Despite his blindness, the experience of light reported by Jacques Lusseyran opens up new perspectives on the nature of light. Lusseyran draws attention to the inner dimension of light and shows how much there is behind what he called the “economy of light.”

“The moment I lost my sight, I found the light within me unchanged. I didn’t need to remember what it was for my eyes anymore… it was there, in my mind and in my body. It was inscribed there in its entirety. The light was there, together with all visible forms, colors, and lines, with the same force that it has in the world of eyes, namely, to grow and to fade, to move… I emphasize that everything I encountered was immediately seen, not touched or heard; it emerged, taking on form and color on an inner screen. And this was without me doing anything to trigger the phenomenon. How could I have done anything, since I was only eight years old?”1

When Jacques Lusseyran was suddenly blinded in an accident, the light was not taken away but continued to illuminate him. “The light that I continued to see without my eyes was the same as before. But my position in relation to that light had changed: I was closer to its source.”2

This astounding testimony can inspire us to change our relationship with light. Since Isaac Newton, science has given itself the task of studying the light that exists outside of human beings in a mechanical way, as a phenomenon that occurs in space and time. This approach ignores the fact that, within the human being, light is also an experience of consciousness. “A dark foreboding,” “all clear,” “shedding light on something”: these expressions point to the close relationship between light and knowledge. Thinking and understanding have to do with clarity of soul.

We perceive light in two ways: from outside, through our eyes, and from inside, when we “see” something clearly. The physicist who measures the vibrational frequency of a color through refraction in a prism registers the outer light. The inner light is considered to be a subjective, and thus unreal, experience.

Inner Light

There’s another way to discover the presence of inner light: through the experience of a blind person regaining sight. Oliver Sacks, the famous British neurologist, described the case of a man named Virgil, who was blind since early childhood and who, at the age of 50, had thick cataracts removed from both lenses. After the operation, his eyes were in perfect condition, but contrary to expectations, he didn’t see the world around him. It was just a “fog” that he could understand only when he heard or touched what was in front of him. Oliver Sacks wrote: “When we open our eyes each morning, it is upon a world we have spent a lifetime learning to see. We are not given the world: we make our world through incessant experience, categorization, memory, reconnection.”3 We actually don’t see what appears in front of our eyes (the outer light), but only what we picture within, that is, what we illuminate through interpreting (the inner light) what is in front of us. What we call “seeing” is the encounter between the outer and the inner light.

When we look at this drawing (Fig. 1) and “see” a cube, part of this “cube” reaches our retina. The retina provides us with a physical, material picture, but we immediately interpret this visual sensation with ideas—of lines, angles, planes, depth, volume, etc.—which we add to this pure visual perception; so what we see is the result, the union of these two lights. This is not only the case when we look at a drawing but also when we look at a real cube or any object. To see a bird, we add the concept “bird” to the moving colors floating in the air. Even when we see a simple spot, we give it meaning by interpreting it as, well, a “spot.” Plato, who studied under Pythagoras, described this process very well. He explained how what he called the lantern of the eye plays as important a role in our vision as sunlight.4 When we see, the inner light combines with the outer light—like with like—and together, they form a single, homogeneous body of light. This idea is reflected in Goethe’s famous sentence introducing his Theory of Color: “Were the eye not sun-like, how could we behold the light?”5

Of course, there aren’t really two kinds of light, but only one. True light is neither external nor internal; rather, it’s both: it comes from outside and from within, as two sides of the same reality. The moment his physical eyes were taken from him, Jacques Lusseyran found the complete light again within himself. “I became blind and the sun turned around. She left her physical heaven, she leapt into me, she stayed there, she shined there. The plants followed her, the stones, the furniture, all forms and their pleasures—and even the gas lamps on the pavement. Everything is close. Everything is so much closer than with your eyes. Going blind is like changing your center. It’s as if you were thrown so deeply into yourself that this inner self is no longer yours, but grows, conquers space, brings it back to you, and then loosens it and makes it vibrate. And that’s the pulse of a new life.”6

Suprasensible Nature of Light

Many people are surprised by the fact that light is invisible. What we see around us is matter that has been illuminated. Light makes things visible; it allows us to see. But light itself remains suprasensible, invisible. We can observe this by directing a beam of light (for example, a flashlight) into a large, dark room emptied of any obstructions. The beam of light itself remains invisible. The white beam that we normally see coming out of a flashlight is only visible because there’s some kind of matter in its path (water vapor, dust, objects, etc.) If the air were perfectly clean, dry, and empty, everything would remain dark. The landscape that unfolds before our eyes consists of matter: earth, trees, animals… that all reflect sunlight. I see the blue or gray sky because there’s a layer of cloudy atmosphere of varying thickness between my eyes and the depths of outer space. Beyond the atmospheric layer, the sky appears completely black, even though it’s full of immense distances of light. As soon as a material object (the moon or another planet, a satellite, etc.) enters this space, it shines brightly. Everywhere my eyes see light, they see matter that is more or less illuminated. We could object that we can still see light when we look at a light source such as the sun, the pole star, a lamp, or a flame. Actually, even in this case, we still only see illuminated matter: superheated gases, a lightbulb’s metal filament, etc. Our physical eye, which is made of matter, only ever sees illuminated matter. The light itself is a suprasensible reality.

In outer nature, the active reality of light shows itself in the growth of plants. It’s the splendor of the sun that draws the plant into the cosmic periphery, weaving the living substances formed by photosynthesis and shaping them into the astounding diversity of plant forms—into the stems that reach for the sky, into the leaves, where light creates living substance out of water and carbon dioxide from the air, and finally into the flowers, where they burst forth in beautiful colors, scents, and geometric shapes. Without light, the plant withers and dies, unable to develop and shape its forms.

In the inner space of the human soul, light awakens consciousness. (This undoubtedly also applies to our animal siblings, even if their consciousness doesn’t really fully awaken to self-awareness.) In light, our consciousness feels at home. It can orient itself, connect consciously with things, and perceive their relationships. Light draws our attention and enables us to consciously encounter the world. It reveals what would otherwise remain hidden, closed in on itself. It unveils the world and brings it into appearance. Light itself isn’t visible precisely because it is that which brings things into visibility.

Of course, without an eye that sees, the universe would also be invisible. But, we could also say: In a world where nothing can be seen, no organ of sight would be formed! That which brings things to visibility is also that which brings forth the eye. Goethe expressed it unequivocally: “The eye owes its existence to light. From indifferent animal organs, light calls forth an organ that will be its equal, and so the eye forms itself through light, for light, thereby enabling inner light to encounter outer light.”7 Already in the embryo, in the darkness of the mother’s womb, the eye is formed by suprasensible light. Even before birth, the human being possesses a light that builds an organ for itself. After birth, when the newborn first opens their eyes, this inward, suprasensible light encounters the outward light that actively weaves life in space. It’s a significant phenomenon that a newborn learns to fix their gaze by first meeting the gaze of another human being, usually their mother. When the two gazes, the two lights, touch, something visible arises. Since our eye is built according to the laws of light and it can produce colors according to the laws that are effective in the world, we can see the colors of the world with its help. How could it be otherwise than that the sense organs are the result of the world’s effects within us?

Thought Light

In a lecture from 1922, Rudolf Steiner described the phenomenon of light as follows: “The human being is born out of light, and his inwardness, the inwardness of his head, is the result of light. The entire nervous system is, indeed, the result of light. Light is not only transmitted through the eye, but also through the other senses. The eye is only the sense organ that transmits light in a primary way. We cannot say that blind human beings are completely cut off from light. The light works in them; it’s only their conscious perception of light that’s gone.”8 The “conscious perception of light” is the perception of light reflected by matter. Indeed, our ordinary consciousness must rely upon matter to sustain itself: the matter of the brain and the nervous system and the matter of external objects.

Helen Keller’s testimony is particularly interesting. Blind, deaf, and mute since she was one year old, she described an experience she had at seven, before which she’d lived wholly withdrawn into herself, uttering wild cries, and on the brink of madness: “Some one was drawing water and my teacher placed my hand under the spout. As the cool stream gushed over one hand she spelled into the other the word ‘water,’ first slowly, then rapidly. I stood still, my whole attention fixed upon the motions of her fingers. Suddenly I felt a misty consciousness as of something forgotten—a thrill of returning thought; and somehow the mystery of language was revealed to me. I knew then that ‘w-a-t-e-r’ meant the wonderful cool something that was flowing over my hand. That living word awakened my soul, gave it light, hope, joy, set it free.”9 Like Jacques Lusseyran, Helen Keller studied at a university and went on to write several books.

The word “water” led little Helen to the concept, to the thought of “water.” And this thought enlightened her, liberated her, and filled her with joy. Light has the property of allowing us to participate in that which is outside of us. Quietly and actively, light weaves between things, bringing the different parts together and unifying them. Jacques Lusseyran also made the connection between light and joy: “I discovered light and joy at the same time.”10 It was this true and indestructible joy that enabled him, as we know, to survive the terrible trials of the death camps a few years later while many around him died of despair.

Like light, thought also becomes conscious by attaching itself to matter. As long as my brain is functioning properly, it gives me thoughts. But they are past thoughts, learned thoughts, already known, frozen, and dead, and the connections between my neurons are established automatically. Jacques Lusseyran and Helen Keller show us the way to the true, immaterial, creative, living light: the light that created the eye, the brain, the tree, and the world. The light of the world. This light has a source, and that is the living, new thinking that no longer relies on the preformed circuits of the brain but on the light of living concepts that are always new because they are newly created in the present, in the pure clarity of understanding: “Ah, I ‘see’ what you mean!” We can activate this thinking in us, which draws directly from the light of the living spirit. This is no longer an intellectual activity having to do with formal, learned concepts expressed in empty words, but rather a voluntary, new activity: the purely individual activity of the living spirit in each of us.

Metamorphosis of the Soul

To summarize, with our physical senses, we see the reflection of light on external matter. We receive this reflection of light naturally from our sense organs without us having to do anything other than keep them in good condition. We don’t easily see the inner light that lives in our thoughts; this light that freezes more and more in our brain connections and preconceived ideas as we learn. “There was only one way,” says Jacques Lusseyran, “to see the inner light: to love.”11He found that the inner light does not always shine. When he was sad, when he was afraid, when he gave in to anger or hatred, everything went dark and disappeared. When he was happy and attentive, all the pictures became bright.12

The effort to grasp the light within oneself through clear thinking brings about a metamorphosis in the soul (and, fortunately, we need not lose our physical eyes to be able to realize this). Similar to a magnifying glass that concentrates light at its focal point, living thinking becomes a fire and ignites the will. Focused through the ‘I,’ the light shines as a moral ideal and ignites our power of initiative. An idea freely generated by the ‘I,’ without any other reason to act except love for the deed itself, will not remain passive: it joyfully “wills” to be realized through me. In this moment, I act out of moral “understanding,” because I comprehend and perceive the meaning of this action within the order of the world, within the evolution and becoming of the world. Jacques Lusseyran’s “economy of light” is what will enable humanity to move forward in the growing darkness, as more and more human beings discover it within themselves and bring it to realization in social life.

Translation from French to German Louis Defèche

Translation from German to English Joshua Kelberman

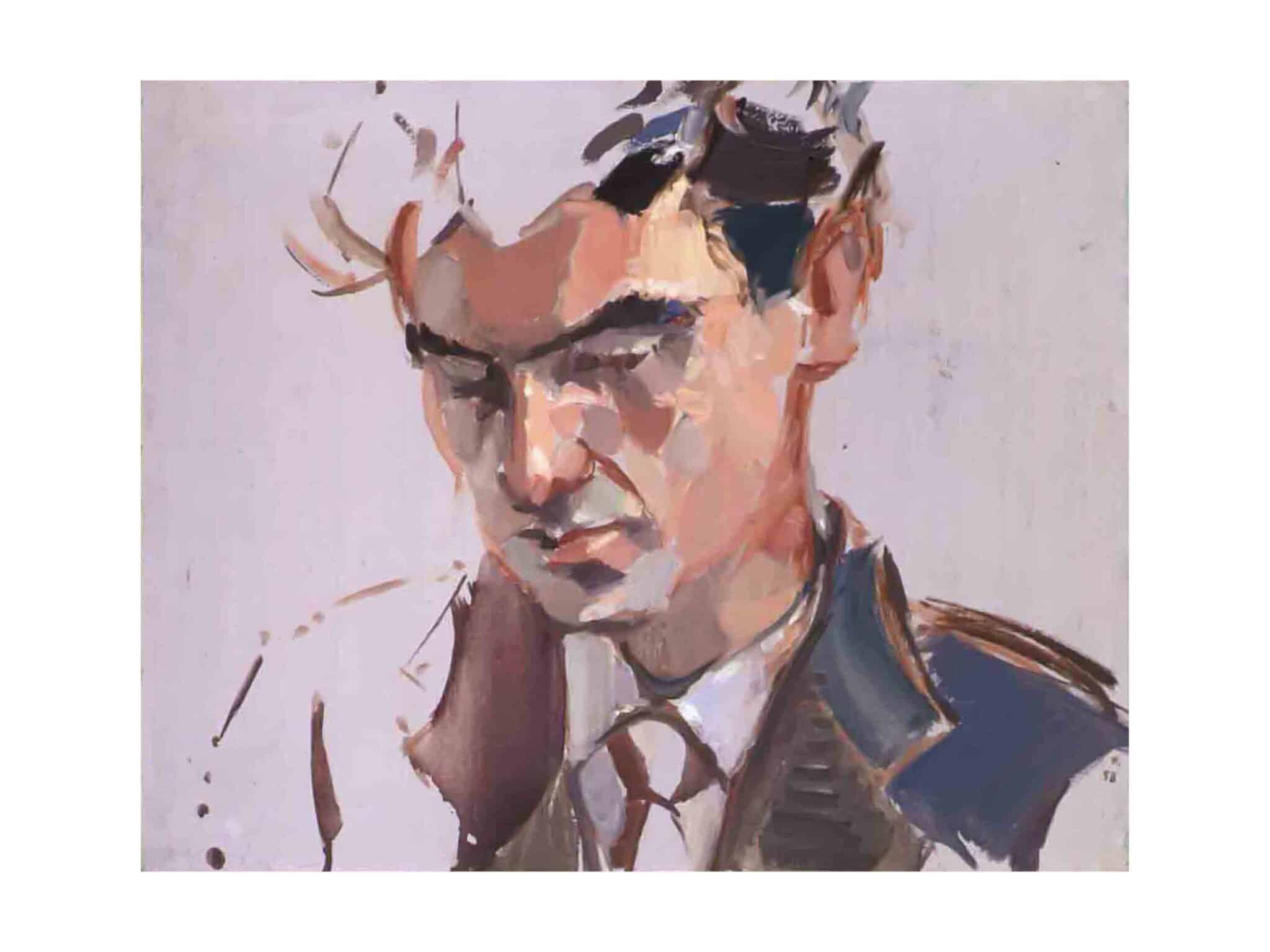

Title image Jean Hélion, “Jacques Lusseyran,” 1958. Private collection, ©2024, ProLitteris, Zürich.

Footnotes

- Jacques Lusseyran, “Un nouveau regard sur le monde,” [A new way of looking at the world] in: La lumière dans les ténèbres [Light in the darkness] (Paris: Éditions Triades, 2002); [cf. “Blindness, a New Seeing of the World,” in Against the Pollution of the I: Selected Writings of Jacques Lusseyran (New York: Parabola, 1999).]

- Ibid.

- Oliver Sacks, An Anthropologist on Mars: Seven Paradoxical Tales (New York: Vintage, 1995), ch. “To See and Not See.”

- Plato, Timaeus.

- Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Theory of Color (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1970).

- Jacques Lusseyran, Conversation amoureuse (Fair Oaks, CA: Rudolf Steiner College, 2018); first published in French in 1990.

- See footnote 5.

- Rudolf Steiner, The Sun Mystery and the Mystery of Death and Resurrection: Exoteric and Esoteric Christianity, CW 211 (Great Barrington, MA: SteinerBooks, 2006).

- Helen Keller, The Story of My Life (New York: Penguin, 2010); first published 1903.

- Jacques Lusseyran, And There Was Light (Edinburgh, UK: Floris, 1985); first published in French in 1953.

- Jacques Lusseyran, “L’aveugle dans la société,” in La lumière dans les ténèbres [Light in the darkness] (Paris: Éditions Triades, 2002); [cf. “The Blind in Society,” in Against the Pollution of the I: Selected Writings of Jacques Lusseyran (New York: Parabola, 1999).]

- Ibid.