From a certain perspective, dying is the best way to deal with life. Our life is only perfect when we also acquaint ourselves with death; it’s really best to make friends with death. Imagine for a moment that a human life was endless. Never dying—that would be the worst thing that could happen to us. Real life would then no longer be possible. It would just be a kind of vegetation.

When a life comes to a natural end, death is often a salvation. When someone becomes weak and frail, when the burden of years and cares can no longer be borne, death comes as a savior. It then allows for a different kind of life to be possible. “Life is nature’s most beautiful invention and death is her artifice to have more life.”1 From time to time, we can see a visible sign of “greater life”—even a sign of redemption—as an imprint in the mortal body. Following the struggle of death, sometimes, we see an expression of sublime calm and peace on the deceased’s face: death as redeemer.

Have we ever realized that death was not a savior for Christ? On the contrary! After his death, he had to fulfill the most difficult task that exists on Earth. He, himself, had to redeem death! With his death on the cross, his mission on Earth was not yet fulfilled. Long before this, Christ had already announced his greatest task with the words: “Three days and three nights the Son of Man will be in the heart of the Earth” (Matthew 12:40). The heart of the Earth: this is the realm of death and the underworld (Greek: Thanatos and Hades, Revelation 1:18).2 Christ did not wage the greatest battle on Earth, but rather in the heart of the Earth, in order to overcome death and the underworld from within. Since his death and his resurrection, every human being who seeks him and follows him can experience death in a different way than before—no longer as a prisoner in the heart of the Earth but now carried in the heart of Christ. Thanks to his death, death is no longer our enemy. He can even help us to find Christ: In Christo morimur [In Christ, we die]. One cannot start practicing the art of dying early enough—even if it is only “hand exercises” at first. That’s why the children who stand in front of the altar in the Christian community hear again and again that the Spirit of God leads life into death and that which is dead into life. Thus, they learn to know the spirit.

Christ’s body was not just placed into the Earth. He, himself, joined himself to the Earth like a seed—in order to bear fruit for the whole world.

“I Will Not Send You Off”

Illness is something that affects every human being at some moment in their lives. Friedrich Rittelmeyer once wrote an essay entitled: “For the Sick and Those Who Could Become So.”3 Naturally, there will come a time when each of us will have to deal with it. None of us are comfortable with the thought of becoming dependent on other human beings. And even more worrying is the idea of no longer being able to stand on our own two feet and becoming bedridden. In such helplessness, it is the greatest test not to become impatient or rebellious. A sick person is also called a “patient,” from the Latin patientia, patience. This is an indispensable prerequisite for recovery! As a patient, it’s better we don’t ask ourselves “Why me? What am I being punished for?” Such questions are no help for recovery; just the opposite is the case. Instead of looking back and tormenting ourselves with such questions that we can’t answer, it’s more productive to look ahead and ask ourselves: “What can I develop through this illness? Is there perhaps a hidden gift in this trial?” Novalis writes: “Illnesses, especially protracted ones, are apprenticeships in the art of living and character building.”4 He knew what he was talking about, having been tested by illness for years.

Imagine that behind every illness, there is an angel waiting to share a precious gift with us. Like Jacob, who fought an invisible enemy at night, we can say to him: “I will not send you off unless you bless me.” [Gen. 32:26]

Since Christ lived upon the Earth, every illness can become a path to salvation—as long as we become real “patients” who walk the narrow path through the eye of the needle with patience. Just as he did during his life upon the Earth, he can say to each of us: “This sickness is not unto death but for the glory of God” (John 11:4).

Translation Joshua Kelberman

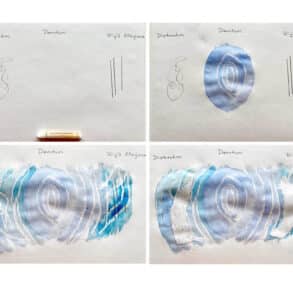

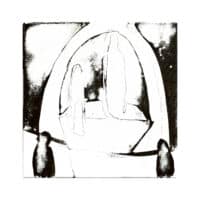

Image Christina Deravedisian

Footnotes

- From “Fragment über die Natur” [Fragment on Nature], Tiefurter Journal, no. 32 (1782/83). The authorship is contested. Rudolf Steiner considered Goethe to have spoken the content to Johann Georg Christoph Tobler (1757–1812, Swiss theologian), who subsequently wrote it down from memory with great accuracy, and, today, is largely considered the author of the text; cf. Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Scientific Writings, ed. Douglas Miller (New York: Suhrkamp, 1988); Rudolf Steiner, What is Necessary in these Urgent Times, CW 196 (Great Barrington, MA: SteinerBooks, 2010), lecture in Dornach, Feb. 1, 1920; Rudolf Steiner, “Zu dem ‘Fragment’ über die Natur” [On the “Fragment” about Nature], Methodische Grundlagen der Anthroposophie 1884–1901: Gesammelte Aufsätze zur Philosophie, Naturwissenschaft, Ästhetik und Seelenkunde [Methodical Foundations of Anthroposophy 1884–1901: Collected Essays on Philosophy, Natural Science, Aesthetics, and Science of the Soul], GA 30 (Dornach: Rudolf Steiner Verlag, 1989), originally published in Schriften der Goethe-Gesellschaft, vol. 7 (Weimar: Goethe’s Gesellschaft, 1892)—Tr. note.

- “I AM The First and The Last, and The Living One, and Ceased to Be Dead; and, Behold, I am living into the eternity of eternity, and have the keys of Death (Thanatos) and the Underworld (Hades)” (Rev. 1:17–18)—Tr. note.

- Friedrich Rittelmeyer, “Für Kranke und die, die es werden können” [For the Sick and those, who could become so], Die Christengemeinschaft [The Christian Community] 27 (1955).

- Novalis, Fragmente [Fragments], edited by E. Kamnitzer (Dresden: Wolfgang Jess, 1929).

Your articles, are very promising! One can’t help but think, however: if only one—who has so many expenses, and cannot afford to add more of then—could be allowed to even finish reading articles; without being cut off by the offers to subscribe! Understanding of this situation, in these world financial, and difficult conditions, would be a real blessing! (and even those who have tight financial situations, can be contributors to this forum!). Thank you for this opportunity to comment!

Thank you so much for your interest in our articles! At the Wochenschrift/Goetheanum Weekly, we rely entirely on our generous subscribers and adverstisers to be able to bring these offerings every week, so we are very grateful for your support. We can’t do it without you! Warm regards