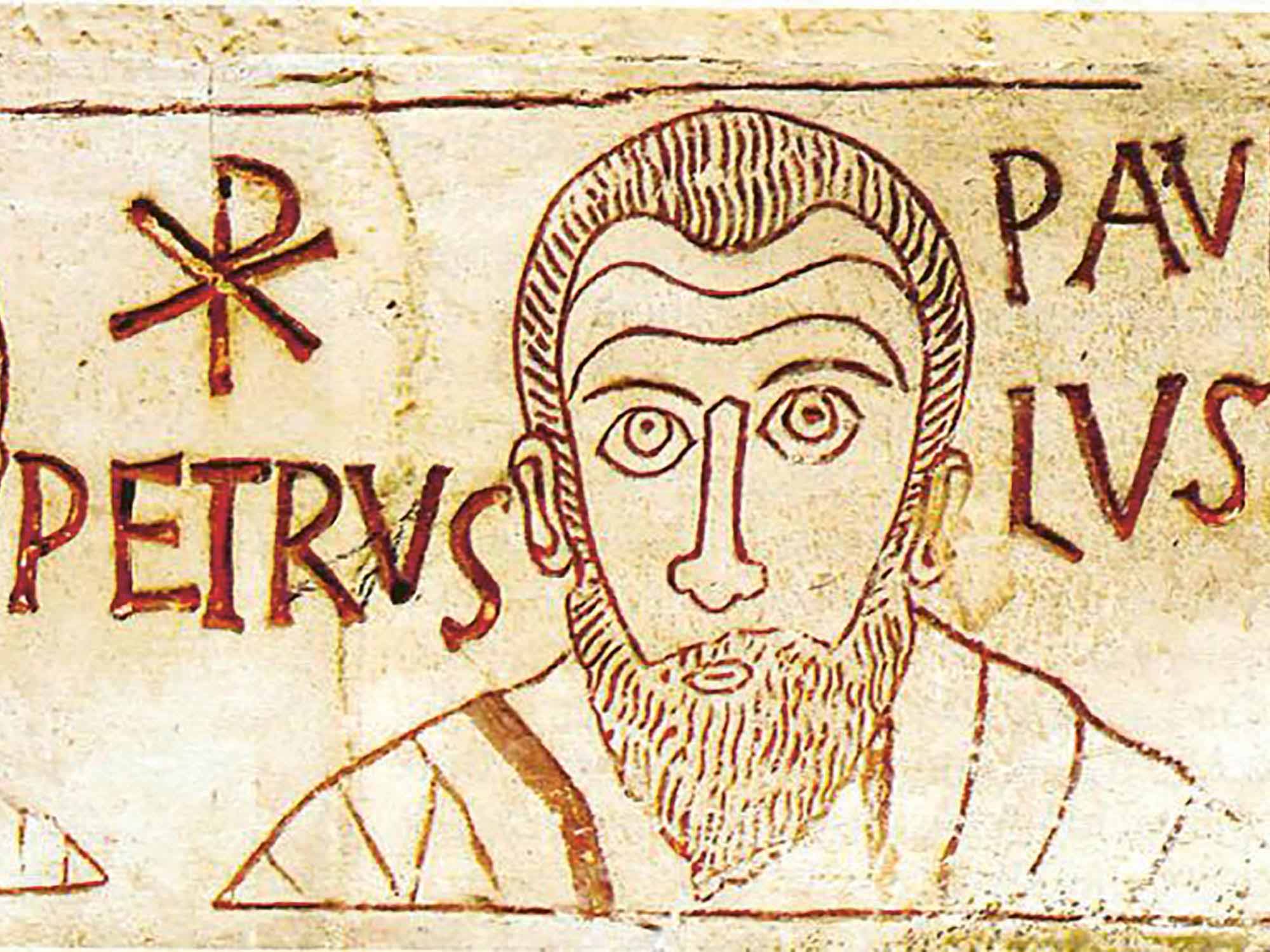

The thinking of Paul of Tarsus has come down to us in his letters written in ancient Greek. To understand them in depth, one must go back to this original source. Olivier Coutris has done this, revealing the first philosophy of freedom in Christian history. This sophisticated philosophy of freedom, based on individualized thinking freed from conformism, leads to a consciousness of humanity that can transcend all affiliations and religions.

“Do not be conformed to this world, but be transformed by the renewing of your minds, so that you may discern what is the will of God—what is good and acceptable and perfect.” (Romans 12:2). Thus Paul speaks to the Romans. This verse is a marvel of brevity and a true philosophical compendium. The Greek verb suskhēmatízō, “to conform,” contains the concept of being subject to a scheme (skhē̃ma). Paul therefore calls on the Romans to not submit to the prevailing schemes of their time.

Renewal of the Intelligence

The inner transformation or metamorphosis (metămórphōsĭs) that Paul encouraged consisted of a renewal of the intelligence. The word anakaínōsis (renewal), which is composed of the prefix ana-,1 indicating a reversal upwards, to the origin, to the spiritual, and kainós, indicating the new, literally meant “to be new again in one’s consciousness.” Here, we find an echo of the idea of “emptiness” taught by Buddhism or, more recently, for example, by Krishnamurti (1895–1986). It also refers to Rudolf Steiner’s central idea of “pure thinking.”

This renewal concerns noũs, the intelligence—not the intellectual capacity as we understand it today, but the intelligence that connects the individual with the spirit. From the moment a human being is born in a place and time, he or she is shaped by a culture, a religion, a scientific or a political way of thinking. Overcoming these innate prejudices is the first step towards individual realization. The second step is to rise above the personal sphere in order to achieve the objectivity of intelligence (noũs), through which the individual fits into the unified world. Vladimir Vernadsky (1863–1945) understood the “noosphere” as the communal spiritual sphere of all humanity. Nevertheless, this spiritual community of humanity is the opposite of conformity or “unitary thinking.”

Whoever wants to escape conformity must start by working with language. This is a truly Johannine task, for according to John, “In the beginning was the Word,” the lógos—a Greek concept that arose from the Indo-European root *leǵ-, which expressed the essence of connectedness. It can be found in “religion,” “legality,” “lecture,” lesen, (German, to read). In the beginning, there was a connection between everything, in the beginning there was unity, an active unity. Steiner thus suggested that the meaning of words should be returned to, re-learned, and re-understand, and he placed special emphasis on the developmental capacity of the world and knowledge about the world: “The attainment of knowledge does not merely rest upon the fact that one learns to talk more about something in the way other people talk about it, and in just the same way they do; rather, it’s really the acquisition of another piece of the world.”2

Free Yourself From Automatism

In the Middle Ages, the Seven Liberal Arts were practiced in order to liberate the soul. The illustrious School of Chartres invited its students to begin by purifying their souls to be able to approach concepts in a healthy way. The first of the liberal arts, grammar, consisted of discovering what words meant and how to organize them in order to express oneself. “Grammar” comes from the Greek grámma, which refers to any unit of communication, from letters used to write words to musical notes to a unit of weight used to exchange materials. Grammar was the basis of communication. By practicing it, the students freed themselves from the traditional barriers to communication and learned to understand one another. Paul’s letters are a foretaste of this art owing to their high semantic content.

“One who thinks they know something, doesn’t yet know as one should know.” (1 Corinthians 8:2, rev. by the author). These words sound like a Buddha sutra or a Japanese koan. Paul knew that the path of knowledge—the inner path—is fraught with pitfalls. What we believe we know results from our conditioning and, secondly, from our limited senses, which are therefore sources of illusion. Untrained knowledge is essentially based on automation. Few human beings master the creation of their thoughts and perceptions. A child is born with infinite potential. They can, for example, learn any language in the world, as they are still universal, filled with unimaginable wisdom. Through incarnation, they emerge from universality to become part of humanity as an individual. Regaining true knowledge is, in a way, a second birth; thus, we can say with Paul: to know (French, connaître, co- + naître, to be born together with) is to regain in consciousness the universality from which all being emerges.

Steiner thus comments on Paul’s words to the Corinthians: “A human being doesn’t see truth when he looks out with his eyes; he doesn’t see reality when he looks into what is outside. Why not? Because, in his descent into matter, he, himself, has transfused external reality into illusion! It is the human being himself who has turned the outer world into an illusion by his deed!”3 The world, as seen through the filter of the senses, is, indeed, an illusion inherent in the fact that one is embodied. But human beings can free themselves from their filters and develop suprasensible capacities. It’s not the world that’s an illusion, but rather just the way and manner in which human beings perceive it. Human beings create their own illusions by perceiving the world only with their ordinary senses.

Consciousness as Source

Paul was the first Christian author to speak of “consciousness,” but also one of the first to deal with the development of human consciousness. In his letters, the words súnesis4 and sŭneídēsĭs5 occur in nearly thirty places. These words can be translated as “conscience” or “consciousness.” In the following, we will choose the wording “consciousness.”

In conjunction with the verb sŭnī́ēmĭ, meaning “to bring together by thought,” the concept sŭ́nesĭs expresses the movement at work in the process of consciousness. Philosophically, the second concept, sŭneídēsĭs (sŭn- + eídō), was stronger and mirrored what consciousness itself was. In Greek, sŭn- was an associative prefix. And the verb eídō meant “to see” and “to grasp.” Related to this verb, the noun idéā denoted both a spiritual idea and a form in the material world. For example, when Plato (428–348 BC) spoke of a dodecahedron, he saw not only the form but also the idea through the form. At that time, seeing and comprehending were one and the same. Over time, certain human capacities became weaker. The Greek verb eídō, which became videō in Latin, lost its spiritual dimension and only expressed the sensible aspect of seeing.

The concept of “consciousness” (sŭneídēsĭs) was coined by Greek philosophers in Asia Minor around 700 BC. It remained limited to philosophy until Paul used it to talk about God. For the first time in the history of humanity, a human being approached the spiritual world through his consciousness, through his individual consciousness! Two thousand years later, this bold invention has still not really arrived.

It’s assumed that Paul wrote his letters in the years 50 to 67, before Mark, Luke, Matthew, and John had written their gospels. He was, therefore, the first Christian author, which is usually forgotten. The question, therefore, arises: Where did Paul get his inspiration if he hadn’t read the Gospels, which didn’t exist yet, and since he hadn’t been an eyewitness to Jesus Christ? The answer lies in one word: sŭneídēsĭs, consciousness! On the road to Damascus, during his suprasensible encounter with Christ, Paul had the shattering experience of absolute consciousness. From that moment on, he spared no effort to incorporate the philosophical concept of consciousness into a completely new approach to the divine world.

For Paul, there is no opposition between science and religion. If science and religion are associated with the two faculties of knowledge and belief, which are regarded as opposites, does not the opposition stem from the way in which knowledge and belief are understood? And what place does consciousness occupy in this context? Steiner laid down a similarly surprising and Pauline principle: “In religious feeling one acquires the consciousness of the spirit, and in the science of the spirit one acquires the knowledge of the spirit.”6

The Law of the Heart

The Decalogue—ten dictums of Yahweh handed down by Moses—appeared at a time when human beings did not yet have the full possibility of grasping themselves in their ‘I.’ The event of Golgotha changed this in that the archetype of consciousness—the “I am,” known as “Christ”—became accessible to every human being. This did not escape Paul: “When pagans, who do not possess the Law, do instinctively what the Law requires, these, though not having the Law, are themselves the Law. They show that what the Law requires is written on their hearts, to which their own conscience also bears witness; and their conflicting thoughts will accuse or perhaps excuse them” (Romans 2:14–15, rev. by author).

With an unrelenting logic, Paul was essentially saying: when someone adopts a behavior of their own accord, without being prompted to do so from the outside, this shows that “something” is at work within them. Furthermore, when they are conscious of what is “working in them,” then they no longer need the Law. Paul presented these ideas to the teachers of the Law! Since he had been a fanatical Pharisee, he knew exactly what the Law was and how dangerous it was for anyone who dared to contradict it.7 Hadn’t he ordered the stoning of Stephen?8 Only his consciousness gave him the courage in the Jewish environment to dare to suggest giving up the Law.

According to Paul, the Hebrew law aimed to develop the individual self, for which it was a kind of pedagogue. Paidăgōgós literally meant “the one who guides the child,” as long as the child is not able to guide himself. This is why Paul writes: “Now before faith came, we were imprisoned and guarded under the Law until faith would be revealed. Therefore, the Law was our pedagogue (paidagōgòs) until Christ came, so that we might be justified by faith. But faith having come, we are no longer under the dependence of the Law” (Galatians 3:23–25, rev. by the author). Paradoxically, the meanderings of evolution led to the great Christian churches also adopting the attitude of a pedagogue and preserving the law. But St. Paul, by asserting that everyone who comes to his own self is himself the law, was already anticipating a philosophy of freedom, an ethical individualism, which was later formulated by the German idealists and then by Steiner.

Necessity of Heresies

Paul, like anthroposophy, placed great emphasis on the social significance of his teaching. As the first architect of Christianity, he founded communities, which he called ekklēsía.9 This concept became ecclēsia in Latin, église (church) in French, [and ecclesiastic in English]. Naturally, there was no church in Paul’s time, neither Catholic, Protestant, nor Orthodox! It is unfortunate that ekklēsía has been translated as “church,” as this word brings certain modern connotations. What was the meaning of ekklēsía in Paul’s time? The word, which was formed from the prefix ek- and the noun klēsis, indicated an “assembly summoned together.” The concept, which was adopted by various religious denominations, originally had a universal meaning. Spectators who gathered in a hall to listen to a concert that had been announced also formed an ekklēsía. In addition, some languages also use the word église (church) for the walls within which a religious community gathers.

Two words would be appropriate to translate ekklēsía without denominational connotation. “Community” (Lat. commūnitās) can be used, which expresses a shared (com-) responsibility (mūnis). One can also translate ekklēsía as “assembly,” based on the Indo-European root *sem-, “together; one” expressing identity; also, in connection with Shem, the son of Noah, who was to “bear the name.” The Semitic peoples, the heirs of Shem, had to especially develop the ‘I’, the name. The translation to “assembly” points to a plurality of individuals.

Was Paul uncompromising in his doctrine, as is often claimed? His letter to the Corinthians casts doubt upon this: “For, to begin with, when you come together as an assembly, I hear that there are divisions (skhĭ́sma) among you; and to some extent I believe it. Indeed, there have to be free choices (haíresĭs) among you, for only so will it become clear who among you are genuine” (1 Corinthians 11:18–19, rev. by author). Paul reminded the Corinthians that it was not astonishing that there should be discord, skhĭ́smă, schisms, in an assembly of human beings, since it was essential for him that everyone should have a free choice, an haíresĭs. It is a linguistic irony that the word haíresĭs, transliterated into “heresy,” became, in the eyes of the Church, a vice to be eradicated. The fight against heresy is an attack on freedom of choice.

The Pedagogy of Spiritual Science

Paul’s social concern was based on pedagogical qualities: “Those who speak in tongues build themselves up, but those who prophesy build up the community (ekklēsía). Now, I would like all of you to speak in tongues but even more to prophesy. One who prophesies is greater than one who speaks in tongues, unless someone interprets, so that the community may be built up. Now, brothers and sisters, if I come to you speaking in tongues, how will I benefit you unless I speak to you in some revelation or knowledge or prophecy or teaching?” (1 Corinthians 14:4–6, rev. by author).

What did he mean by oikodomē (edification)? The Greeks considered the house (oĩkos) to be the basic spatial cell of human beings. For this reason, many words are constructed from oĩkos, such as ecology, economy, diocese, metic (métoĩkos), etc. The house was the unit of life, just as grámma was the unit of communication. Therefore, edification, oikodomē, the building of a house, was a highly significant concept for Paul.

What Paul calls “speaking in tongues” means speaking in a language that is considered heavenly or inspired but is unknown or incomprehensible to the listeners. However, it was important to him that the speech was edifying. Ă̓pokắlŭpsĭsis is composed of the prefix apo- (concept of eviction) and kắlŭx (calyx).10 The original meaning of “apocalypse” was unveiling or revelation, i.e. the removal of a veil that conceals something. Paul wanted spiritual truth to be revealed, thereby making it useful for the assembly. Speech, he added, should bring gnō̃sĭs (knowledge as defined above, not as a quantity of something known), as well as “prophecy” and “teaching.” While today, a prophecy (prophēteíā) has a rather pejorative, divinatory undertone, it had a very different meaning for Paul. The verb prophēteúō, expressing one’s thoughts through words (verb phēmí) in advance (pro-), meant “to interpret the divine word,” i.e., to explain spiritual realities that would otherwise remain inaccessible to ordinary mortals. Paul thus attributed these four basic properties to all edifying speech: ă̓pokắlŭpsĭsis (unveiling), gnō̃sĭs (knowledge), prophēteíā (prophecy), dĭdăkhḗ (teaching). He believed it was better to remain silent than to speak without these four qualities.

Steiner had a similar pedagogical concern: “It is uncomfortable for people to admit that the spiritual should really be seen and understood. . . . Now, all spiritual science consists in the fact that the mystery is unveiled, that the mystery really steps out before the world.”11 He uses the verb “unveil” (enthüllen) here in the sense that Paul and John used it.

For the Whole of Humanity

Neither Paul nor anthroposophy regard Christianity as a religious creed. The turning point of Golgotha is a fact common to all humanity, like the continental drift. It shouldn’t be equated with the emergence of a new religion.

Paul announces to the Colossians that he is to reveal “the mystery hidden for eons and generations but now revealed to his saints. To them, God chose to make known how great among the pagans are the riches of the glory of this mystery, which is Christ in you, the hope of glory” (Colossians 1:26–28, rev. by author). The Mystery of Christ that was revealed to Paul made it possible for him to emphasize the universality of human nature. Transcending all denominational, social, and ethnic boundaries, he wrote to the Galatians: “There is no longer Jew or Greek, there is no longer slave or free, there is no longer male and female; for all of you are one in Christ Jesus” (Galatians 3:28).

Echoing the Pauline message, Steiner also emphasized the universality and timelessness of Christ: “The true understanding of anyone who professes the Christ rests on the fact that he becomes conscious that the Christ impulse is not limited to one part of the Earth—this would be an error. The reality is that since the Mystery of Golgotha, what Paul already said for the areas for which he had to speak, is really true. Paul proclaimed: Christ died for the pagans too. But, humanity must understand that Christ came, not for a particular people, for a particular, limited time, but for the entire population of the Earth, for all.”12

Freedom Nourishes the Community

“Now, before faith came, we were imprisoned and guarded under the Law until faith would be revealed. Therefore the Law was our pedagogue (paidagōgòs) until Christ came, so that we might be justified by faith. But now that faith has come, we are no longer subject to a pedagogue” (Galatians 3:23–25, rev. by author). Paul made consciousness—that is, Christ—the best possible way to freedom: “For freedom, Christ has set us free. Stand firm, therefore, and do not submit again to a yoke of slavery” (Galatians 5:1).

Despite appearances, “freed for freedom” is not a pleonasm. Freeing oneself from the familiar is a good thing, but not an end in itself. It’s now fashionable to practice “letting go” in order to become free—but to what end? Paul answered this question: to become free for the sake of freedom! What is freedom? Proceeding from his direct view of Christ, Paul describes freedom in a way that was revolutionary for his time: “For though I am free with respect to all, I have made myself a slave to all, so that I might win more of them. To the Jews I became as a Jew, in order to win Jews. To those under the law I became as one under the law (though I myself am not under the law) so that I might win those under the law. To those outside the law I became as one outside the law (though I am not free from God’s law but am under Christ’s law) so that I might win those outside the law. To the weak I became weak, so that I might win the weak. I have become all things to all people, that I might by all means save some. I do it all for the sake of the gospel, so that I may share in its blessings.” (1 Corinthians 9:19–23)

Far from being a perverse, manipulative hypocrite, as he is often portrayed, Paul, like a forerunner, developed what Steiner later called the “sense of the ‘I’ of the other,” that is, an intimate understanding of otherness. Paul was far enough advanced along the path to the higher ‘I’ that he was able to perceive the—potential—‘I’ of those with whom he spoke; he was animated by a strong power of compassion. Freedom is still misunderstood in this Pauline sense today. Inseparably linked to the Christian impulse, freedom is at the heart of anthroposophy, which Steiner formulated as follows: “A moral misunderstanding, a clash is impossible with morally free human beings. . . . But, in the midst of coercive order, human beings, free spirits, rise up and find themselves in the mess of custom, legal compulsion, religious practice, and so on. . . . Nature makes of human beings merely natural beings; society makes them law-abiding beings; only they, themselves, can make themselves a free being.”13

To the Ephesians, Paul formulated with extraordinarily simplicity the context within which each individual can embed his or her work: “The pagans (nations) have become co-heirs, co-embodied, and co-participants in the promise in Christ Jesus through the gospel” (Ephesians 3:6, rev. by the author). This trilogy of togetherness contains a true temporal mystery. Sunklēronómos (co-heirs) means that human beings are united by inheritance, that is, by a common past. Sússōmos (co-embodied) says that human beings participate in a single body, in this case, the body of Christ as a social body. Therefore, they are united in the present. Summétokhos (co-participants) says that human beings are united by their deeds (metékhō, to participate in), which lead them into the future. In short, human beings are united through the past, the present, and the future in Christ, that is, in consciousness. Steiner [wrote in the days following on from] the Christmas Conference in 1923 with a similar emphasis as Paul about the importance of individual work in the common work: “[The Anthroposophical Society] lives only through what is worked within it.”14 Likewise, the whole of humanity has the same origin in the past, is united in a present consciousness, and produces itself in the future through the collaboration of all human individuals who “participate in” this edification.

Through this sketch of Paul’s letters, we have glimpsed how his thinking actually forms an original philosophy of freedom for all humanity. We can then understand why Rudolf Steiner regarded Paul’s thinking as the basis of anthroposophy’s epistemology: “To place epistemology on a Pauline basis was the task of my two writings Truth and Knowledge and The Philosophy of Freedom. These two books place themselves within the great achievement of the Pauline comprehension of the human being in the western lands of the world.”15 Despite the two millennia that separate us from Paul, the first of the Christian authors, his spiritual strength can inspire, enlighten, and stimulate us in our individual search.

All New Testament quotations are from The New Oxford Annotated Bible [NOAB], revised 4th ed. (New York: Oxford University Press, 2001); revised by the author as noted.

Translation (from German to English) Joshua Kelberman

Translation (original French to German) Louis Defèche

English translation revised by the author

Footnotes

- This prefix appears in anthrôpos [the human being as human being], literally “the one who can look back with consciousness to his origins.”

- Rudolf Steiner, Anthroposophy and the Inner Life: An Esoteric Introduction, CW 234 (Forest Row, East Sussex: Rudolf Steiner Press, 2015), lecture in Dornach on January, 1924.

- Rudolf Steiner, The Christ Impulse and the Development of Ego-Consciousness, CW 116 (Forest Row, East Sussex: Rudolf Steiner Press, 2015), lecture in Berlin on May 8, 1910.

- σύνεσις (5 times): 1 Cor 1:19; Eph 3:4; Col 1:9, 2:2; 2 Tim 2:7.

- σῠνείδησῐς (24 times): Rom 2:15, 9:1, 13:5; 1 Cor 8:7, 10, 12, 10:25, 27, 28, 29; 2 Cor 1:12, 4:2, 5:11; 1 Tim 1:5, 19, 3:9, 4:2; 2 Tim 1:3; Tit 1:15; Heb 9:9, 14, 10:2, 22, 13:18.

- Rudolf Steiner, Building Stones for an Understanding of the Mystery of Golgotha: Human Life in a Cosmic Context, CW 175, (Forest Row, East Sussex: Rudolf Steiner Press, 2015), lecture in Berlin on February 20, 1917.

- Blasphemy was punishable by death. Paul was even stoned several times and left for dead.

- The text of Acts (8:1) uses the verb suneudokeō, “to think with fervor,” an allusion to the fanaticism of the young Pharisee, who was not yet called Paul, but Saul.

- There are [64] occurrences of the word ekklēsía (ἐκκλησία) in the letters.

- From kắlŭx, we have in English “calyx,” the part of the flower that surrounds and conceals the petals while the flower has not yet blossomed.

- Rudolf Steiner, Constitution of the School of Spiritual Science: An Introductory Guide, (Forest Row, East Sussex: Rudolf Steiner Press, 2013), selections from GA 37 and GA 260a, lecture in Dornach on January 30, 1924.

- Rudolf Steiner, Life between Death and Rebirth: The Active Connection between the Living and the Dead, CW 140, lecture in Hanover on Nov. 18, 1912.

- Rudolf Steiner, The Philosophy of Spiritual Activity: Fundamental Features of a Modern Worldview: Results of Soul Observation According to the Natural-scientific Method CW 4 (Tiburon, CA: Chadwick Library Press, 2020), ch. IX, “The idea of spiritual activity (freedom).”

- Rudolf Steiner, Die Konstitution der Allgemeinen Anthroposophischen Gesellschaft und der Freien Hochschule für Geisteswissenschaft [The Constitution of the General Anthroposophical Society and the Independent Institute of Higher Education for Spiritual Science], GA 260a (Dornach: Rudolf Steiner Verlag, 1987); first published as “Die freie Hochschule für Geisteswissenschaft” [The independent Institute of Higher Education for Spiritual Science] part 5, in Was in der Anthroposophischen Gesellschaft vorgeht: Nachrichten für deren Mitglieder [What is happening in the Anthroposophical Society: News for its Members] 1, no. 6 (Feb. 17, 1924): 22.

- See footnote 3.