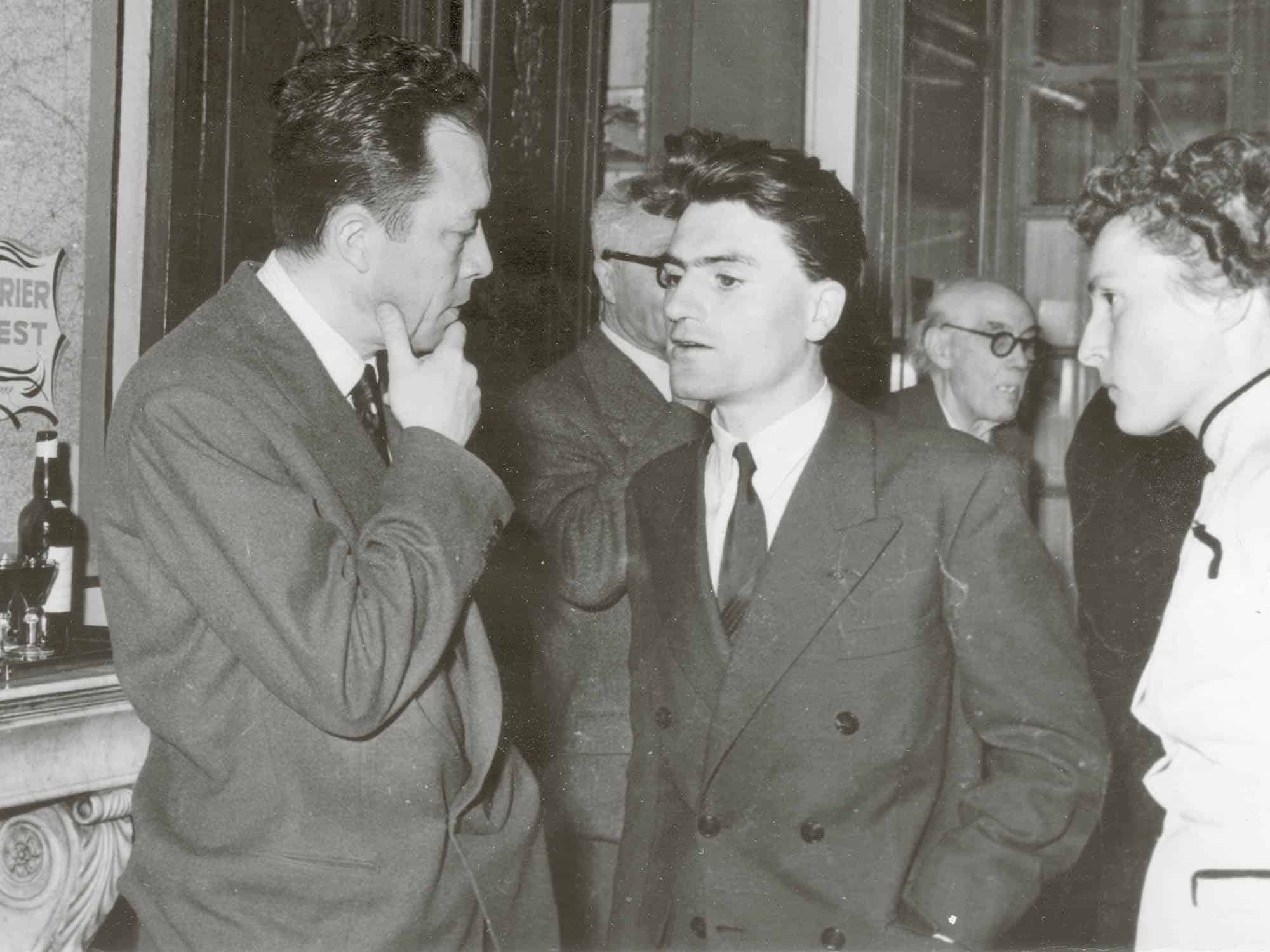

They were handsome, smoked a lot, loved women, nature, and light—and they resisted the Nazi occupation. Albert Camus and Jacques Lusseyran, whose meeting in 1953 was captured by a photographer, are united by their deep search for meaning in a dark world. A reading in dialogue.

The same scene, eleven years apart, two cars: 1960—Albert Camus drives to meet three women with whom he’s arranged a date; 1971—Jacques Lusseyran travels with his third wife. . . . For unexplained reasons, Camus’s car veers off the road and crashes into a tree in the middle of the countryside; Lusseyran’s car suffers a similar fate. In both cars, manuscripts are found: Albert Camus’ is a draft of what (thanks to his daughter Catherine) became The First Man; Jacques Lusseyran’s is a lecture he wanted to hold in Basel before going to the Goetheanum. Both men were 46 years old. They were born eleven years apart and died eleven years apart, in the same way.

But they had very different childhoods. Albert lost his father before he even met him. His mother was deaf and mute. His teacher, Monsieur Germain, paved the way for him by persuading his grandmother (who made the decisions in the house) to allow her grandson to continue his studies after graduating. Jacques, a young Parisian bourgeois, son of an academic, was provided with a love from his parents that became a protective armor for him. This love, full of deep trust, enabled Jacques to live a normal life despite the accident that left him completely blind at the age of eight. His father opened the paths to free spirituality by sharing the fruits of his research in anthroposophical spiritual science.

Albert and Jacques both claimed the essential activity of their childhood was movement. Jacques ran, jumped, and climbed trees. Albert swam and swam and swam until he was out of breath. Later, they both opened to the world of art, images, and ideas. Albert had access to the beautiful library of his uncle Accault, a butcher deeply immersed in culture. Jacques was nourished by concerts his father took him to and powerful images from the stories of his aunt. Later, Albert discovered the magic of the stage through theater, while Jacques was fascinated by the performances his father invited him to at the Goetheanum in Dornach, which he claims to have been able to “see” despite his blindness.

Both carried out brilliant studies in the humanities. Albert Camus studied literature with a focus on philosophy. But, his tuberculosis, diagnosed during his school days, made his life difficult. He was unable to take the French agrégation examination required for teaching philosophy because tuberculosis patients were not allowed to take the exam. He gave up the professorship but not philosophy. He became a kind of “artist-philosopher”: “You only think in images. If you want to be a philosopher, write novels.”1 In 1957, Jacques Lusseyran prepared for admission to the École Normale Supérieure [department of the Paris Sciences et Lettres University] in the field of literature but was excluded from taking the exam by a Vichy decree, which remained in force long after the war, that prohibited the disabled from applying for public service. Only later was he allowed to teach at universities in the US.

Both were encouraged to turn an actual or perceived weakness into a strength. This provided the way for them to unfold their talents and potential. They become writers and artists. Both learned to rely on what was essential: themselves, by tapping into the source of their hunger for life. They both possessed charisma, warmth, and appeal. They knew how to inspire others, how to convey enthusiasm and trust. It was only natural that both of them joined the resistance against the German occupation. Lusseyran built his own group and maintained a relationship with every one of the boys recruited.

The Trial of the Resistance

When Blanche Balain asked him if the deportations were really happening, Camus confirmed: “Indeed, it’s true, so we must take sides and resist.”2 Camus became acquainted with the resistance in Le Chambon-sur-Lignon, where he’d gone to treat his tuberculosis. Courageous individuals, as well as groups from the Protestant population, led and encouraged by the pastors, protected the persecuted Jews. Camus used literature and writing to express his resistance to the occupation. He wrote for Combat, helped distribute the magazine, became editor-in-chief on August 21, 1944, and wrote 155 articles. On August 8, 1945, horrified by Hiroshima and the destructive force of human intelligence, he ended his editorial with the following words: “In the face of the terrible prospects that lie ahead for humanity, we recognize even more clearly that peace is the only worthwhile struggle. It’s no longer a prayer, but an order that must go up from the people to the governments, the order to choose once and for all between hell and reason.”3

The war also gave Camus the opportunity to write the book The Plague, published in June 1947. He knew that “true generosity towards the future consists of giving everything to the present”4, and at the same time, he sensed the potential dangers lying in wait for the future. In the last lines of the book, he warned readers: “[T]hat the plague bacillus never disappears, that it can lie dormant for decades in furniture and linen, that it waits patiently in rooms, cellars and that perhaps the day would come when the plague, for the misfortune and instruction of human beings, would awaken its rats and send them to die in a happy city.”5

As the shadow of Nazi rule spread across Europe, Jacques let himself be guided by his inner light and, at the age of sixteen, became the leader of the network Les Volontaires de la Liberté (Volunteers of Freedom), which he’d founded. “Nazism is not a historical evil confined to a particular time and place as a German evil. Nazism is a ubiquitous seed, an endemic disease of humanity. It’s enough to throw a few bouquets of fear to the wind to reap a harvest of betrayal and torture in the coming season,” wrote Lusseyran, as quoted by the mayor of Trappes 66 years after the first meetings of the Volunteers of Liberty in the Paris apartment of the Lusseyran family.6

Subsequently, Jacques Lusseyran joined the Défense de la France (Defense of France) movement and soon became a member of the Executive Board of the newspaper of the same name, whose distribution he supported with his “troops” of volunteers. Under the pseudonym “Vindex,” he wrote the editorial of July 14, 1943, which he concluded with the following words: “By defending France, we also defend the human person and his freedom to choose and dare. It must be possible more than ever to say today, as it was written on a sign at the bridge of Kehl in 1790: This is where the land of freedom begins.”7

Betrayed by a young volunteer whose unreliability he had only just suspected, Jacques suffered the hell of prison and the Buchenwald concentration camp. He then returned as a survivor among the living, filled with the experience of his encounter with Christ, which he’d experienced in the depths of his being during this suffering and deprivation of humanity.

Seeking Meaning in the Light

Jacques Lusseyran and Albert Camus believed fundamentally in the human being and in their ability to embrace freedom. They were “thinkers of light.” Lusseyran’s light is an inward, inexhaustible source of life and meaning: “Light does not come from outside. It’s within us, even without eyes.”8 Jacques Lusseyran was working on a dissertation on Nerval’s poem, “The Black Sun of Melancholy,” during the time in which Camus wrote: “At certain times, the landscape is black with sun.”9 Camus’ light can dazzle because it holds so much shadow: “The light splashed onto the steel and it was like a long, sparkling blade that reached my forehead. At that same moment, the sweat that had collected in my eyebrows ran down my eyelids and covered them with a warm, thick veil. My eyes were blinded by this curtain of salt and tears.”10 Meursault, the main character in Camus’ novel The Stranger, loses contact with himself and knocks “four short blows on the door of misfortune.” By opening this door, he leaves the realm of absurd indifference and comes into contact with himself. As in echo, Jacques Lusseyran described how his perception of light depended upon his inner state: “The actual changes depended on my psychological state. When I was sad, when I was afraid, all the colors became dark and all the shapes unclear. On the other hand, when I was happy and attentive, all the images became bright. Resentment and scruples made everything black. A generous intention, a courageous decision cast a huge light. More and more, I came to reason that to love is to see, and to hate is to be blinded and to live in darkness.”11

Both felt alive in the light, connected to the place where the self is so deep that it dissolves its ego and becomes a self that connects every human being to every other in the source that unites them. They sang a hymn to the light that was also a hymn to the spirit. Both were tireless in their search for meaning, fulfillment, and happiness, which they also sought in love.

“Oh yes, he had loved her with a great love, with all his heart and his body too, yes, with her it was a fervent desire, and when he withdrew from her with a great silent cry at the moment of orgasm, he was in passionate harmony with his world.”12 Who is Camus talking about in the last pages of The First Man? Marie Casarès, the great love of his life, or another woman among all those to whom he was always both faithful and unfaithful at the same time because he loved them all so much? In any case, it was Marie to whom he wrote: “Marie—with love one doesn’t conquer another but oneself,”13 which underlines the dimension of the ‘I’ so present in Lusseyran’s last book, Conversation amoureuse [Amorous conversation], when he speaks to his third wife Marie, whom he met in the United States: “Love is only instinctive at its root; everywhere else it’s adventure. Love is the greatest endeavor for change that human beings have known to this day. . . . It’s the unique moment when consciousness and life, these two enemies, find the power to take a few steps together.”14 These sensual and spiritual experiences of love point to other intimate driving forces in their approaches to life.

Beyond Death

On January 4, 1960, the unfinished manuscript of The First Man was found in Camus’ pocket. It ends as follows: “he, like a solitary and ever-shining blade of a sword, was destined to be shattered with a single blow and forever, an unalloyed passion for life confronting utter death; today he felt life, youth, people slipping away from him, without being able to hold on to any of them, left with the blind hope that this obscure force that for so many years had raised him above the daily routine, nourished him unstintingly, and been equal to the most difficult circumstances—that, as it had with endless generosity given him reason to live, it would also give him reason to grow old and die without rebellion.”15

The last lines of Jacques Lusseyran’s article “La mort devient la vie” [Death becomes life], describing his experiences in Buchenwald, seem like an echo of this premonition of death: “Then one day, it seemed to me, as if someone were speaking to me. It was right above me. There was a thick curtain that moved. The voice was uncertain and very fast. Someone inside me knew the voice, but not all of me. I was told that I was going to die, that people were thinking of me, and that they loved me very much. I was also told not to be unhappy. It was probably a friend who spoke. I wasn’t surprised, because I wasn’t interested. I didn’t even think of answering. I only tried to move away from the voice, look at it smiling, and say in my heart: ‘But I’m happy!’ Then the news of my death went its way and met my consciousness, which would not admit it. Dying was a word it did not know, simply a word, whose meaning seemed improbable and completely useless to it. It saw only life in and around itself.”16

Jacques Lusseyran and Albert Camus, paradoxical beings woven of light and shadow, passion and reason, died in the midst of life, in their prime, leaving behind inexhaustible treasures for generations to come, which shine in the souls of those who read them, live them, and engage in dialogue with them beyond death.

Albert Camus had two children, twins whom he loved but sometimes referred to with tender irony as “obstacles.” Catherine, his daughter, patiently took up the manuscripts of the text that was published in 1994 under the title The First Man. She continues to work tirelessly to keep her father’s memory alive. Jacques Lusseyran had four children by two different women. As he himself admitted, he was never really able to reconcile his life with his responsibility as a father. It’s thanks to his eldest daughter Claire, whom the biographer Jérôme Garcin praised for her “exemplary loyalty to the memory of her father”17, that we can get in touch with this being through the work he left behind. Did both of them understand that their fathers belonged to the world of the future, at least as much as to their own, somewhat neglected childhood? And that, as Christian Bobin writes, “there are times when the bond between two human beings is so strong that it continues to live even when one of the two can no longer see it”?18

This is the secret of “elective affinities”: it enables this inner dialogue, from which new thoughts arise again and again to question life. The touching vulnerability of these two human beings encourages us to face the storms of the future in order to create a new present every day. Both have understood how to live from their deepest selves despite but also with the shadows cast by their great lights. They remain beacons in these challenging times, which demand that each of us develop our own individual ethics, or, as Rudolf Steiner calls it in his Philosophy of Freedom, an ethical individualism.

Translation from French to German Louis Defèche

Translation from German to English Joshua Kelberman

Title image Jacques Lusseyran with his wife Jacqueline Pardon and Albert Camus in Angers in 1953 © DR.

Footnotes

- Albert Camus, Notebooks, 1935–1942, vol. 1 (Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, 2010).

- Quote from Olivier Todd, Albert Camus: A Life (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1998).

- Albert Camus, “Editorial,” Combat (August 8, 1945).

- Albert Camus, The Rebel (New York: Vintage, 1992); first published in French, 1951.

- Albert Camus, The Plague (New York: Knopf, 2021); first published in French, 1947.

- Ali Rabeh, Mayor of Trappes, on the occasion of the National Day of Remembrance for the victims and heroes of the deportation on April 25, 2021.

- Vindex (Jacques Lusseyran), “Editorial,” Défense de la France (July 14, 1943).

- Jacques Lusseyran, And There Was Light (Edinburgh, UK: Floris, 1985); first published in French in 1953.

- Albert Camus, “Nuptials at Tipasa” in Nuptials, included in Lyrical and Critical Essays (New York: Vintage, 1970); first published in French in 1938.

- Albert Camus, The Stranger (New York: Penguin, 2012); first published in French in 1942.

- Jacques Lusseyran, La lumière dans les ténèbres [Light in the darkness] (Paris: Éditions Triades, 2002).

- Albert Camus, The First Man, translated by David Hapgood (New York: Knopf, 1995); first published posthumously in French in 1994.

- Albert Camus, Letters 1944–1959 (New York: Penguin, 2026), forthcoming.

- Jacques Lusseyran, Conversation amoureuse (Fair Oaks, CA: Rudolf Steiner College, 2018); first published in French in 1990.

- See footnote 12.

- See footnote 11.

- Jérôme Garcin, Le voyant [The seer] (Paris: Folio, 2016).

- Christian Bobin, Ressusciter [Resurrecting] (Gallimard, 2001).