It’s not easy to put the essence of anthroposophy into words. How can one explain to skeptics, for example, what anthroposophy’s significance is for today’s humanity and for the future? Wolfgang Müller undertakes this task with his new book Das Rätsel Rudolf Steiner [The riddle of Rudolf Steiner], published by Kröner for the hundredth anniversary of Rudolf Steiner’s death. Below is a passage from the end of his book.

In the future world, everything is as it was in the previous world—and yet, everything is completely different. — Novalis1

What would be different if anthroposophy had a wider broadcast? If it were not only known through its practical fields like Waldorf schools, but if its central messages were heard and anthroposophy became a “cultural factor,” as Rudolf Steiner hoped a hundred years ago?

This would probably be a rather quiet change, something almost imperceptible that could not be easily defined and conceptualized. After all, it’s not as if anthroposophy is shouting at modern civilization, “Everything is wrong, everything must change!” Instead, anthroposophy understands that human development essentially had to go in this direction, that the sober-materialistic profile of our age has its meaning and significance. Anthroposophy simply adds to this: now a new step is necessary, a first step, and anthroposophy would like to contribute to this.

In other words, anthroposophy doesn’t show a different world from the usual one. It shows this world in a new light, with different lighting, so to speak, so that aspects emerge that weren’t visible before. And anthroposophy also shows things from new perspectives, so that things come into view that were hidden before. So, from this perspective, one can indeed speak of a major, fundamental transformation that changes everything. Rudolf Steiner once said: “Anthroposophy teaches you to look at every plant and every stone differently than you looked at a plant or stone before.”2

Not Teaching Material, but an “Elixir of Life”

This is also what those who live with anthroposophy feel. Things take on a different color; the world exhibits itself in a richer and more interesting way that’s difficult to fully describe. We haven’t at all forgotten what we thought and knew previously; but, now in retrospect, it all seems rather narrow and sparse, and we don’t want to go back. Not because we now have a new store of knowledge, great truths about the world around us and higher worlds, too, but because we now stand in the world differently, younger somehow, more curious. Steiner wanted anthroposophy to be understood in this sense: not as a system or as “teaching material,” but as an impulse for development; not something finished, but a seed for something new. “Become geniuses at having interest!”3 he called out to his listeners in a speech to young people. He didn’t consider this open, receptive, enthusiastic attitude to be a thing or a privilege of the youth, but a theme for the whole of life, meaning that we keep ourselves inwardly pliant, flexible, ready for new things, active. Steiner repeatedly spoke of the fact that in earlier humanity many processes still took place naturally, semi-consciously, instinctively. But now this is becoming less and less sustainable. In our age, we must take our development into our own hands more and more. Today, everything essential must be “acquired consciously”:

In the future, what we build up out of our inherited dispositions will only last until we’re 27 years old at the most, and farther in the future it will always be a younger and younger age. You know this from our earlier observations. We need something that will sustain us throughout our lives as a human being that is in a process of becoming; not one that simply is, not a concluded, finished human being.4

One of the basic concerns of anthroposophy is to point to what makes people inwardly mobile and keeps them mobile. Steiner even once spoke of an “elixir of life.”5 If we bypass these ever-fresh sources of life, everything becomes dried-up intellectuality. We stop with what we acquired and mentally assimilated in the first third of our lives, and we’re not inwardly prepared to allow anything more than small additions. (From this viewpoint, it can sometimes seem as if we’re surrounded by a bunch of gray-haired twenty-somethings). This backward-looking attitude, with a tendency for mental repetition, blocks access to anthroposophy because whenever someone with this view meets something, they only see what they already know:

Just look how satisfied someone is when they come to something in one of my lectures about which they can say: look, that’s also in an old book. But it’s written completely differently, even out of wholly different foundations of consciousness! One is so lacking in the courage to accept what’s growing in the present-day soil that one feels reassured when one can bring something like this from the past.6

Above all, such an attitude blocks an open, explorative, lively relationship to the world, one that’s interested in the present—certainly, the simplest and most difficult thing of all (something that old Zen masters knew and can be conquered today under completely different conditions). Of course, this opportunity is also missed by those from the anthroposophical milieu who present themselves as so all-knowing that the true present and its true counterparts don’t stand a chance against their version of a ready-made worldview. This is anthroposophy turned into its opposite. Anthroposophy’s central impulse goes in the other direction: it wants to encourage a free, unbiased, empathetic approach to the world. “Let us approach everything that surrounds us with the feeling that every fact can tell us something special,”7 says Rudolf Steiner. This does not mean eliminating experience and previous knowledge; but it does mean not allowing the past to obscure our view of the present, not drifting into a stale pseudo-realism that has no eye for the fact that “basically, not a day goes by in which a miracle does not occur in our lives.”8 This is the charming side, the “magic breath”9 of anthroposophy. But there is another side.

Paths to a More Substantial Science

This other side has to do with the fact that such an attitude is difficult to achieve and difficult to maintain because the whole of modern civilization puts up a strong resistance. Modern civilization moves in completely different mental patterns that hardly leave any access to the viewpoints of anthroposophy. And its clear that even those who sense these biases and can see through them to some extent are still children of their time, shaped by their barely conscious preconceptions and biases. In short, we’re dealing here with tough, protracted processes that first need to be set in motion.

The first process is a kind of necessary destruction, a shattering of the prevailing ways of thinking. Mainstream ideas suggest that modern science has reached unprecedented heights and is well on the way to an ever more complete understanding of the world. Admittedly, there are gaps that need clarification in some details, but overall (according to the commonly held view) everything is going in the right direction. From this supposed superior position, some kind of fundamental rethink or even consideration of other perspectives (like those in anthroposophy) is not recognized as a need. So, anthroposophy is dismissed (if it’s perceived at all) as unscientific and irrational, and as something unnecessary, even annoying.

Standing up against this arrogance with steadfastness and intelligence is no small task. It is a major, revolutionary challenge. And it can only succeed if one’s own point of view is clarified as thoroughly as possible, and the deficits and one-sidedness of today’s science are exposed in a reasonable way. One starting point could be: the inability of modern science to develop a convincing picture of the human being—not just to grasp aspects of the human being that are scientifically ascertainable (for instance, how humans are like animals), but to focus on what is specifically human. A science fixated on verifiability in the laboratory is only able to recognize a weak imitation of what it means to be human.

What this modern worldview of science is able to grasp can be characterized with the following example. Suppose we analyze Leonardo’s Mona Lisa with purely scientific means. We then conclude that different color pigments have been applied to a board of poplar wood. Our result is completely accurate, but unfortunately doesn’t come close to what’s understood and experienced by a human encounter with this work of art. In other words, we need to show how miserably this kind of science fails as soon as it addresses more complex but essential questions, how it remains on the surface of things, and how much this central weakness is constantly obscured by a glut of details concerning secondary questions (which pigments, where were they obtained, how were they processed, etc.). Only then can it become clear that today’s dominant understanding of the world does need to be expanded after all.

Bringing this to light is not an anti-scientific attitude. On the contrary, it opens the way to a better, more substantive, more thorough, more comprehensive science. What such a scientific and ideological expansion looks like in detail—and what anthroposophy has to contribute to it—is a subject for extensive discussions. But when the need for expansion is not even admitted, when we deny and ignore the limits and blind spots of today’s dominant approach to the world, we actually prove our intellectual impoverishment.

That notwithstanding, this view of science is still basically the current standard of world culture. The lack of interest in expanding one’s worldview is evidence enough: look at how ignored anthroposophy usually is, or, when it is given attention, how it’s usually met with impudence and mockery. Rudolf Steiner understood there was a lot in store for this “little group” of anthroposophists who held the conviction that here was something significant that needed to be communicated to the world: “Let people laugh at us and let them say that it’s presumptuous to believe this; it’s still true.”10

The Mystery that Anthroposophy Points To

But—and this is also part of the picture—this self-awareness must be underpinned by the capacity already mentioned: to formulate a convincing criticism of today’s dominant cultural paradigms. Only then can it become clear that this criticism doesn’t come from a sentimental resistance to modernity but rather from a consciousness of the blockades set in place in our time and of viable paths to a better future. The anthroposophical movement has not yet developed this force and clarity. In fact, what Steiner said in 1917 still applies: this current “cannot yet find those who would be capable of creating an aura of being taken seriously, so to speak.”11

Rudolf Steiner probably held it to be an open question whether humanity would consciously take hold of and create what’s needed or whether it would—apathetically, arrogantly, and thoughtlessly—miss the opportunity. In such contexts, he occasionally said: then, karma will prevail—which probably means: then things will proceed in their unconscious, lawful way, until perhaps an awakening will come out of the depths of catastrophe, a moment of freedom, and conscious decision. Either way, Steiner saw only one single, always realizable requirement guiding the behavior of the individual human being: to take it seriously, to the very depths, “that dispositions, thoughts, namely impulses of consciousness are realities”—realities that ultimately do not become effective through external means but in much deeper ways. One will then be certain “that what one draws from such impulses will reach its correct goal despite all externally apparent failure . . . .”12

This goal could present itself as a summation, a mature fruit of human history, as a synthesis of all that has been unfolded from various fascinating one-sided viewpoints. From the ancient religious and mystical attempts to fathom the world’s inner realms, the heart of being, to the brilliant, precise modern natural science that approaches the very same world in a very different way—everything could then come together to form a coherent, richly nuanced picture in which human and world are, so to speak, felt and illuminated from deep within all the way out to the very ends. Anthroposophy, with its eminent sense for the justification of different viewpoints and ways of knowing, would be nothing other than a midwife of mental integration. However, with the uncomfortable emphasis that this integration presupposes, above all else, a departure that has to be made within us as human beings ourselves—a developmental step and change of direction that makes us capable of knowledge in this more comprehensive sense in the first place.

Perhaps this is the Mystery anthroposophy points to: that human beings don’t find and recognize the deeper picture of the world as something already given, but that it only comes into being through us in the fullest sense; that human beings therefore have something to complete here without which the world would remain a fragment. And perhaps the one secret also includes a second one: that humanity had to walk these long paths, upon which the world appeared increasingly strange and cold, until everything can finally turn and reshape itself spiritually, and thereby achieve a new intimacy and closeness with itself. Home would then be something that lies behind us—and in front.

From Wolfgang Müller, Das Rätsel Rudolf Steiner. Irritation und Inspiration [The riddle of Rudolf Steiner. Irritation and inspiration] (Stuttgart: Kröner Verlag, 2025).

Translation Joshua Kelberman

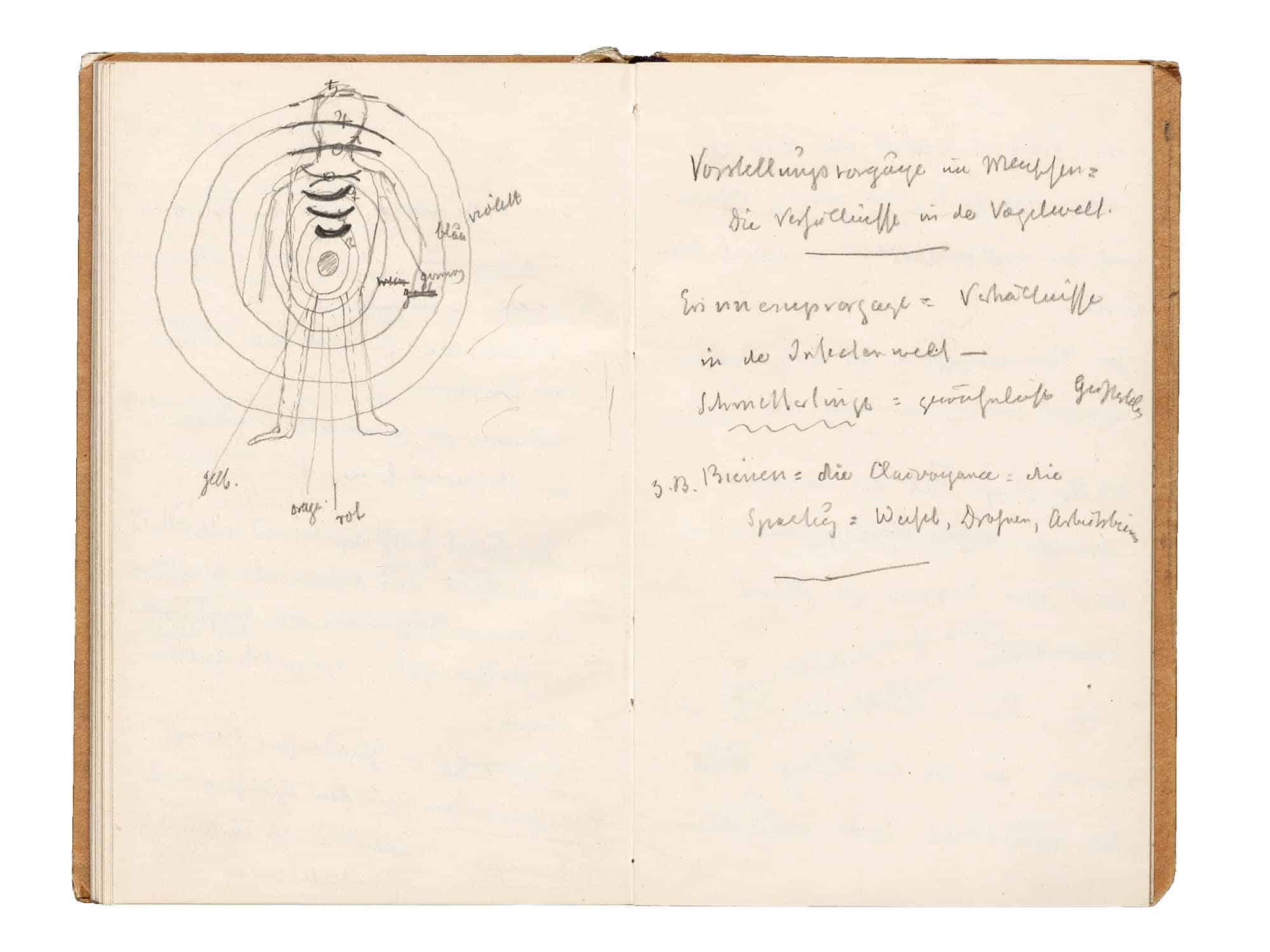

Title image Rudolf Steiner, Notebook 86, pp. 78-79:

“Imagination processes in the human being:

The relationships in the world of birds.

Memory processes = relationships in the insect world -︎

Butterflies = ordinary mental life

eg. Bees = the clairvoyance = the division = queen bees, drones, worker bees”

Footnotes

- Novalis, Werke [Works] (Munich: Beck 2001), p. 455.

- Rudolf Steiner, Michaelmas and the Soul-Forces of Man, CW 223 (Spring Valley, NY: Anthroposophic Press, 1982), lecture in Vienna on Sept. 28, 1923.

- Rudolf Steiner, Youth and the Etheric Heart: Rudolf Steiner Speaks to the Younger Generation, CW 217a (Hudson, NY: SteinerBooks, 2007), address given in Stuttgart, Feb. 8, 1923.

- Rudolf Steiner, The Challenge of the Times, CW 186 (Spring Valley, NY: Anthroposophic Press, 1979), lecture in Dornach on Dec. 8, 1918.

- Rudolf Steiner, The Fruits of Anthroposophy, CW 78 (London: Rudolf Steiner Press, 1986), lecture in Stuttgart on Sept. 6, 1921.

- Rudolf Steiner, Karmic Relationships: Esoteric Studies. Vol. 3., CW 237 (Forest Row, East Sussex: Rudolf Steiner Press, 2002, repr.), lecture in Dornach on July 4, 1924.

- Rudolf Steiner, Wo und wie findet man den Geist? [Where and how does one find the spirit?], GA 57, 2nd edn. (Basel: Rudolf Steiner Verlag, 1984), lecture in Berlin on Feb. 11, 1909; cf. Rudolf Steiner, “Practical Training in Thought,” in Anthroposophy in Everyday Life (USA: Anthroposophic Press, 1995), lecture in Karlsruhe on Jan. 18, 1909.

- Rudolf Steiner, Death as Metamorphosis of Life, CW 182 (Great Barrington, MA: SteinerBooks, 2008), lecture in Zurich on Oct. 9, 1918.

- Rudolf Steiner, Europe Between East and West: In Cosmic and Human History, CW 174a (Forest Row, East Sussex: Rudolf Steiner Press, 2024), lecture in Munich on Dec. 3, 1914.

- Rudolf Steiner, Education as a Force for Social Change, CW 296 (Hudson, NY: Anthroposophic Press, 1997), lecture in Dornach on Aug. 17, 1919.

- Rudolf Steiner, Zeitgeschichtliche Betrachtungen [Reflections on contemporary history], vol. 3, CW 173c (Basel: Rudolf Steiner Verlag, 2010), p. 235.

- Rudolf Steiner, Das Schicksalsjahr 1923 in der Geschichte der Anthroposophischen Gesellschaft [1923: The year of destiny in the history of the Anthroposophical Society], GA 259 (Basel: Rudolf Steiner Verlag, 1991), address given in Dornach on June 17, 1923.

another book worth reading .. how and were to get it ?

The book is available in German and published by the Kröner Verlag. You can order it directly at there website: https://www.kroener-verlag.de/books/das-r%C3%A4tsel-rudolf-steiner.html