 1924: “That will be the very next work of the Dr. and as soon as his health permits, he will begin.” In November, Rudolf Steiner also received for a short time Emil Leinhas on behalf of the joint-stock company The Coming Day [Der Kommende Tag], which had to be liquidated (“I was shocked at the sight of him. He was emaciated to a skeleton.”). He also met Ludwig Count Polzer-Hoditz and spoke about the future of the Michael School and its Classes.

Christmas and the Turn of the Year 1924/25

Steiner also didn’t let Albert Steffen’s fortieth birthday on December 10, 1924, just pass by, but had invitations sent out for a celebration. He then sent a personal letter to the gathering honoring Steffen’s work, including his commitment to the Anthroposophical Society. Rudolf Steiner continued to hope that the Anthroposophical Society would become effective and that there would be unity of will in the spirit of Michael, even if he could no longer hold Class lessons and karma lectures.

On December 24, Rudolf Steiner wrote a letter greeting the members who’d come to the Goetheanum for Christmas and gathered in the hall of the Carpentry Workshop. Marie Steiner-von Sivers read it aloud. He called up the memory of the momentous Christmas Conference that occurred in the very same place one year earlier. The Society had been given “a new life” and a spiritual foundation stone had been laid. Steiner again spoke of the “unprecedented sacrificial care of his friend Dr. I. Wegman” and sent on her greetings. Concerning an improvement in his condition and a resumption of his work, there was no mention; days previous, he’d had a fever every evening and been in a miserable state. Notwithstanding, three new, long, and deeply striking texts by him were read out by Marie Steiner-von Sivers at the Christmas gathering (on December 24, 1924, January 1, 1925 and January 2), beginning with “Christmas Contemplation: The Logos Mystery.” On December 28, 1924, the entire Foundation Stone Meditation, now for the first time with the fourth verse, was performed in eurythmy in the hall of the Carpentry Workshop. On January 2, 1925, Rudolf Steiner’s farewell letter to the participants read: “I could only be united with you in spirit this time. Nevertheless, I hope that the forces kindled in your hearts by the Christmas Conference one year ago have received a new impulse.” He “fervently” hoped for this. And he again sent greetings from Ita Wegman.

What the members could not know was, on New Year’s Day, Rudolf Steiner went through an existential crisis with a moment of temporary unconsciousness, on the second anniversary of the fire and exactly one year after his collapse at the “Rout” [social gathering] at the end of the Christmas Conference. A week later, Ita Wegman’s colleague Mien Viehoff wrote to Clarita Berger: “Mrs. Dr. [Wegman] is quite desperate because Dr. [Steiner] is getting weaker and weaker.” Ita Wegman had asked Hilma Walter to always sleep in the anteroom of the studio at night: “Mrs. Dr. [Wegman] finds it terribly lonely to be there all alone.”

Despite all the protests, excavation work for the second building began in January 1925, after the Bern Federal Council [Bundesrat] rejected a new submission from the “Action Committee”; according to the Federal Council, Solothurn’s decision was definitive. Ernst Fiechter, professor of architecture at the Stuttgart Institute of Technology [Technischen Hochschule Stuttgart], came to Dornach to discuss the building with Rudolf Steiner. Steiner was too weak to receive him, but Fiechter was given permission to look at the plasticine model of the Second Goetheanum in the Glass House for a long time: “One had the sense of an indescribably sublime building.” Professor Fiechter set to work campaigning for the building project at the Stuttgart Institute, among colleagues, in front of students, and in specialist journals in Germany and Switzerland. His ten-year-old son Nik had suffered a serious eye injury in the summer of 1924, which had been treated, with Steiner’s support, at the Stuttgart Clinical Therapeutic Institute. Nik was left in Dornach to see Rudolf Steiner. Steiner expressly asked Wegman to make it possible for him to see the boy on Epiphany. Nik later wrote about his encounter in the studio: “I had to walk a few meters through the room alone. The path seemed infinitely long to me. There stood the mighty wooden sculpture that first caught my eye. In front of this statue of Christ, stood Rudolf Steiner’s bed. The closer I got, the more sacred and majestic this last encounter became. Rudolf Steiner sat up in bed and looked at me with eyes that radiated an indescribable love. The physical room disappeared, an expanse arose, accompanied by luminous warmth. What was said, I no longer know. Then he put his hand on my head and spoke the words that accompany me ever since: “All is well.”

The Last Three Months

In January 1925 alone, Rudolf Steiner wrote six more long and trailblazing texts, accompanied by leading thoughts, concerning anthropogenesis out of the world of spiritual hierarchies, and the past and future destiny of the Earth and the macrocosm. Dornach was cold; an epidemic of influenza was raging; the studio could only be heated by a small stove—and everything continued to be extremely modest and scant. Nevertheless, Rudolf Steiner read through his whole Occult Science again for a new edition with a new preface: “Everything I’ve been able to say since then, when inserted in the right place in this book, appears as a further statement of what I was able to sketch at the time.” In the second week of February, he presented a ritual text for the investiture of Friedrich Rittelmeyer as Erzoberlenker of the Christian Community, and for her birthday on February 22, he gave Ita Wegman a central meditation on Ephesus. Five days later, Rudolf Steiner turned 64 in his studio. Marie Steiner-von Sivers wrote to him from Berlin: “Hopefully, this letter arrives in time and brings you all my love and reverence and gratitude from me and from humanity.” Albert Steffen spoke in the Carpentry Workshop hall about Steiner’s life work and read the Foundation Stone Meditation and the Michael Imagination. The Stuttgart Waldorf students sent a large gift box, including an edition of his Mystery Dramas that they’d bound themselves in red and blue leather (“with edges, endpapers, and spine cleaner than any professional bookbinder could ever make themselves,” A. Steffen). The same day, February 27, 1925, Hitler refounded the Nazi party [NSDAP] and held a speech on “Germany’s future.”

As before, Rudolf Steiner fervently wanted to continue working. On March 5, he wrote to Marie Steiner-von Sivers, “I must be able to work soon. After all that’s occurred, it’s not possible to imagine what would happen if the building had to be interrupted on account of my illness.” The shuttering for the columns had already begun and their casting was planned for the end of March. On March 23, however, he wrote her another letter: “Everything is going terribly slowly for me; I’m actually quite desperate concerning this slowness.”

Again, Steiner received Count Polzer-Hoditz, and their conversation again touched upon the Michael School and how its founding was brought about by Ita Wegman’s request: “It was only through this question [of Ita Wegman] that it was possible to establish the Michael School upon the Earth. In this School lies the seed of the future as a possibility. If only this could be understood by the members: as a possibility.” In this context Steiner also said to Polzer-Hoditz, “When you hold the Class lessons, and wherever they are held, bear in mind at all times that you have not to deliver a lecture during the Class lesson, but rather that you are engaged in an act, an act that can connect us with the Mystery stream of all times.” On March 28, Rudolf Steiner signed 13 blue cards for new members of the School.

He continued his Leading Thoughts essays and Course of My Life up to the end of his life. The last completed essay was “From Nature to Sub-Nature.” “The human being must find the strength, the inner power of cognition, in order not to be overpowered by Ahriman in technical culture. Sub-nature must be comprehended as such. This can only be done, if the human being ascends in spiritual cognition at least as far to the extraterrestrial supra-nature, as he has descended in technology to the sub-nature. . . . Precisely by cognitively taking up that spirituality, to which the Ahrimanic powers have no access, the human being is strengthened to face Ahriman in the world.” The last word Steiner added to the manuscript was “cognitively.”

On March 29, Hitler made his first visit to Weimar. In the years that followed, he built it up into a prestigious stronghold of National Socialism (founding the SS and Hitler Youth in Weimar, the “model” concentration camp in Buchenwald, etc.). The same day, Rudolf Steiner handed Ita Wegman the corrected proofs of their medical book, the first ever scientific textbook from the School for Spiritual Science. “He was delighted when he handed it to me: ‘Significant things have been given in the book.’” Steiner asked whether the next-door studio would be ready soon “for him to work on the interior model of the new Goetheanum.” The next day, March 30, around ten in the morning, Rudolf Steiner died.

Book Peter Selg, Rudolf Steiners Atelier: Die letzte Lebenszeit—The Final Years (Arlesheim: Ita Wegman Institut, 2019), dual-language edition

Translation Joshua Kelberman

Title image Rudolf Steiner’s studio, carpenter’s workshop at the Goetheanum. Photo: Walter Schneider

Footnotes

- All quotes from Peter Selg, Rudolf Steiner, Life and Work, vol. 7: 1924–1925: The Anthroposophical Society and the School for Spiritual Science (Great Barrington, MA: SteinerBooks, 2019); Peter Selg, Rudolf Steiners Atelier [Studio]: Die letzte Lebenszeit—The Final Years (Arlesheim: Ita Wegman Institut, 2019), dual-language edition.

- Cf. Peter Selg, “Weit über unser normales Bewusstsein hinaus . . . .” Dornach, September 1924. Rudolf Steiners letzte Kurse [Far beyond our normal consciousness . . . . Dornach, September 1924. Rudolf Steiner’s last courses] (Arlesheim: Ita Wegman Institut, 2024).

- Rudolf Steiner, Die soziale Frage [The social question], GA 328 (Basel: Rudolf Steiner Verlag, 1977), lecture in Zurich on March 8, 1919.