A review of the play Fire in the Temple, performed in the USA.

The year 2023 marked a significant step in anthroposophical history: for the first time, Rudolf Steiner has been portrayed in a mainstream movie. The film is Lasse Hallstrom’s production of Hilma, based on the life of the Swedish painter Hilma af Klint, an artist who felt deeply connected to Steiner. Although actor Tom Wlaschiha’s blue eyes and dapper suits detract from the historical accuracy of his rendering, it is nonetheless astonishing to see any version of Rudolf Steiner (and, for a moment, even the First Goetheanum) on the big screen.

Concurrently, and perhaps by way of an antidote, the year also witnessed the portrayal of Rudolf Steiner on the stage in the new drama, The Fire in the Temple, written by Glen Williamson and directed by John McManus. In September, the play had seven premiere performances in Harlemville, NY, Chestnut Ridge, NY, and Kimberton, PA. It was the final step of six years of collaborative work involving the writer, director, and the community of actors, speech artists, and eurythmists who had presented dramatic readings and previews to small audiences.

The play spans the months beginning New Year’s Eve, 1923, when the First Goetheanum was destroyed by arson, through March of 1925, when Rudolf Steiner died, possibly as the result of poisoning. Although reference is often made to the stormy events transpiring in Europe that were to alter the course of world history, the play’s focus is on the interplay of Rudolf Steiner and his wife, Marie Steiner, his physician, Ita Wegman, and his colleagues, Günther Wachsmuth and Ehrenfried Pfeiffer. Like the Three Graces, the sculptor Edith Maryon, the astronomer Elisabeth Vreede, and the eurythmist “Fraulein Samwaller” (a composite figure based on several people, particularly Mieta Waller) play smaller but no less significant roles. In the spirit of parte repraesentans totem, even these spiritually attuned relationships have more than their share of turbulence.

Those years of “anthroposophical history,” so filled with remarkable achievement in the face of ineluctable tragedy, would in themselves present a challenge to a dramatic depiction. In the spirit of Steiner’s Mystery Dramas, Williamson also expands the audience’s vistas by millennia as we witness the karma that is being played out at significant junctures on the stage. This is a daunting task for a stage play: even the skilled cinematic skills of the Wakowskis in their film The Cloud Atlas were profoundly challenged when trying to bring reincarnation to the screen.

Williamson’s script guides his audience in “breathing in Time,” allowing for an experience of contraction in the present life and expansion into past lives. The play’s director, John McManus, developed a simple but powerful means to represent successive incarnations onstage, eschewing special effects and providing the audience with a dynamic “shuffling off of the mortal coil” as characters flow from one incarnation to another. Audience members may have found themselves initially confused as Ita Wegman merged into the being of Alexander the Great or Albertus Magnus transformed into Marie Steiner. However, this proved to be a brilliant directorial approach, for the characters on stage were themselves no less confused as they experienced their past incarnations. The audience could vicariously share in the awakening of the joys, sorrows, and profound responsibilities inherent in crossing the threshold of self-knowledge.

It is only natural to assume that a play in which Rudolf Steiner is the protagonist would verge on hagiography, but that is not the case. Williamson walks the fine line between Steiner the Initiate and Steiner the human being—even the playful human being who delights in engaging in a silly game with one of his proteges. Indeed, that fine line between the man and his mission is the play’s “open secret” and the mainspring of its most compelling drama.

As Ita Wegman’s consciousness expands, Steiner tells her: “The old mysteries are fading. But new mysteries can now be built on karmic relationships. . . It would be good if more people could wake up to these connections—and also grasp their own karmic threads.” That these relationships can only be brought to resolution and harmony by human beings incarnated in physical bodies was a revelation often overlooked by those closest to Steiner. Cataclysmic as the burning of the Goetheanum was, as the play proceeds, that tragedy fades into the background. The greater tragedy, we realize, is that those nearest to Steiner fell short of recognizing their connectedness—not only to their teacher but to one another. We might imagine that coming to experience past lives and karmic relationships would open new vistas of social harmony, but that is not a given. Indeed, on the stage, such revelations may merely provide more fuel for the competitive fire blazing in repartee that is tragicomic in its intensity. Williamson portrays highly developed individuals like Günther Wachsmuth and Marie Steiner expressing their corrosive jealousy not only toward the present-day Ita Wegman, but toward her past identities as well.

Approaching the Goetheanum’s ruins, Steiner insists, “In spiritual work, there is no failure, only diversion and delay. We will build again,” and so the monumental task of erecting the Second Goetheanum begins. Given his respect for the freedom of others, Steiner could not command the transformation of his associates’ sympathies and antipathies towards one another—those fires would not be quenched so easily. It is ironic that even though his colleagues keep close watch over one another’s interactions with their teacher, their rivalries blind them to the appearance of a figure at a public gathering who slips poison into Steiner’s tea.

The progressive forces helping the anthroposophical impulse are portrayed through the eurythmic movements of the Archangel Michael, and the oppositional forces are represented as “Green Demons” who slither on and off the stage at critical moments. The fact that the demons are performed by the same actors who portray Wachsmuth, Pfeiffer, Maryon, and others makes it possible to stage this ambitious play with a small cast. But John McManus’ staging of these demonic appearances also makes it clear that the demons are not the cause of the hindrances and errors that are underway but are rather the effects of the human beings’ unconscious decisions and actions.

The play begins, as the title promises, with the luciferic conflagration of the Goetheanum fire, but it concludes on a colder and more ahrimanic note. In Robert Frost’s words,

Some say the world will end in fire,

Some say in ice . . .

. . . But if it had to perish twice,

I think I know enough of hate

To say that for destruction ice

Is also great

And would suffice.

Williamson does not hesitate to indicate that the external attacks on Steiner and his teachings—even those staged by a powerful and reactionary Brotherhood—were not the greatest obstacles that he faced. Steiner understood it was the all-too-human failings of those nearest and dearest to him that sapped his vital forces and were to have a calamitous effect on the future of the movement he founded. As Steiner crosses the Threshold at the play’s conclusion, it appears likely that the rivalries will continue. Fire in the Temple concludes with the gathering of human and spiritual beings around Steiner’s deathbed. It is a scene filled with despair, Michaelic resolve—and ambivalence.

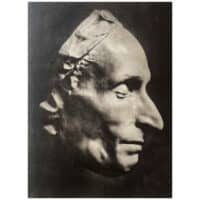

The collaborative energies of the playwright and director created a unique and powerful production. The performances of the principals, Rudolf Steiner (Peter Josephson), Ita Wegman (Rosibel Mejia), and Marie Steiner (Laurie Portocarrero), were incandescent. The coruscating sparks that fly between the independent spirits of Steiner and his wife seem born from flint and steel, while the light that flows between Steiner and Ita Wegman is enveloped by the warmth of karmic recognition. In the production of the play that I saw in Camphill Village Kimberton Hills, every actor delivered an exceptional performance. Peter Josephson’s Rudolf Steiner, in particular, was not only a portrayal. Onstage for most of the play’s two and a half hours, he seemed at times to embody Steiner; even as he lay upon his deathbed, his life forces ebbing, Josephson’s dramatic energy was tangible.

For anyone connected with a community or institution based on Rudolf Steiner’s initiatives, Fire in the Temple may serve as a vivid and moving re-introduction to the man and his work and the urgency of his teachings about karma. And for those who are avid readers of Steiner’s books and lectures but are less familiar with the people close to him at the end of his life, this play may be a reminder of the enormous challenges and obstacles Steiner faced before his death. As a documentary, a comedy of manners, a tragedy, and a Mystery Drama woven into one, Fire in the Temple stands as a unique contemplation of the centrality of Rudolf Steiner in our time. It deserves many more performances.

Performances Rudolf Steiner – Peter Josephson, Marie Steiner – Laurie Portocarrero, Ita Wegman – Rosibel Mejia, Fräulein Samwaller, “Sam” – Kayla Hope Nicosia, Edith Maryon – Faith DiVecchio, Ehrenfried Pfeiffer – Liam McGilligan, Günther Wachsmuth – Dhruva Corrigan, Elisabeth Vreede – Catherine Decker, Secret Brother – Marke Levene, Grand Master – Vincent Roppolo, Archangel Micha-el – Zachary Dolphin

More Fire in the Temple

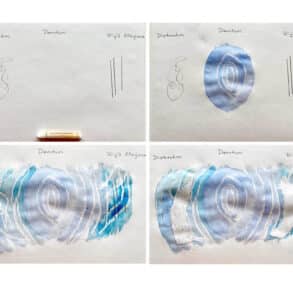

Image Final scene from Fire in the Temple, Photo: Catdodge Photography, Source: Anthropos

How can this play become a film and available online for those of us in the rest of the world?

What support does it need?

It would be such a gift.

Dear Elaine,

Please excuse this late response to your comment. I certainly agree with your wish to make this remarkable play available to the widest possible audience! Glen, the producer and playwright, and John, the director, are focused right now on arranging for more live performances. However, I just wrote to Glen and urged him to recognize the exponentially greater audience that a filmed version could reach. I asked if I could send you his email address and he agreed. I am sure that you and he will have a helpful conversation: glenwill@mail.com With best wishes, Eugene Schwartz